Endometriosis is a common multifocal gynecologic disease that manifests during the reproductive years, often causing chronic pelvic pain and infertility. It may occur as invasive peritoneal fibrotic nodules and adhesions or as ovarian cysts with hemorrhagic content. Although the findings at the physical examination may be suggestive, imaging is necessary for the definitive diagnosis, patient counseling and treatment planning. The imaging techniques that are most useful for preoperative disease mapping are transvaginal ultrasonography (US) after bowel preparation and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Materials and method. In our retrospective study, associations of MRI diagnoses versus intraoperative diagnoses are statistically significant, with high specificity on rectal lesions (96.8%), respectively 96.2% on sigmoid lesions, then parametrial lesions and rectovaginal septum lesions. The dimensions of the rectal nodules had a nonparametric distribution (p<0.05) and the dimensions of the sigmoid nodules had a normal distribution (p>0.05) according to the Shapiro-Wilk test. Despite some limitations, magnetic resonance imaging is able to directly demonstrate deep pelvic endometriosis. The MRI features depend on the type of lesions: infiltrating small implants, solid deep lesions mainly located in the posterior cul-de-sac and involving the uterosacral ligaments and torus uterinus, or visceral endometriosis involving the bladder and rectal wall.

IRM – avantaje şi limite în diagnosticul şi tratamentul endometriozei

MRI – advantages and limitations in the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis

First published: 15 aprilie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Gine.32.2.2021.5004

Abstract

Rezumat

Endometrioza este o boală ginecologică multifocală comună, care se manifestă în timpul anilor de reproducere, cauzând adesea dureri pelviene cronice şi infertilitate. Poate apărea ca noduli şi aderenţe fibrotice peritoneale invazive sau ca chisturi ovariene cu conţinut hemoragic. Deşi constatările la examenul fizic pot fi sugestive, imagistica este necesară pentru diagnosticul definitiv, consilierea pacientei şi planificarea tratamentului. Tehnicile imagistice care sunt cele mai utile pentru cartografierea preoperatorie a patologiei sunt ultrasonografia transvaginală (SUA) după pregătirea intestinului şi imagistica prin rezonanţă magnetică (IMR). Materiale şi metodă. În studiul nostru retrospectiv, asocierile diagnosticelor IRM cu cele intraoperatorii sunt semnificative statistic, cu specificitate ridicată în cazul leziunilor rectale (96,8%), respectiv 96,2% pentru leziunile sigmoide, apoi leziunile parametriale şi leziunile septului rectovaginal. Dimensiunile nodulilor rectali au avut o distribuţie nonparametrică (p<0,05), iar dimensiunile nodulilor sigmoizi au avut o distribuţie normală (p>0,05), conform testului Shapiro-Wilk. În ciuda unor limitări, imagistica prin rezonanţă magnetică este capabilă să demonstreze în mod direct endometrioza pelviană profundă. Caracteristicile imagistice ale rezonanţei magnetice depind de tipul leziunilor: infiltrarea implanturilor mici, leziuni profunde solide localizate în principal în sacul posterior şi care implică ligamentele uterosacrale şi torusul uterin sau endometrioza viscerală care implică vezica şi peretele rectal.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a common multifocal gynecologic disease that manifests during the reproductive years, often causing chronic pelvic pain and infertility(1), defined as adenomyosis externa, mostly presents as a single nodule, larger than 1 cm in diameter, in the vesicouterine fold or close to the lower 20 cm of the bowel. When diagnosed, most nodules are no longer progressive. In more than 95% of cases, deep endometriosis is associated with very severe pain. It may occur as invasive peritoneal fibrotic nodules and adhesions or as ovarian cysts with hemorrhagic content. Although the findings at physical examination may be suggestive, imaging is necessary for the definitive diagnosis, patient counseling and treatment planning. The imaging techniques that are most useful for preoperative disease mapping are transvaginal ultrasonography (US) after bowel preparation and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

MRI is indicated as a complementary examination in complex cases of endometriosis with extensive adhesions and ureteral involvement(2).

Endometriosis may also manifest as multiple, homogeneously hyperintense cysts on T1-weighted images. The involvement of the alimentary tract or bladder can appear as areas of high signal intensity. Although magnetic resonance imaging is limited in its ability to depict small endometrial implants and adhesions, the advantages of MRI over laparoscopy include the ability to characterize endometriotic lesions and to evaluate extraperitoneal sites of involvement, contents of a pelvic mass, or lesions hidden by dense adhesions. The roles of the two modalities are therefore complementary. The knowledge of the variety of magnetic resonance imaging appearances of endometriosis and of the organ involvement within the pelvis is important for guiding a subsequent laparoscopic examination(3).

Deep pelvic endometriosis is defined as subperitoneal infiltration of endometrial implants in the uterosacral ligaments, rectum, rectovaginal septum, vagina or bladder(1).

Materials and method

We conducted a retrospective study between 2017 and 2021 on a group of 99 patients, aged between 25 and 50 years old, operated in the “Prof. Dr. Panait Sîrbu” Clinical Hospital of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Euroclinic Hospital – Private Health Network, and Monza Hospital, Bucharest.

Exclusion criteria:

-

patients who did not perform the MRI investigation;

-

patients in whom intraoperative data were missing.

Statistical analysis and results

The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 and Microsoft Office Excel/Word 2013. The quantitative variables were tested for distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test and were expressed as means with standard deviations or medians with interpercentile intervals. The categorical variables were expressed in absolute or percentage form and were tested using Fisher’s Exact Test.

The existing correlations were made using the Pearson correlation coefficient, respectively Spearman’s rho, depending on the distribution of the quantitative variables.

The data in Table 1 represent the characteristics of the studied group. The following are observed:

-

The average age was 32.66 ± 5.52 years old, with a median of 33 years old.

-

The most common age category was 30-39 years old (65.3%).

-

2020 (38.4%) and 2019 (37.4%) were the years in which most patients were included.

-

Most patients came from Monza (58.6%) or Giuleşti (32.3%).

-

Most patients had changes observed at the clinical examination (83.8%).

-

The mean value of preoperative AMH was 1.803 ± 2.833 ng/mL, with a median of 0.665 ng/mL.

-

The average total AFS-R score was 3.46 ± 0.747 points, with a median of 4 points.

-

Most patients had no complications (99%); only one patient had postoperative complications (postoperative fever).

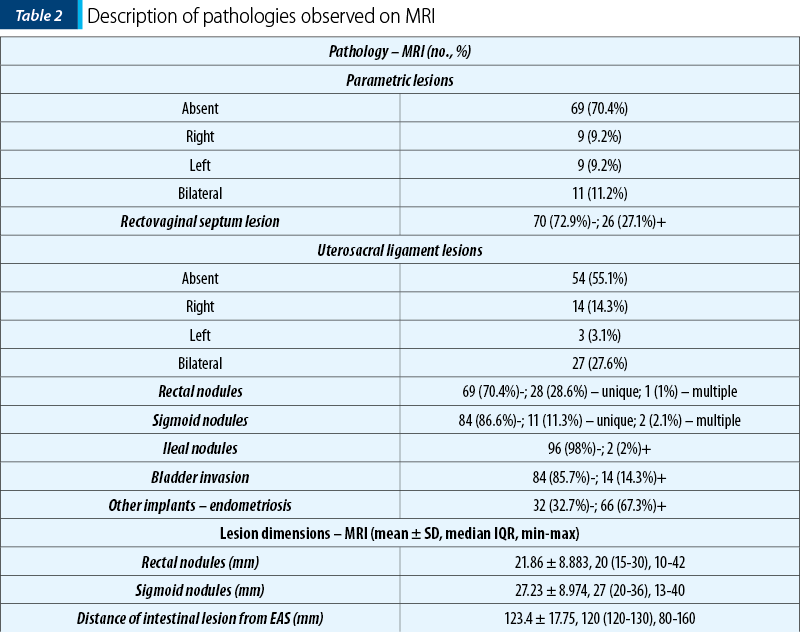

The data in Table 2 represent the description of the pathologies observed on MRI. The following are observed:

-

29.6% of the patients had parametric lesions, more frequently bilateral (11.2%).

-

27.1% of the patients had lesions of the rectovaginal septum.

-

44.9% of the patients had uterosacral ligament lesions, more frequently bilateral (27.6%).

-

29.6% of the patients had rectal nodules, more frequently unique (28.6%).

-

13.4% of the patients had sigmoid nodules, more frequently unique (11.3%).

-

2% of the patients had ileal nodules.

-

14.3% of the patients had bladder invasion.

-

67.3% of the patients had other locations of endometriosis.

-

The average size of the rectal nodules was 21.86 ± 8.883 mm, with a median of 20 mm.

-

The average size of the sigmoid nodules was 27.23 ± 8,974 mm, with a median of 27 mm.

-

The mean distance of intestinal lesions from the external anal sphincter was 123.4 ± 17.75 mm, with a median of 120 mm.

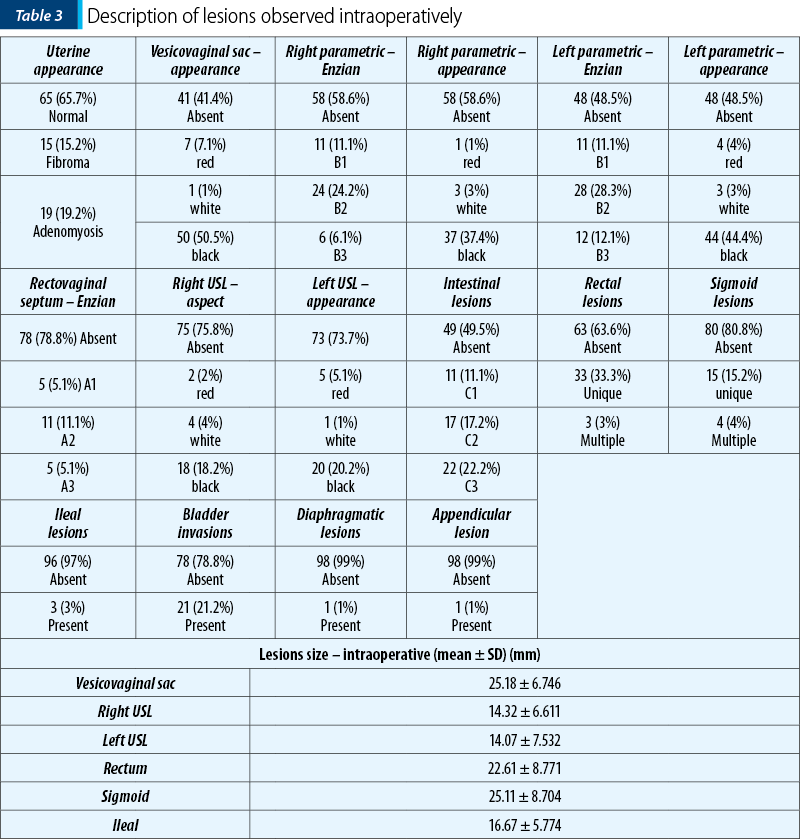

The data in Table 3 represent the description of the pathologies observed intraoperatively. The following are observed:

-

Most patients had a normal appearance of the uterus (65.7%), 15.2% of the patients had fibroids and 19.2% of the patients had adenomyosis.

-

58.6% of the patients had anterior sac lesions, more frequently with a black appearance (50.5%), with an average size of 25.18 ± 6.746 mm.

-

41.4% of the patients had right parametric appearance, 37.4% with black appearance, and 51.5% of the patients had left parametric lesions, more frequently class B2 (28.3%) and with black appearance (44.4%); 24.2% of the patients had straight parametric lesions, more frequently class B2.

-

21.2% of the patients had lesions of the rectovaginal septum, more frequently class A2 (11.1%).

-

24.2% of the patients had right USL lesions, more frequently with a black appearance (18.2%) and with an average size of 14.32 ± 6.611 mm, and 26.3% of the patients had left USL lesions, more frequently with a black appearance (20.2%) and with an average size of 14.07 ± 7.532 mm.

-

50.5% of the patients had intestinal lesions, more frequently class C3 (22.2%), 36.4% had rectal lesions, more frequently single (33.3%), with an average size of 22.61 ± 8.771 mm, 19.2% had sigmoid lesions, more frequently single (15.2%), with an average size of 25.11 ± 8.704 mm, and 3% of the patients had ileal lesions, with an average size of 16.67 ± 5.774 mm;

-

21.2% of the patients had bladder invasion and 1% of the patients had diaphragmatic or appendicular invasion.

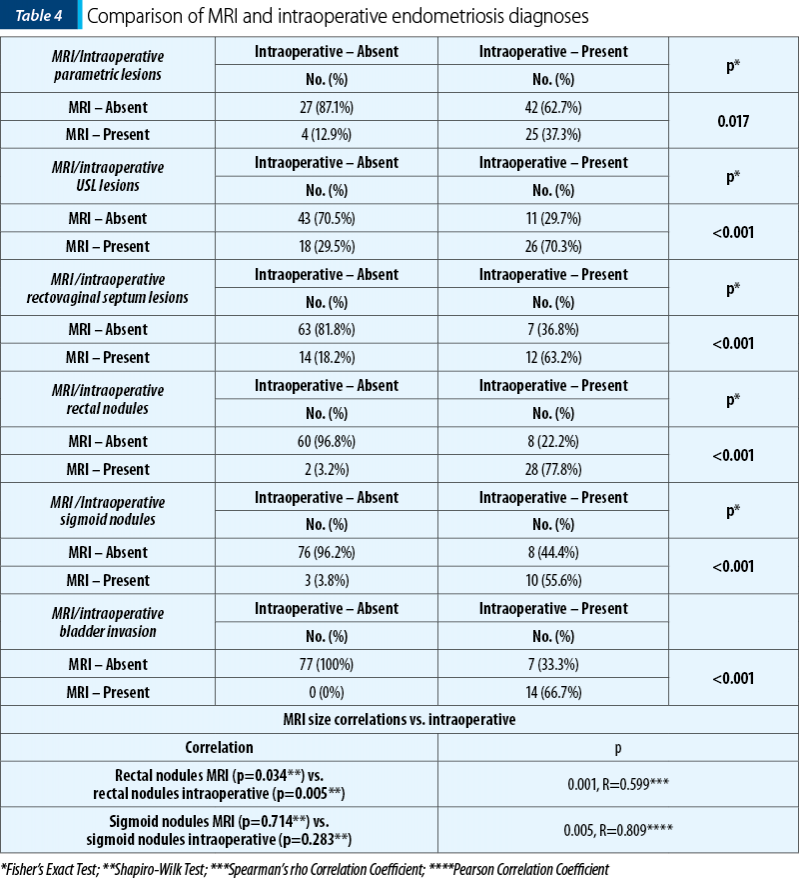

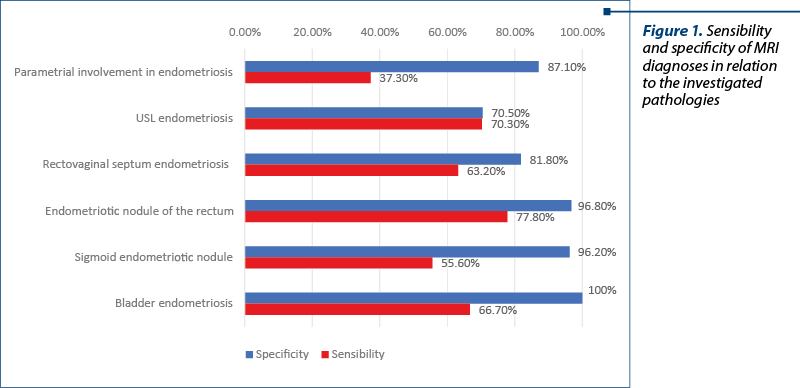

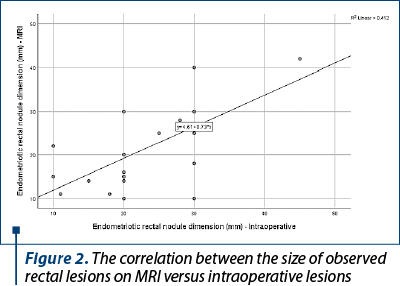

The data from Table 4 and Figures 1-3 represent the comparison between MRI and intraoperative endometriosis diagnoses. The results show that:

The Associations of MRI diagnoses versus intraoperatively are statistically significant, according to Fisher tests (p<0.05), noting that:

-

In the case of parametric lesions, the specificity was 87.1% and the sensitivity was 37.3%.

-

In the case of USL lesions, the specificity was 70.5% and the sensitivity was 70.3%.

-

In the case of rectovaginal septal lesions, the specificity was 81.8% and the sensitivity was 63.2%.

-

In the case of rectal nodules, the specificity was 96.8% and the sensitivity was 77.8%.

-

In the case of sigmoid nodules, the specificity was 96.2% and the sensitivity was 55.6%.

-

In the case of bladder invasion, the specificity was 100% and the sensitivity was 66.7%.

The dimensions of the rectal nodules had a nonparametric distribution (p<0.05) and the dimensions of the sigmoid nodules had a normal distribution (p>0.05) according to the Shapiro-Wilk test.

The correlation between the dimensions of the observed rectal nodules MRI versus intraoperatively is significant and of high degree (p=0.001, R=0.599).

The correlation between the dimensions of the sigmoid nodules observed by MRI versus intraoperatively is significant and of very high degree (p=0.005, R=0.809), the similarity between dimensions being much higher.

Discussion

An accurate preoperative assessment of disease extension is required for planning the complete surgical excision, but such assessment is difficult with physical examination. Various sonographic approaches (transvaginal, transrectal, endoscopic transrectal) have been used for this purpose, but they do not allow a panoramic evaluation. Furthermore, exploratory laparoscopy has limitations in demonstrating deep endometriotic lesions hidden by adhesions or located in the subperitoneal space.

Solid deep lesions have low to intermediate signal intensity with punctate regions of high signal intensity on T1-weighted images, show uniform low signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and can demonstrate enhancement on contrast-enhanced images. Magnetic resonance imaging is a useful tool. The MR imaging features depend on the type of lesions: infiltrating small implants, solid deep lesions mainly located in the posterior cul-de-sac and involving the uterosacral ligaments and torus uterinus, or visceral endometriosis involving the bladder and rectal wall(8), being an additional method to clinical examination and transvaginal or transrectal sonography in the evaluation of patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis(9).

Conclusions

The vast majority of patients had changes observed at the clinical examination. There is a correlation between the dimensions of the rectosigmoid nodules observed on MRI versus intraoperatively, this association being highly statistically significant.

MRI had a clearly superior specificity regarding parametric invasion, rectovaginal septum, sigmoid invasion and of the rectum.

If the ultrasound is useful in suspected cases of endometriosis, MRI plays an essential role in guiding the diagnosis of endometriosis(4). These two provide different and complementary information. Performing these investigations should be discussed depending on the type of endometriosis suspected, the proposed treatment strategy and the information provided to the patient.

MRI, as a noninvasive diagnostic tool, offers essential advantages regarding the classification and therapy planning for patients with DIE(5).

None of the evaluated imaging modalities were able to detect overall pelvic endometriosis with enough accuracy that they would suggest to replace surgery. The laparoscopy remains the gold standard for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis along with histopathological exam(2,6).

MRI features have a potential diagnostic utility in identifying the need for colorectal surgery in patients with DIE(7). Despite some limitations, magnetic resonance imaging is able to directly demonstrate deep pelvic endometriosis.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

-

Koninckx PR, Ussia A, Adamyan L, Wattiez A, Donnez J. Deep endometriosis: definition, diagnosis, and treatment. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(3):564–71.

-

Chamié LP, Blasbalg R, Pereira RMA, Warmbrand G, Serafini PC. Findings of pelvic endometriosis at transvaginal US, MR imaging, and laparoscopy. Radiographics. 2011;31(4):E77-100.

-

Bis KG, Vrachliotis TG, Agrawal R, Shetty AN, Maximovich A, Hricak H. Pelvic endometriosis: MR imaging spectrum with laparoscopic correlation and diagnostic pitfalls. Radiographics. 1997;17(3):639–55.

-

Chamié LP. Ultrasound evaluation of deeply infiltrative endometriosis: technique and interpretation. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45(6):1648–58.

-

Bazot M, Daraï E. Diagnosis of deep endometriosis: clinical examination, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and other techniques. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):886–94.

-

Brosens I, Puttemans P, Campo R, Gordts S, Kinkel K. Diagnosis of endometriosis: pelvic endoscopy and imaging techniques. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18(2):285–303.

-

Burla L, Scheiner D, Hötker AM, Meier A, Fink D, Boss A, et al. Structured manual for MRI assessment of deep infiltrating endometriosis using the ENZIAN classification. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;303(3):751–7.

-

Kataoka ML, Togashi K, Yamaoka T, Koyama T, Ueda H, Kobayashi H, et al. Posterior cul-de-sac obliteration associated with endometriosis: MR imaging evaluation. Radiology. 2005;234(3):815–23.

-

Manfredi R, Valentini AL. Magnetic resonance imaging of pelvic endometriosis. Rays. 1998;23(4):702–8.