Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of endometrial tissue, consisting of glands and stroma, outside the uterine cavity. The diagnosis of endometriosis remains an issue due to the nonspecific nature of symptoms and the difficulty in distinguishing between the pelvic pain caused by endometriosis and the pelvic pain caused by other medical conditions such as pelvic infection or various nongynecological medical conditions. Endometriosis of the ileum represents less than 7% of all gastrointestinal endometriosis cases. The presurgical diagnosis of ileal endometriosis is extremely difficult because the medical results obtained following the clinical examination and the imagistic methods are nonspecific. Many of the ileal endometriosis cases remain undiagnosed, causing real surgical emergencies, such as intestinal obstruction.

Dificultăţile de diagnostic al leziunilor endometriozice gastrointestinale cu localizare ileală

Difficult diagnosis in gastrointestinal endometriotic lesions with ileal localization

First published: 23 decembrie 2020

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.68.4.2020.4020

Abstract

Rezumat

Endometrioza se caracterizează prin prezenţa ţesutului endometrial, format din glande şi stromă, în afara cavităţii uterine. Diagnosticarea endometriozei rămâne o problemă din cauza naturii nespecifice a simptomelor şi a dificultăţii de a distinge între durerea pelviană datorată endometriozei şi cea cauzată de o infecţie pelviană sau de diverse afecţiuni nonginecologice. Endometrioza ileală reprezintă mai puţin de 7% din totalul cazurilor de endometrioză gastrointestinală. Diagnosticul preoperatoriu al endometriozei ileale este extrem de dificil, întrucât rezultatele obţinute în urma examenului clinic şi a investigaţiilor imagistice radiologice sunt nespecifice. O parte dintre cazurile de endometrioză ileală rămân nediagnosticate, determinând adevărate urgenţe chirurgicale, precum obstrucţia intestinală.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a gynecological disease with a chronic evolution, being common among women of reproductive age, affecting up to 15% of patients. The incidence of this pathology increases in cases of patients with chronic pelvic pain and infertility. Despite its high prevalence, this disease remains enigmatic, being called the “disease of theories”. With an incompletely elucidated etiology, endometriosis is defined by the presence of functional endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity(1,4).

Over time, several theories have been developed that justified the ectopic location of endometrial tissue, including the theory of retrograde menstruation. According to this, during an abundant menstrual flow, viable fragments of endometrial tissue are transported along the fallopian tubes, causing the implantation of endometrial cells and the secondary development of endometriotic lesions in the serosa of the intraabdominal or pelvic organs(1,3).

Other theories that explain the appearance of endometriotic lesions are: endometrioid metaplasia of mesothelial cells in the peritoneum, hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination of viable endometrial cells(1).

The most common locations of endometriotic lesions are represented by: ovaries, fallopian tubes, pelvic peritoneum, Douglas posterior sac and, last but not least, uterosacral ligaments. On the other hand, the gastrointestinal tract, vagina, rectovaginal septum or round ligaments are rarely affected. Regarding the extraabdominal locations of endometriosis, such as the lung, urinary tract, skin or central nervous system (CNS), they are very rarely mentioned in the specialized literature(1,6).

Regarding the involvement of the ileum, this type of endometriotic lesion is very rare and represents less than 7% of all endometriotic lesions with gastrointestinal (GI) localization(1).

Deep infiltrative endometriosis (DIE) is defined by the presence of endometrial implants, fibrosis and muscle hyperplasia under the peritoneum (>5 mm) and involves, in descending order of frequency, the uterosacral ligaments, the rectosigmoid colon, vagina and bladder(2).

Etiopathogenesis of gastrointestinal

endometriosis

The gastrointestinal tract is the most common site of extrapelvic endometriosis. Gastrointestinal tract endometriosis affects both women of childbearing age and adolescents or menopausal women in a proportion up to 37%(3). The most affected segment of the GI tract is the sigmoid colon, followed by the rectum, ileum, appendix and cecum. Small bowel lesions mostly involve the terminal ileum and represent 5-16% of the cases of GI endometriosis. Other locations of endometriosis in the GI tract, described in the literature but to a lesser extent, include the gallbladder, Meckel’s diverticulum, stomach, pancreas and liver(3).

The increased incidence of endometriotic lesions in the GI tract segments that are close to the uterus justifies the theory of retrograde menstruation(3). The superficial endometriotic implants in the serosa of the colon are often asymptomatic. On the other hand, DIE lesions cause severe gastrointestinal symptoms. Depending on the degree of invasion of the endometriotic lesion in the intestinal wall, endometriosis is classified histopathologically into four stages: stage 0 – the endometriotic lesion is found in the peritoneum and subserosal connective tissue, without reaching the plexus; stage 1 – the endometritic foci are located in the subserosal adipose tissue or adjacent to the neurovascular branches (subserosal plexus), rarely involving the external muscular layer; stage 2 involves the damage to the muscle wall and of the Auerbach plexus; stage 3 – the submucosal nerve plexus or even the mucosa is invaded(3).

Clinical picture of gastrointestinal

endometriosis

Most cases of GI endometriosis are symptomatic(4). When present, the symptoms of intestinal endometriosis depend on the location of the disease and also the depth of the invasion. When the lesions are limited to serosa, the symptoms are similar to those encountered in pelvic endometriosis(3). These include dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia and infertility. Other symptoms may be present, usually those that complete the clinical picture of an intestinal obstruction, especially when the endometriotic lesion of the intestinal wall causes a narrowing of the intestinal lumen, which will cause distension or stretching during peristalsis. However, the severity of the symptoms does not always correspond to the extent of the disease(3).

Establishing a solid preoperative diagnosis can be difficult due to the nonspecific symptoms. Many of the symptoms can mimic a wide range of diseases, including irritable bowel syndrome, infectious diseases, ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, ileocolonic intussusception, appendicitis and even malignancy(3,5,6). Symptoms generally include abdominal cramps, dyskinesia, rectal tenesmus, flatulence, constipation, melena, diarrhea, vomiting, defecation pain etc. The traditional cyclical pattern of symptomatology has not been confirmed by recent studies, which postulate that chronic noncyclic pelvic pain is the persistent symptom(3,7). Cyclic symptoms that worsen during menstruation have also been reported in a small number of patients(3,8). Because the intestinal mucosa is rarely affected, rectal bleeding may be an unusual symptom. Bleeding can also occur due to severe intestinal obstruction and ischemia(3,9). Acute intestinal obstruction due to stenosis is a rare complication, reported only in cases of severe small bowel involvement, or in the presence of dense pelvic adhesions(10). Also, the perforation of the intestine caused by endometriosis is an extremely rare entity, along with appendix rupture and intussusception(3,12).

Diagnosis of gastrointestinal endometriosis

The clinical suspicion of ileal endometriosis is important for optimizing the diagnostic imaging. In symptomatic patients, the surgical treatment is effective in resolving symptoms, laparoscopy being considered of choice. During surgery, a thorough examination of the abdominal cavity is essential for the detection of ileal endometriotic lesions, especially in patients with rectosigmoid colon involvement, as they are frequently associated with other lesions, which are often not detected by imaging diagnostic methods(13).

Often, the diagnosis of ileal endometriosis is delayed, because its clinical picture, often suggestive of an intestinal obstruction, is erroneously attributed to an inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn’s disease. Thus, the histopathological diagnosis is the one that attests the presence of the endometriotic lesion(1).

The general examination is very rarely useful in differentiating intestinal endometriosis from other intestinal diseases or pelvic endometriosis. In fact, many women with intestinal endometriosis are treated for irritable bowel syndrome before the final diagnosis is made(3,14).

At the clinical examination of the vagina or rectum, the presence of a knot of hard consistency can be detected, either at the level of the posterior vaginal fornix or on the rectal wall, which indicates an involvement of the intestine(3).

The accuracy of the diagnosis depends on the imaging technique used, the location and size of the lesion, as well as the expertise of the observer(3).

Radiological studies are often performed due to the nonspecific nature of patients’ symptoms and signs. However, there are no radiological or clinical results specific to endometriosis(3,15).

According to the latest studies, compared to surgery, it seems that, so far, there is no sufficiently accurate imaging method for the diagnosis of endometriosis(3). However, ultrasonography has demonstrated its value in this direction. The literature recognizes the importance of transvaginal and endorectal ultrasound in the diagnosis of rectosigmoid submucosal lesions(3).

Through transvaginal ultrasound (TVU), deep endometriotic lesions can be diagnosed, usually located in the anterior wall of the colon. The suggestive ultrasound image describes an irregular hypoechoic formation that often involves the left uterosacral ligament(3).

Transvaginal ultrasonography is considered a routine noninvasive diagnostic investigation, which can detect intestinal endometriosis with a sensitivity and specificity of 91% and 98%, respectively(3,16). Intestinal endometriotic nodules are in the form of heterogeneous, hypoechoic, rarely spiculated masses(16).

TVU with or without bowel preparation is effective in the noninvasive and preoperative detection of deeply infiltrative endometriosis of the rectosigmoid, and less of the ileum(17).

Ileal endometriosis usually involves the terminal ileum, 10 cm away from the ileocecal valve. In the diagnosis of this pathology, barium enema was also used. Following this investigation, the following aspects were found: extrinsic mass effect, annular lesions with spiky folds and steep edges, filling lesions etc. Therefore, the diagnosis of ileal endometriosis should also be considered when we detect something like this, after a barium enema in young, nulliparous women with abdominal or pelvic pain(18). Enteroclysis is a diagnostic imaging method used for small bowel analysis(3).

Although traditional computed tomography (CT) has been shown to be valuable in assessing pelvic endometriosis, it is limited in diagnosing the intestinal form of this pathology. Multidetector CT (MCTe) enterography appears to be useful in highlighting intestinal endometriosis(3). Moreover, MCTe can accurately identify the location of endometriotic nodules, as well as the degree of invasion of the endometriotic lesion in the intestinal wall(19).

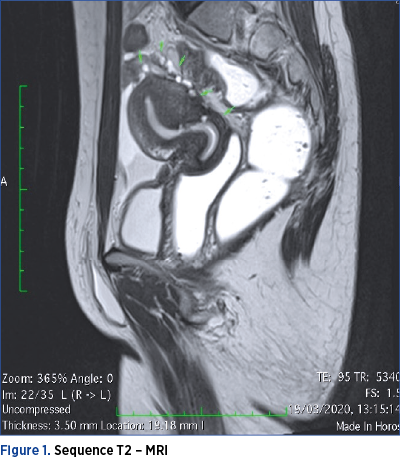

However, MRI is considered the most useful means of imaging diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis. MRI is useful for the diagnosis of multifocal endometriotic nodules and for defining anatomical relationships, with a sensitivity and specificity of approximately 90%. The endometriotic lesion can be visualized as a mass with high contrast, hyperintense focus on T1-MRI weighted images. Fat suppression on T1-weighted sequences is also suggestive of endometriosis, as it designates either hemorrhagic foci or secondary hyperintense cavities. On T2-weighted images, endometriotic nodules can be seen as hypointense masses with a signal close to that of the pelvic muscles(16). On both T1 and T2 MRI sequences, the ileum appears thickened, with the appearance of hyperintense round images(13).

Pelvic MRI or sonography may not show lesions beyond the visual field. Thus, the main challenge for the treating medical team is to determine the best diagnostic imaging method for deeply infiltrative intestinal endometriotic lesions. In the assessment of endometriosis located in the colon, there are several diagnostic techniques that use the retrograde distension of the colon. These include: Hydro Colo-CT, barium enema with double contrast and MRI colonography, all demonstrating a good accuracy(20). However, retrograde filling through the ileocecal valve is not constant. Therefore, none of these techniques is satisfactory for the analysis of the ileal intestinal segment. A combination of CT and enteroclysis has been attempted that may force the opening of the ileocecal valve to improve the diagnosis of terminal ileal endometriosis. However, this technique is invasive and requires ionizing radiation. This is an important disadvantage, especially for young patients interested in preserving fertility(20).

MRI enterography, which uses anterograde opacification, is a radiation-free examination technique that is widely used to investigate various pathologies associated with the small intestine(20).

3.0-T MRI enterography is useful in the preoperative diagnosis, as well as in mapping deep endometriotic intestinal lesions located above the rectosigmoid junction. The ability of MRI to map lesions can guide the surgeon during laparoscopic surgery, as some lesions may be camouflaged by adhesions and others may be erroneously considered superficial in the serosa(20).

3.0-T MRI enterography allows the obtaining of images with high spatial resolution and high contrast resolution, accurately illustrating the presence of deeply infiltrative endometriotic intestinal lesions. 3.0-T MRI enterography is a method that does not use radiation, allowing the mapping of endometriotic lesions and being well tolerated by patients(20).

Recent studies in the field support the utility of virtual colonoscopy based on computed tomography (CTC) for the diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis and have compared its usefulness with other diagnostic techniques. The CTC provides accurate information about endometriotic lesions located in both the large intestine and small intestine, providing a multiplanar and anatomical correlation between the lesion and a reference point (anal distance or ileocecal valve). Moreover, the accuracy in obtaining the image is higher compared to MRI, distinguishing very clearly the movements of the intestinal walls or feces(26).

However, the association of the two imaging investigations, MRI with CTC, improves the preoperative evaluation of the colorectal endometriosis, as well as the surgical therapeutic conduct(26).

In the study we performed from 2018 until present on 130 patients, aged between 20 and 41 years old, with planned surgeries for deep endometriosis, interventions performed by the same operating team, we assessed the sensitivity of imaging methods in the diagnosis of ileal endometriosis and multiple sigmoid endometriotic nodules.

Among the imaging methods used during the study, we mention transvaginal ultrasonography, MRI and CTC.

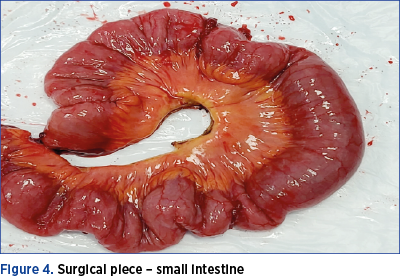

Of the 130 patients included in the study, seven patients were diagnosed with ileal endometriosis. In six cases, the diagnosis was made following scheduled surgery for another location of endometriosis. Of the seven patients, only one refused intestinal segmental resection, and in the remaining cases, ileal segmental resection was performed with ileo-colic anastomosis on the tapeworm of the cecum. These surgical procedures were performed minimally invasive: laparoscopic (five cases), robotic (one case).

It is worth mentioning that the seven patients performed both MRI and CTC. In only one case, the MRI raised the suspicion of ileal lesion, by visualizing an adhesive block formed by intestinal loops and omentum, as seen in Figures 1 and 2.

Also, the CTC detected only the endometriotic lesion with rectosigmoid colon localization.

Discussion

The preoperative diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis offers an advantage to the surgeon, but also a safety for the patient. Thus, surgical emergencies, such as intestinal obstruction, can be prevented(21).

The nonspecific results obtained after the clinical examination and preoperative imaging investigations postpone the diagnosis of this pathology and make the differential diagnosis more difficult. Although rare, ileal endometriosis should be considered when making the differential diagnosis of intestinal obstruction in women of reproductive age(22).

MRI is considered the most useful imaging diagnostic tool for intestinal endometriosis. The data present in the literature argue for a higher sensitivity and specificity of MRI, in terms of diagnosis of endometriotic lesions with rectosigmoid localization, compared to those located in the ileum(3,26).

Although most ileal endometriotic lesions involve the terminal ileum at a distance of 10 cm from the ileocecal valve, endometriosis is a multifocal disease, therefore several lesions with ileal or jejunal localization may occur. Because MRI enterography allows the complete exploration of the small intestine, this method may be more accurate than CT enterography in the diagnosis of ileal intestinal endometriosis(20).

No specific aspects are detected in multidetector helical CT enterography for an intestinal endometriotic lesion, but this imaging method, through its discoveries, can help diagnose ileal endometriosis, in a suitable clinical context(24,25).

However, MRI enterography and CT enterography are not routine investigations among women with gastrointestinal endometriosis, because multiple locations of deep endometriosis often coexist, and the clinical picture is nonspecific. Therefore, the suspicion of ileal endometriosis is low. Rarely, the clinical manifestations suggest an obstructive small bowel syndrome. In reality, there are subocclusive crises that are treated in emergency departments surgery as being caused by another pathology. It should be noted that, in the cases included in our study, the simultaneous presence of endometriotic lesions with ileal and rectosigmoid location was confirmed, as shown in Figure 3.

Therefore, following the intraoperative findings, the surgical team decided to perform the rectosigmoid resection simultaneously with the ileal segmental resection. The surgical piece is shown in Figure 4. Because endometriotic nodules which are located in sigmoid colon generate a higher degree of stenosis compared to rectal nodules, it has been found that CTC has a higher diagnostic accuracy than MRI. However, the combination of the two investigations, MRI and CTC, leads to an increased sensitivity in the detection of rectal and sigmoid colonic nodules(26).

Our study shows, so far, that none of the diagnostic imaging methods we used is effective in diagnosing ileal endometriotic lesions.

Conclusions

Given the nonspecific clinical picture of ileal endometriosis, as well as the low sensitivity of the imaging methods used, we can conclude, at least partial, that the diagnosis of this gynecological pathology is a real challenge for the medical team. An imaging method considered the gold standard in the diagnosis of endometriosis with ileal location has not yet been identified.

Therefore, further studies in this area of expertise are needed. In the specialized literature, we can find studies that support an increased concordance between intraoperative and preoperative findings on the presence of rectosigmoid endometriotic nodules, when in the preoperative diagnosis are associated two imaging methods, such as CTC and MRI, compared to each imaging diagnostic technique used individually(26).

The detection rate of ileal endometriosis is low, regardless of the imaging method used. However, in most cases, ileal endometriosis coexists with rectosigmoid endometriosis. Knowing this detail becomes an extremely useful tool for the operating team, that will carefully explore the ileum in order to discover possible endometriotic lesions.

Bibliografie

-

1. Karaman K, Ozok Pala E, Bayol U, Akman O, Olmez M, Unluoglu S, Ozturk S. Endometriosis of the Terminal Ileum: A Diagnostic Dilemma. Case Reports in Pathology. 2012;2012:74203.

-

2. Said TH, Azzam AZ. Prediction of endometriosis by transvaginal ultrasound in reproductive-age women with normal ovarian size. Middle East Fertility Society Journal. 2014;19(3):197-207.

-

3. Charatsi D, Koukoura O, Ntavela IG, Chintziou F, Gkorila G, Tsagkoulis M, Mikos T, Pistofidis G, Hajiioannou J, Daponte A. Gastrointestinal and Urinary Tract Endometriosis: A Review on the Commonest Locations of Extrapelvic Endometriosis. Adv Med. 2018;2018:3461209.

-

4. Prystowsky JB, Stryker SJ, Ujiki GT, et al. Gastrointestinal endometriosis. Incidence and indications for resection. Archives of Surgery. 1988;123(7):855–858.

-

5. Yantiss RK, Clement PB, Young RH. Endometriosis of the intestinal tract: a study of 44 cases of a disease that may cause diverse challenges in clinical and pathologic evaluation. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2001;25(4):445–454.

-

6. Dimoulios P, Koutroubakis IE, Tzardi M, et al. A case of sigmoid endometriosis difficult to differentiate from colon cancer. BMC Gastroenterology. 2003;3(1):18.

-

7. Shah M, Tager D, Feller E, et al. Intestinal endometriosis masquerading as common digestive disorders. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1995;155(9):977–980.

-

8. Jubanyik KJ, Comite F. Extrapelvic endometriosis. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 1997;24(2):411–440.

-

9. Levitt MD, Hodby KJ, van Merwyk AJ, Glancy RJ. Cyclical rectal bleeding in colorectal endometriosis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery. 1989;59(12):941–943.

-

10. Slesser AA, Sultan S, Kubba F, Sellu DP. Acute small bowel obstruction secondary to intestinal endometriosis, an elusive condition: a case report. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 2010;5(1):27.

-

11. Pisanu A, Deplano D, Angioni S, et al. Rectal perforation from endometriosis in pregnancy: case report and literature review. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010; 16(5):648–651.

-

12. Panzer S, Pitt HA, Wallach EE, et al. Intussusception of the appendix due to endometriosis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1995;90:1892-1893.

-

13. Carascco AL, Gutierrez AH, Hidalgo Gutierrez PA, Gonzales RR, Marijuan Martin JL, Zapardiel I, de Santiago Garcia J. Ileocecal endometriosis: diagnosis and management. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017;56(2):243-246.

-

14. Lea R, Whorwell PJ. Irritable bowel syndrome or endometriosis, or both? European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2003;15(10):1131–1133.

-

15. Cameron IC, Rogers S, Collins MC, Reed MWR. Intestinal endometriosis: presentation, investigation, and surgical management. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 1995;10(2):83–86.

-

16. Laganà AS, Vitale SG, Trovato MA, Palmara VI, Rapisarda AMC, Granese R, Sturlese E, de Dominici R, Alecci S, Padula F, Chiofalo B, Grasso R, Cignini P, D’Amico P, Triolo O. Full-Thickness Excision versus Shaving by Laparoscopy for Intestinal Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis: Rationale and Potential Treatment Options. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:3617179.

-

17. Hudelist G, English J, Thomas AE, Tinelli A, Singer CF, Keckstein J. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for non-invasive diagnosis of bowel endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(3):257-63.

-

18. Scarmato VJ, Levine MS, Herlinger H, Wickstrom M, Furth EE, Tureck RW. Ileal Endometriosis: Radiographic Findings in Five Cases. Radiology. 2000;214(2):509-512.

-

19. Biscaldi E, Ferrero S, Fulcheri E, Ragni N, Remorgida V, Rollandi GA. Multislice CT enteroclysis in the diagnosis of bowel endometriosis. European Radiology. 2006;17(2007):211-219.

-

20. Rousset P, Peyron N, Charlot M, Chateau F, Golfier F, Raudrant D, Cotte E, Isaac S, Réty F, Valette PJ. Bowel Endometriosis: Preoperative Diagnostic Accuracy of 3.0-T MR Enterography – Initial Results. Radiology. 2014;273(1):117-124.

-

21. Guerrero Lojano DA, Jimenez AG, Barrachina LM, Sanchez-Garcia JL, Gil-Moreno A, Suarez Salvador E. Multifocal ileal endometriosis. The Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. Nov-Dec 2020;27(7):1446-1447.

-

22. Arata R, Takakura Y, Ikeda S, Itamato T. A case of ileus caused by ileal endometriosis with lymph node involvement. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;54:90-94.

-

23. Li Destri G, Iraci M, Latino R, Carastro D, Li Destri M, Di Cataldo A. Intestinal obstruction from undiagnosed rectal and ileal endometriosis. Two clinical cases and review of the most recent literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2010;81(5):383-8.

-

24. Zouari-Zaoui L, Soyer P, Merlin A, Boudiaf M, Nemeth J, Rymer R. Multidetector row helical computed tomography enteroclysis findings in ileal endometriosis. Clin Imaging. 2008; 32(5):396-9.

-

25. Boudiaf M, Jaff A, Soyer P, Bouhnik Y, Hamzi L, Rymer R. Small-Bowel Disease: Prospective Evaluation of Multi-Detector Row Helical CT Enteroclysis in 107 Consecutive Patients. Radiology. 2004;233(2):338-344.

-

26. Mehedinţu C, Brînduşe LA, Brătilă E, Monroc M, Lemercier E, Suaud O, Collet-Savoye C, Roman H. Does computed tomography-based virtual colonoscopy improve the accuracy of preoperative assessment based on Magnetic Resonance Imaging in women managed for colorectal endometriosis? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(6):1009-1017.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Importanţa crucială a diagnosticului diferenţial al greţei şi vărsăturilor în sarcină. Propunere a unui ghid de diagnostic şi management

Greaţa, însoţită sau nu de vărsături uşoare, este considerată o componentă normală a fiziopatologiei sarcinii. Începutul simptomelor este primul se...

Fibroamele uterine asociate sarcinii – este fezabilă miomectomia în sarcină? Review şi prezentare de caz

Mioamele uterine afectează 2-10% dintre femeile însărcinate. Sunt tumori dependente hormonal şi, în consecinţă, 30% dintre ele vor creşte ca răspun...

Managementul prenatal şi postnatal în tetralogia Fallot

Anomaliile morfologice ale aparatului cardiovascular reprezintă o cauză majoră de morbiditate şi mortalitate neonatală. O ecografie fetală de rutin...

Omfalocel, scrot bifid, hipospadias şi micropenis: rezultate clinice în cazuri cu cariotip normal

Acest studiu îşi propune să descrie caracteristicile, monitorizarea şi managementul unei malformaţii complexe: omfalocel, hipospadias, scrot bifid ...