Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a leukocytoclastic vasculitis characterized by angeitis of small vessels induced by an IgA-mediated immune mechanism, which has predominantly cutaneous, articular and gastrointestinal clinical manifestations, with or without renal impairment. The authors present the case of a teenager with particular skin manifestations (purpuro-necrotic and petechial lesions), but also with joint involvement. The differential diagnosis was complex and the evolution was favorable under local and systemic treatment. On the long term, kidney involvement affects the prognosis of the disease.

Aspect particular al purpurei Henoch-Schönlein la copil – prezentare de caz

Particular aspect of Henoch-Schönlein purpura – case presentation

First published: 23 mai 2020

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Pedi.58.2.2020.3579

Abstract

Rezumat

Purpura Henoch-Schönlein este o vasculită leucocitoclazică ce este caracterizată printr-o angeită a vaselor mici indusă prin mecanism imunologic mediat de IgA, cu manifestări clinice predominant cutanate, articulare şi gastrointestinale, cu sau fără afectare renală. Autorii prezintă cazul unei adolescente cu manifestări cutanate particulare (purpuro-necrotice şi peteşiale), dar şi cu afectare articulară. Diagnosticul diferenţial a fost complex, iar evoluţia a fost favorabilă sub tratament local şi sistemic. Pe termen lung, afectarea renală determină prognosticul bolii.

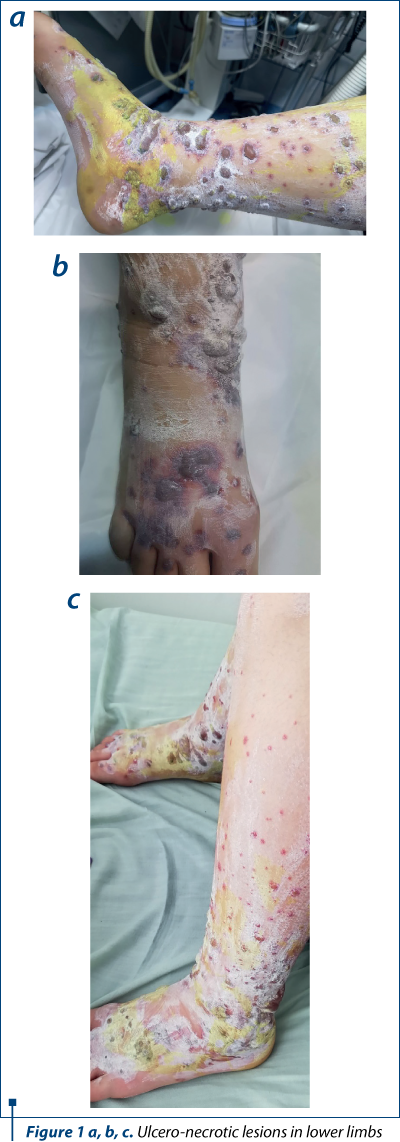

We present the case of a young girl, T.A., aged 13 years and 9 months, who was hospitalized in February 2020 in the 2nd Pediatrics Clinic of the “Sf. Maria” Emergency Clinical Hospital for Children Iaşi, Romania, for the investigation of some cutaneous lesions. These appeared at the lower limbs, bilaterally, had a vesicular maculopapular and purpuropetechial aspect, in various evolutionary stages, persistent at vitropressure, covered with hematous crusts and accompanied by pruritus. At the same time, the patient had pain, swelling and functional impotence at the level of the tibiotarsal joints and at the knee, bilaterally.

From the hereditary history, we note that the mother was 43 years old, and the father was 44 years old; the patient had three brothers and two sisters, all apparently healthy; they were not in evidence with chronic pathologies. There were no smokers in the family, the legal partner (mother) denies contact with BK-positive people or other infectious-contagious diseases in the family. As personal physiological antecedents, it is noted that she is the third child of the couple, born naturally, at term. She was vaccinated according to the national vaccination scheme in Great Britain, and the prophylaxis of rickets was performed until the age of 2 years old. The patient’s first menstruation was at 10 years old and the last one was two weeks before the current hospitalization, the menstrual cycle being regular.

The patient’s personal diseases history was insignificant, except for a respiratory tract intercurrence about a week before the presentation in the clinic, based on the mother’s statements. The child comes from the urban area, living in England for about 8 years, at the time of hospitalization being on vacation in our country. She was a seventh-grade student, not a smoker, and she had no contact with pets.

Thus, the patient’s history reveals a 13-year old female patient, without significant personal or heredo-collateral antecedents, domiciled abroad and with difficult anamnesis. She came to the emergency room for the appearance of a vesicular, maculopapular and purple petechial lesions in various evolutionary stages, persistent at vitro pressure, covered with hematous crusts and accompanied by pruritus, at the level of the lower limbs, bilaterally, in afebrility. She also associated pain, swelling and functional impotence in the tibiotarsal joints and at the knee, bilaterally. The symptoms had begun three days before hospitalization, with the appearance of purple petechial pruritous elements, initially in the foot, ascending in a short time to the suprarotulian level. After about 24 hours, the lesions acquired a vesicular appearance, with a hemorrhagic fluid inside, later associating the installation of edema, pain and functional impotence at the level of the aforementioned joints. A consultation was conducted in England, following which a topical treatment based on anti-inflammatory drugs and zinc oxide was administered. Despite the treatment, the rash persisted and soon the skin lesions spread and worsened.

The clinical exam upon admission revealed the following:

-

general state – moderately influenced, no fever;

-

nutritional status – normal (BMI=19.22 kg/m2; the 60th percentile);

-

skin – elastic, vesicular and purpuropetechial lesions, in various stages of evolution, at the level of the knees, legs and foot, bilaterally, covered with bloody crusts;

-

mucosa – normally coloured;

-

adipose tissue – normally represented;

-

lymph nodes – discrete bilateral laterocervical lymphadenopathy (maximum diameter 12 mm);

-

muscles – normal tonus, normotrophic, normokinetic;

-

osteoarticular system – arthralgias, swelling and functional impotence in the knee and tibiotarsal joints, bilaterally; active and passive mobilization difficult to achieve at the level of these joints;

-

respiratory system – normal chest, bilateral symmetrical costal excursions, physiological vesicular murmur on both lung areas, peripheral oxygen saturation 99%, respiratory rate 15 breaths/minute, productive cough and mucopurulent rhinorrhea;

-

cardiovascular system – normal precordial area, apexian shock in the left intercostal space V on the medioclavicular line, rhythmic heartbeats, no added murmurs, peripheral pulse 80 bpm, BP 110/75 mmHg;

-

digestive system – few dental caries, depressible abdomen, mobile with respiratory movements, painless upon superficial and deep palpation, normal stools;

-

liver, biliary tract, spleen – clinically normal;

-

uro-genital system – negative Giordano maneuver, physiological micturitions;

-

nervous, endocrine systems, sensory organs – conscient, collaborative, age-appropriate neuropsychosocial development, osteotendinous reflexes bilaterally and symmetrically present, absent meningeal signs.

The patient’s history and the clinical examination oriented upon a primary cutaneous lesion or another systemic disease with cutaneous involvement. The initial lesions had a petechiae-like aspect, appeared suddenly and then transformed into purple-petechial and vesicular eruptions, palpable and pruriginous. The articular involvement was also present. Thus, there was a suspicion of purpura, urticaria, vasculitis and juvenile arthritis, requiring further biological explorations.

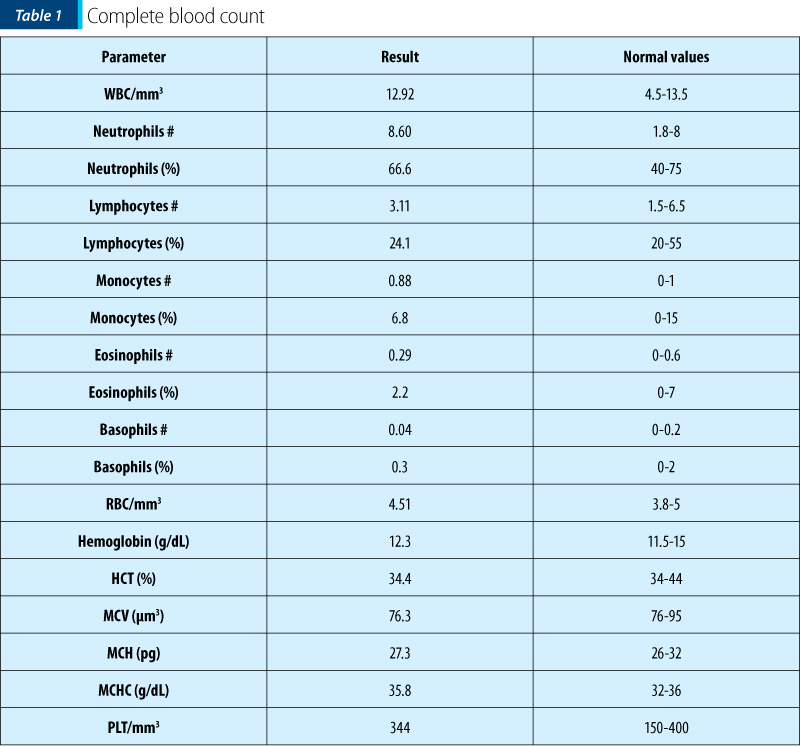

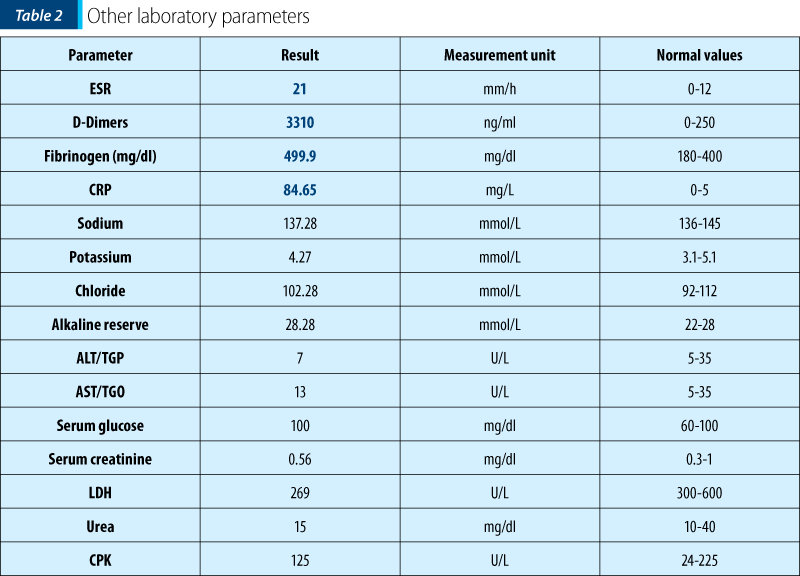

The biological investigations are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Complete blood count (CBC) and biochemical parameters were normal, the patient exhibiting just an important inflammatory syndrome.

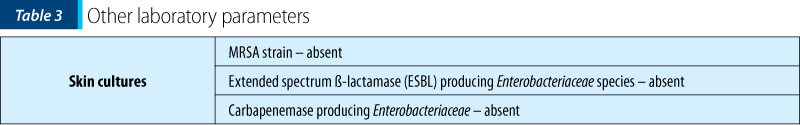

The normal number of platelets ruled out thrombocitopenic purpura. The bacterial infection required positive cultures, but both skin and lesion cultures, urine culture, throat swab and stool cultures were negative. Also, there was no blood detected in the stools.

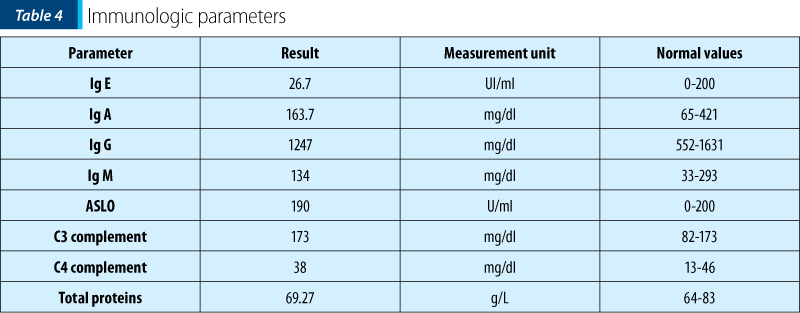

Further immunologic investigations (Ig A, G, M, E, complement) were within normal ranges, showing a nonspecific immune system involvement.

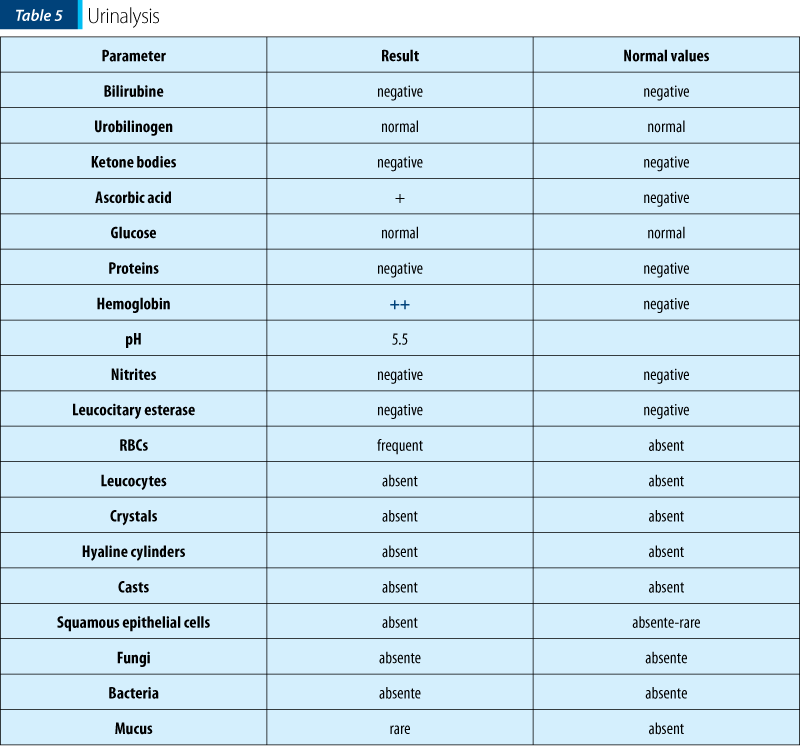

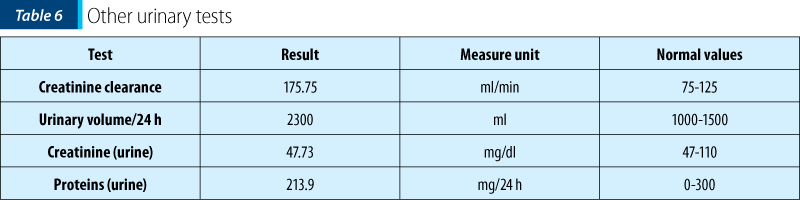

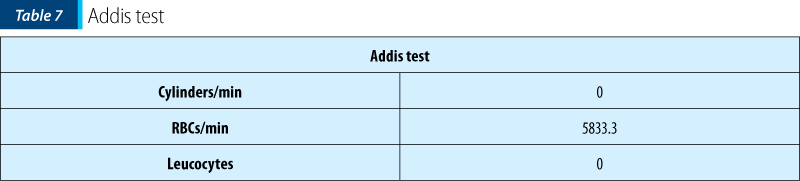

Urinalysis and Addis test showed the presence of RBCs in the urine, thus having a certain degree of renal involvement at the time of admission. When repeated, urinalysis and Addis tests were normal.

Anti-Mycoplasma (IgA, IgG and IgM) and anti-Parvovirus B19 antibodies were negative. The abdominal ultrasound revealed no abnormalities.

Thus, having the biological picture correlated with the clinical findings and the pacient’s history, the final diagnosis was Henoch-Schönlein purpura with skin and joint involvement, severe (ulcero-necrotic) form.

Vasculitis represents a heterogeneous group of diseases, characterized by inflammatory changes in the walls of blood vessels, associated with necrosis, vascular occlusion and tissue ischemia.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a leukocytoclastic vasculitis, characterized histologically by angeitis of small vessels induced by an IgA-mediated immune mechanism, which has predominantly cutaneous, articular, gastrointestinal and renal clinical manifestations.

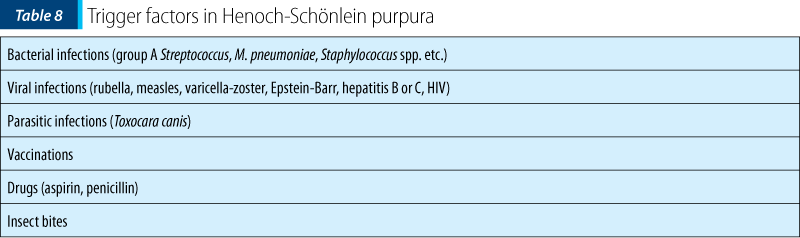

The etiology of the disease remains unspecified, with studies reporting a multitude of triggering factors involved in the onset of the disease. The most frequently involved remain the bacterial respiratory infections that often precede the onset of the disease.

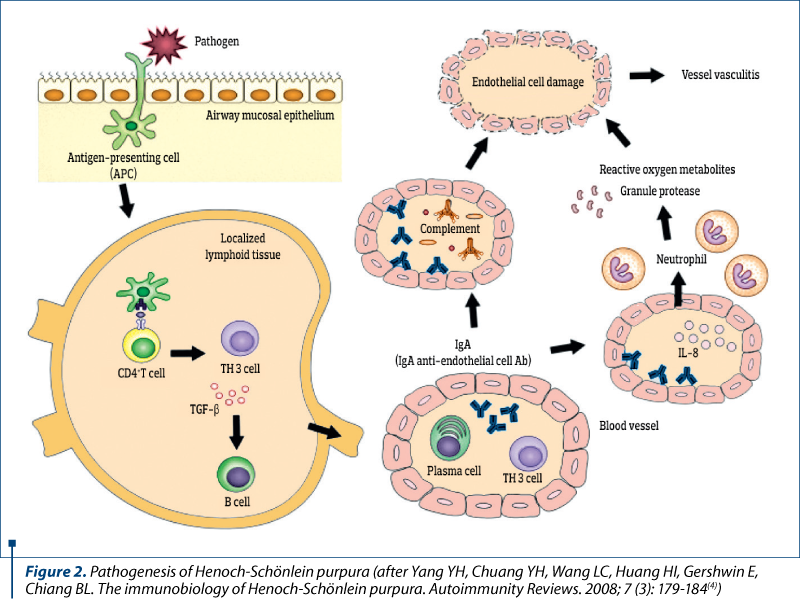

The main mechanisms that trigger the disease are the vascular storage of immune complexes, followed by local activation of complement on alternate pathway. 72% of patients with skin damage have immune complexes containing IgA, and those with nephropathy have IgA and IgG immune complexes. Endothelial and leukocyte activation, mediated by adhesion molecules, determine the release of mediators of inflammation: prostaglandins, interleukins (IL-1 and IL-6), TNF-a and TNF-b, endothelin-1, with necrotizing action on vascular endothelium.

There are several clinical forms of Henoch-Schönlein purpura:

-

the classical form;

-

Schönlein purpura defined by the isolated character of the articular manifestations;

-

Henoch purpura with double expression – cutaneous and digestive;

-

Seidlmeyer purpura (acute hemorrhagic edema in cockade of the infant and young child);

-

Sheldon necrotic purpura – individualized by petechial lesions with necrotic and scarring character that occur post- or intra-infectionally.

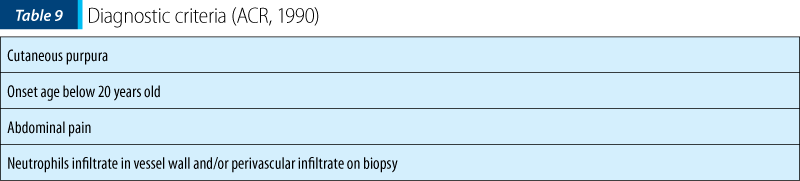

The positive diagnosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura is made upon the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria – Table 9. More than two criteria are necessary for the diagnosis, the first two being found in our case.

The differential diagnosis is made with several immunologic and infectious diseases (Table 10).

The following lines of treatment were applied:

1. Supportive and symptomatic treatment

-

Rest in bed in the acute phase, with subsequent avoidance of intense physical activity.

-

Adequate hydration.

-

Diet without salt.

-

Vascular trophic medication (rutoside and ascorbic acid).

-

Anti-inflammatory or analgesic medication to treat symptoms such as arthralgia, joint swelling, fever, general affected condition.

-

Calcium therapy.

-

Antihistamine treatment (loratadine).

2. Antibiotic treatment – clindamycin 900 mg/2 i.v., for 15 days.

3. Corticotherapy – dexamethasone 10 mg/2 i.v., with progressive decrease of doses, until discharge; the patient will continue corticoid therapy at home.

4. Close monitoring for the association of possible digestive and/or renal impairment.

5. Surgical treatment of skin lesions – cleaning, the evacuation of the contents of the blisters, washing with antiseptic solutions and dressing the wounds.

The evolution was satisfactory, the patient being discharged after only 18 days of hospitalization. She was continuously monitored for the appearance of complications, which fortunately did not occur. Usually, Henoch-Schönlein purpura is an autolimited disease, the patients presenting with relapses in the first year after the initial episode. In 95% of cases, there is a complete remission, but the rest of 5% of cases may exhibit complications, therefore close monitoring is required, both in acute phase and on the long term.

The possible complications of Henoch-Schönlein purpura are:

-

renal – CKD with end-stage renal disease; the renal involvement determines the prognosis on the long term;

-

digestive – intussusception, strictures, perforation, intestinal infarction, pseudomembranous colitis, appendicitis;

-

neurologic – infarction or subarachnoid, subdural, cortical hemorrhage, peripheral mono- and polyneuropathy;

-

skin necrosis.

The patient’s prognosis is good: she had no digestive or renal complications (urinalysis and Addis test normalized before discharge). Close monitoring and checkups at one month interval and then at three months are required to assess kidney function and the overall evolution.

This case is particular by its clinical presentation: blister-like lesions which could easily be mistaken for any other skin disease. The rapid evolution of the lesions was also impressive, in approximately 72 hours extending from the level of the foot to the lower part of the thigh, bilaterally, with the rapid transformation into vesicles and bubbles with hemorrhagic and sterile content. Ulceronecrotic lesions are the least common form of skin manifestation in Henoch-Schönlein purpura, but despite skin and joint involvement, the patient had no renal or digestive impairment.

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

- Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, García-Fuentes M, González-Gay MA. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood: two different expressions of the same syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997 May; 40(5):859-64.

- Szer IS. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1994 Jan; 6(1):25-31.

- Chen O, Zhu XB, Ren P, Wang YB, Sun RP, Wei DE. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children: clinical analysis of 120 cases. Afr Health Sci. 2013 Mar; 13(1):94-9.

- Yang YH, Chuang YH, Wang LC, Huang HI, Gershwin E, Chiang BL. The immunobiology of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2008; 7 (3): 179-184.

- Calvo-Rio V, Hernandez JL, Ortiz-Sanjuan F, et al. Relapses in patients with Henoch-Schonlein purpura: Analysis of 417 patients from a single center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Jul; 95 (28):e4217.

- Narchi H. Risk of long-term renal impairment and duration of follow-up recommended for Henoch-Schönlein purpura with normal or minimal urinary findings: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005 Sep; 90(9):916-20.

- McCarthy HJ, Tizard EJ. Clinical practice: Diagnosis and management of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Eur J Pediatr. 2010 Jun; 169(6):643-50.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Rolul imunoglobulinei E în patologia pediatrică

Implicaţiile IgE în patologie, deşi vag cunoscute şi acceptate, abia de curând au fost unificate şi descrise din prisma mecanismelor imunologice co...

Tulburări psihice asociate sindromului hiperactivitate/deficit de atenţie la copil

Sindromul hiperactivitate/deficit de atenție (ADHD) este o afecțiune neuropsihiatrică frecvent întâlnită la vârsta pediatrică. La școlari, frecvenț...

Imunoterapia modernă

Imunoterapia specifică (ITS), sau vaccinarea alergenică, este o variantă terapeutică utilizată de medicii alergologi pentru a reduce reactivitatea ...

Un caz rar de boală de stocaj a fibrinogenului hepatic la un copil – prezentare de caz

Boala hepatică de stocare a fibrinogenului este o afecţiune genetică rară, cu transmitere autozomal dominantă, caracterizată de acumularea de fi...