Eosinophilic esophagitis, although relatively recently introduced as a concept in specialty literature and among digestive diseases, presents an increasingly high incidence in the pediatric population. It represents a complex pathology, a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disorder, with various phenotypes and symptomatology, depending on age. This pathology may cause severe complications, such as esophageal strictures, which are associated with an increased risk of impaction of food in the esophagus. The quality of life of these children is often low and, unfortunately, the consequences of this disease will persist even in the adult life.

Impactul esofagitei eozinofilice asupra calităţii vieţii la populaţia pediatrică

The impact of eosinophilic esophagitis on the quality of life in children

First published: 30 decembrie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Pedi.68.4.2022.7524

Abstract

Rezumat

Esofagita eozinofilică, deşi relativ recent introdusă drept concept în literatura de specialitate şi în rândul afecţiunilor digestive, a evoluat cu o incidenţă din ce în ce mai mare în rândul populaţiei pediatrice. Esofagita eozinofilică reprezintă o patologie complexă, fiind o afecţiune inflamatorie cronică mediată imunologic, cu o paletă largă de fenotipuri şi cu o simptomatologie diversă, în funcţie de vârstă. Această afecţiune poate cauza complicaţii severe, cum ar fi stricturi esofagiene, care sunt asociate cu un risc crescut de impactare a alimentelor la nivel esofagian. Calitatea vieţii acestor copii este destul de scăzută şi unele consecinţe ale acestei boli vor persista inclusiv în viaţa de adult.

I. Introduction

The pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disorder, characterized by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and eosinophil-predominant inflammation (≥15 eosinophils per high-power field) of the esophageal mucosa, which affects individuals with a genetic predisposition(1,2,5). It is well know that the pathogenesis of eosinophilic esophagitis is extremely complex, being the result of a symbiosis between the genetic background of the person in cause, the immune factors and, of course, the environmental factors(1,2).

Looking at the constellation of this pathology, we can affirm the fact that, from a histopathological point of view, we have an esophageal epithelia dysfunction and, from an immunological point of view, an abnormal T-helper cell type 2 (Th2)-mediated immune response to environmental allergens, which all lead to esophageal lesion and dysmotility, and in the end, to the remodeling and fibrosis of the esophagus(1).

Many studies showed that the risk of developing this disorder is higher among first-degree family members, and also in monozygotic twins, in a percentage of 58%, while in dizygotic twins, it is found in approximately 36%(1). Also, some genes and enzymes were related with the occurrence of the eosinophilic esophagitis, such as: thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), desmoglein-1 (DSG1), calpain-14 (CALPN14), serine peptidase inhibitor Kazal types 5 and 7 (SPINK5 and SPINK7)(1).

It is important to know that, in the last decades, the incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis increased and it is believed that it will not stop here and that the disorder will be more and more frequently diagnosed, with a huge impact on the quality of life of these children. For example, in 2016, a meta-analysis evaluated the epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis reported by various countries and calculated an overall pooled incidence of 3.7/100,000/year (95% confidence interval [CI]; 1.7-6.5) which was higher in adults (7/100,000/year; 95% CI; 1-18.3) than in children (5/100,000/year; 95% CI; 1.5-10.9)(1). Also, a recent study published in November 2021, about the incidence of the disease in children from Alberta, Canada, for the period 2015-2018, showed that the incidence for 0- to 14-year-old children was 11.1 and 9.1 per 100,000 person years in Edmonton and Northern Alberta, being highest in the 10- to 14-year-old age group(1,3).

Furthermore, we should not neglect the important impact of the environmental factors in the pathogenesis of these disease, by developing or exacerbating it. We can mention the weather changes, living in a cold or dry climate, the pollen season, aeroallergens or the food(1,2). However, it should be noted that early-life environmental exposures, such as neonatal intensive care unit, maternal fever or septicemia, or pre-/postnatal antibiotics may play an important role in developing EoE(2).

Atopy is present in about 75% of patients with EoE and, also, asthma and IgE-mediated food allergy may be present(2).

When the genetically susceptible children ingest food, the antigenic proteins go to the esophagus and they trigger a prevalent T-helper type 2 (Th2) inflammatory response, producing large amounts of Th2 cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5 and IL-13(2). It is worth mentioning that IL-5 is one of the main mediators of EoE, as it induces eosinophil production and eosinophil trafficking to the esophagus, while IL-13 induces esophageal epithelial cells to secrete eotaxin-3, the other main mediator of EoE, which recruits and drives eosinophils and mast cells from the peripheral blood into the tissue(2). As a result, activated eosinophils and mast cells produce fibrosis, causing remodeling changes of the epithelium and subepithelium, responsible for the characteristic symptoms and complications of EoE(2,4).

II. Clinical presentation

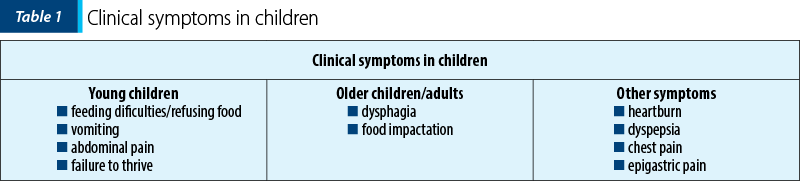

The eosinophilic esophagitis has a various number of phenotypes and symptomatology depending on age, which can vary from nonspecific to specific symptoms – for example, nonspecific symptoms affect children, while dysphagia and food impaction are predominant in adults. Of course, even though it affects patients of all age groups, it was seen more frequently in Caucasian males, and studies have shown a strong association with concomitant atopic conditions such as eczema/atopic dermatitis, asthma, rhinitis, and food allergies(2,3,6).

As pediatricians, while observing the infants and the young children, we can affirm that the most common symptoms are reflux-like symptoms, belching, vomiting, abdominal pain, food refusal, and failure to thrive(2). On the other hand, we have older children and adults who report dysphagia for solid food and even liquids, food impaction and, in the end, the impossibility of swallowing associated with chest pain(2).

This clinical pattern may be explained by recent studies which recognized the fact that EoE is a transmural disease, in which the eosinophilic infiltration permeates deep into the submucosa, the muscle layers and the neuronal plexus, and this could explain the disconnection between symptoms and the biological activity(5).

Studies have shown that approximately 30-50% of children who are transitioning to adulthood reported symptoms of dysphagia. It is well known that dysphagia suffers changes in time due to the fibrous remodeling and its effects on the formation of esophageal strictures, becoming, from an intermittent muscular phenomenon, a constant obstructive rigidity(5,6).

The impaction of a food bolus, usually observed in adults, often requires an emergency upper endoscopy for unblocking it and for improving the condition of the patient(6).

By being a complex pathology, we face a wide range of symptoms due to chronic inflammation which drives a progressive fibrosis and an esophageal remodeling, with repercussions on the quality of life of the patient(6).

In time, some patients may develop some coping mechanisms to alleviate the pain and to reduce the distensibility of the esophagus, such as: eating slowly, excessive mastication before swallowing, taking small bites, cutting foods into smaller pieces, lubricating food with different sauces, drinking fluid after most bites, and avoiding textured food such as meat and bread(5-7).

A group of otolaryngologists highlighted the increasing incidence of this pathology as well as the clinical picture they encountered, and they issued a warning about the necessity of knowing about EoE. They frequently encountered several otolaryngologic symptoms which were associated with EoE: rhinosinusitis, chronic cough, recurrent croup, hoarseness, and other aerodigestive symptoms refractory to gastroesophageal reflux therapy(7).

With all these symptoms, EoE is expected to have a significant impact on the quality of life and also on the psychosocial adjustment of the afflicted children and their families; they may develop social difficulties, anxiety, sleeping difficulties, depression and school problems(5-8). In conclusion, it should be taken in consideration by the family the practicing of psychotherapy sessions for an easier management of this pathology.

III. Diagnosis workup

Firstly, the diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis is based on several criteria: symptoms, endoscopic and histological changes.

Currently, unfortunately, noninvasive biomarkers are not accurate to diagnose or monitor EoE, but we hope in the near future to be able to diagnose with their help. Also, some minimal invasive diagnostic tools showed promise and need further evaluation.

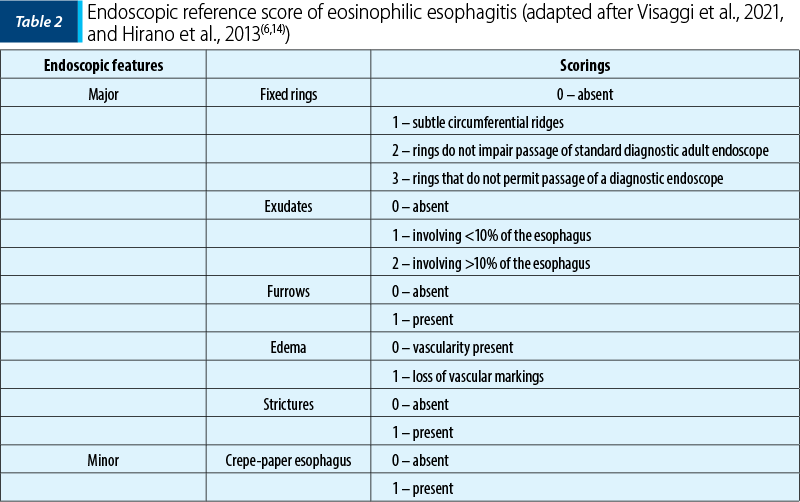

When we perform upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, which is the gold standard method, by taking at least six biopsies from different locations in the esophagus, we must look at the regions where the endoscopic mucosal abnormalities can be observed: mucosal edema, loss of vascular pattern, linear furrows, white specks and concentric rings(5,6,17). Endoscopic abnormalities may be present in up to 93% of patients with EoE, while in some cases the esophageal mucosa may appear normal, therefore it is recommended to obtain multiple biopsies from proximal and distal esophagus(5,6).

A normal esophagus at endoscopy does not exclude the diagnosis of EoE. Mucosal breaks (erosions or ulceration) are not findings of EoE and are indicative for other types of pathologies, so we must rule out other causes of abnormal eosinophilic esophageal infiltration, such as GERD, Crohn disease, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, connective tissue disorders, achalasia, infections, graft-versus-host reactions, and causative factors(5,6,17).

After obtaining the biopsies, they are sent to the pathologist specialist to be examined. Biopsies from patients with EoE show ≥15 intraepithelial eosinophils per high-power field; other findings include basal cell hyperplasia, vascular papillae elongation, eosinophil microabscesses and lamina propria fibrosis(5,6,9). It should be noted, however, that the size of a high-power field has not been standardized. This may alter the sensitivity/specificity of the lower threshold of diagnosis at 15 eos/hpf(5,9,17).

For example, absolute serum eosinophil count has shown a significantly correlation with the degree of esophageal eosinophilia, and to significantly decrease after steroid or proton pump inhibitor (PPI) induced histologic remission, but the accuracy was only 0.754(6,8).

Children commonly show an inflammatory-predominant esophageal pattern, with exudates, furrows and edema, whereas adults more frequently present rings and strictures, although different patterns may coexist in the same patient(6,10,11). The switch from an inflammatory to a fibrotic phenotype reflects the progressive remodeling of the esophagus caused by chronic inflammation(6,10,11).

In 2012, Hirano et al. validated a grading system for EoE, called Endoscopic Reference Score (EREFS), being predominantly used in the adult population, with good results in the prediction of EoE(6,14).

IV. Other methods

In our field of activity, it is important to know all the current diagnostic techniques in order to be able to make the correct diagnosis in the shortest time. Even though the upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsies represents the gold standard, we should also know other methods. For the beginning, we should know that we can perform barium esophagography, which is more sensitive than endoscopy for detecting esophageal stricture and diffuse small-caliber esophagus, while another technique used is unsedated transnasal endoscopy which has been used to assess esophageal mucosal inflammation through biopsy(8,9,14,17).

For the functional lumen imaging probe, a new endoluminal device, the EndoFLIP system, has initially demonstrated a significant reduction in esophageal distensibility in EoE patients, but further studies must be conducted to enhance the accuracy in order to predict the real biological activity of EoE(8). This functional test has shown a lack of correlation of eosinophil counts and esophageal distensibility, partially explaining the dissociation between inflammatory activity and symptoms in EoE(8). Furthermore, reduced esophageal distensibility predicted the risk for food impaction and correlated with endoscopically identified ring severity(8).

Nowadays, an instrumental examination currently being validated is the Esophageal String-Test (EST), which contains a nylon thread to the distal end which is attached to a gelatin capsule that captures eosinophil-associated proteins from the esophageal lumen. Until now, studies have shown that it has good correlation with eosinophilic infiltration in esophageal biopsy specimens in both children and adults(1,8,17).

Moreover, another capsule-based technology has been developed: the Cytosponge (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minn). Originally designed for assessment of the esophageal mucosa in patients with Barrett’s esophagus, it has been recently used to assess inflammation in adult patients with EoE(1,8).

V. Treatment and quality of life

The correct diagnosis can bring the right and optimal treatment for the patient, improving the quality of life. Untreated EoE is usually associated with persistent symptoms and inflammation, leading to esophageal remodeling resulting in stricture formation and functional abnormalities, and it also significantly impacts the health-related quality of life of the patients, impairing their social and psychological functioning(8). According to the recent consensus guidelines, proton pump inhibitors can be chosen as a first-line treatment option.

The goal of the treatment – even though it can be challenging for the patients with eosinophilic esophagitis – is, on the one hand, to alleviate the symptoms and to improve the quality of life and, on the other hand, to induce and maintain remission of eosinophilic inflammation below 15 eosinophils/HPF. Of course, another important aspect is to prevent the occurrence of the complications or to treat them.

Below we have a list with the treatments used in EoE:

-

proton pump inhibitors

-

topical steroids

-

elimination diet

-

biological therapy.

1. Proton pump inhibitors

In symptomatic children with histological findings of esophageal eosinophilia, a trial of PPIs is recommended for eight weeks and a second upper gastrointestinal endoscopy should be performed to see the evolution of the disease(8,17). Proton pump inhibitors have two main effects on EoE: the reduction of the acid reflux favors the restoration of the mucosal barrier and limits environmental allergens exposure, and it also reduces the levels of eotaxin-3, a Th-2 cytokine involved in eosinophil-mediated inflammation(8,17).

Several retrospective case series and studies conducted during four years evaluated patients with clinical, endoscopic and histological features compatible with EoE, showing a clinicopathological response to PPIs therapy(8,17).

They are used at high dosages (e.g., 40 mg of omeprazole are administered twice a day or 1-2 mg/kg in children).

The long-term side effects are:

-

dysbiosis

-

malabsorption

-

osteoporosis

-

possible higher risk for gastrointestinal and respiratory infections.

Several studies have shown that monotherapy with PPIs leads to clinical and histological remission in up to 50% of pediatric patients. However, when the treatment is discontinued, EoE recurs over a 3-6-month period(6,8,17).

2. Elimination diet

Current treatment strategies available to EoE patients are monotherapy with PPIs or combination therapy with dietary modification to exclude antigenic stimulation and topical corticosteroids(12).

The pediatric gastroenterologist should try to individualize for each patient the right dietary therapy, but the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines recommend an elementary diet for pediatric EoE patients who associate multiple food allergies, failure to thrive, unresponsive disease or are unable to follow a highly restricted diet(13,18,19).

Dietary therapy constitutes the only treatment targeting the cause of the disease: its purpose is to identify and exclude foods that trigger and maintain the disease from the diet. The exact pathophysiological mechanism by which food allergies cause EoE is not certain, but it is likely that both IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated processes are involved(15,18,19).

However, the use and interpretation of atopy patch tests are not standardized yet in EoE due to concordances between patch test results and EoE’s food triggers identified by biopsy(15).

It should be noted that the allergy testing cannot affirm the diagnosis, but could sometimes help identify foods and undoubtedly guide dietary therapy to resolve symptoms and avoid unnecessary exclusions(15).

The empiric approach six-food elimination diet consists of avoiding foods that are most associated with food allergy (cow’s milk protein, wheat, egg, soy, peanut, fish/seafood), and it was demonstrated histological remission in the majority of patients (74%) treated with this therapy(2,13,15).

However, a prospective observational outcome study in children with EoE treated with dietary exclusion of cow’s milk, wheat, egg and soy was performed. The objective was to assess the clinical, endoscopic and histologic efficacy of this treatment in EoE patients(13). The study recruited children (1-18 years old, diagnosed per consensus guidelines) from four medical centers(13). The study participants (n=78) were given a proton pump inhibitor twice daily and underwent a baseline esophagogastroduodenoscopy(13). The subjects were instructed on dietary exclusion of cow’s milk, wheat, egg and soy, and they were evaluated clinically, endoscopically and histologicalally after eight weeks(13). The results showed that, after eight weeks, 50 subjects were in histologic remission (64%), and the subjects’ mean baseline clinical symptoms score was 4.5, which decreased to 2.3 after eight weeks of four-food elimination diet (p<0.001)(13). After food reintroduction, the most common food triggers that induced histologic inflammation were cow’s milk (85%), egg (35%), wheat (33%) and soy (19%)(2,13).

Dietary elimination of whole protein with the use of amino acid-based elemental diets, even though highly successful for both symptom and histologic resolution, is very difficult to maintain on the long term, usually leading to nasogastric tube placement in 80% of the children(18). Some studies were conducted, for a duration of four to eight weeks. The use of amino acid formulas reduced eosinophil levels and demonstrated remission (defined as ≤10 eosinophils per high power field) in 75‐100% of children, with improvements, if not resolution, in clinical symptoms, resulting that the amino acid formula was more clinically effective than the use of the empirical elimination diet, where remission rates were 75‐81% and targeted elimination diet rates were 40‐69%(18).

Other ideas suggest the elimination of one or two foods (milk and gluten) that are more related to food allergy and increasing the restriction only in non-responders, but fewer studies were conducted to prove its efficiency(17,18).

3. Corticosteroids

The most common treatment in patients unresponsive to PPI is represented by topical corticosteroids, with an efficacy between 60% to 95% and with histological remission after two months of treatment(17,20).

Some randomized trials were conducted on children with EoE, showing that topical corticosteroids are effective for the induction of histological remission. It is well known that their mechanism of action is to reduce the esophageal fibrosis and to remodel and improve the integrity of the esophageal mucosal barrier.

Recent guidelines suggest fluticasone propionate (FP) dosages of 880-1760 mcg/day for induction and 440-880 mcg/day for maintenance, while the suggested budesonide dosages are 1-2 mg/day for induction and 1 mg/day for maintenance(6,17,20). It has been suggested that three months is an adequate timeframe to evaluate the histologic response to induction with FP(6,17,20).

Also, the systemic steroids are effective in inducing histological remission. Due to the so many well-known side effects that can occur after using systemic steroids, topical steroid therapy is recommended and systemic administration should be avoided and, when it is needed, it should be reserved only for severe dysphagia or for symptoms requiring fast withdrawal(20).

4. Biological therapy

Nowadays, many studies are conducted to discover monoclonal antibodies which specifically target inflammatory effectors involved in EoE pathogenesis. It is hoped that, by studying them, to decrease the adverse effects to a minimum and to offer more potent relief and long remission. However, the results are not so encouraging, the apparently favorable evolution being of short duration, with no significant clinical improvement. Many studies must be conducted to find the proper monoclonal antibody. Until now, the most studied monoclonal antibodies are mepolizumab, reslizumab and omalizumab.

IL-5 has an important role in the pathogenesis of EoE and it has been demonstrated to be overexpressed in the esophagus of patients with EoE, therefore two types of antibodies have been developed to target eosinophils: antibodies against IL-5 (mepolizumab and reslizumab) and an antibody against the IL-5 receptor (R)a (benralizumab)(2,17).

One study showed that, with mepolizumab, the children obtained a significant reduction in esophageal eosinophilia, which was still observed at week 24; in particular, up to 89.56% of patients reached a mean esophageal eosinophil count under 20/HPF(2). Mepolizumab showed the disappearance of eosinophilic microabscesses for at least 16 weeks after the last dose, with an increase in tissue eosinophilia; however, there was not a significant clinical improvement(2,17).

Recently, dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody which blocks interleukin 4 and interleukin 13, was approved for the treatment of atopic dermatitis, asthma and nasal polyps, and is in active clinical trials for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis, showing symptomatic and histologic remission of esophageal disease and lowering the need for EoE-directed therapy in patients with concomitant EoE(21). The conducted studies on patients revealed a significant improvement of symptoms, some patients reporting the complete resolution of symptoms after dupilumab initiation, while others needed reductions in the EoE treatment medications or the expansion of diet(21).

VI. Conclusions

We must acknowledge that the incidence and prevalence of EoE are increasing and that the optimal therapeutic approach to this disease has not been clarified yet. Many studies must be conducted with the biological therapy to see whether these monoclonal antibodies improve the quality of life of these patients, because they are an interesting therapeutic approach. For improving the quality of life, we must organize a multidisciplinary team, involving pediatricians, gastroenterologists, allergists, pathologists and dieticians, to be able to customize the optimal treatment for each patient.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

-

Barni S, Arasi S, Mastrorilli C, Pecoraro L, Giovannini M, Mori F, Liotti L, Saretta F, Castagnoli R, Caminiti L, Cianferoni A, Novembre E. Pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: a review for the clinician. Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 2021 November;47(1):230.

-

Cavalli E, Brusaferro A, Pieri ES, Cozzali R, Farinelli E, De’ Angelis GL, Esposito S. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children: doubts and future perspectives. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2019 August;17(1):262.

-

Burnett D, Persad R, Huynh HQ. Incidence of Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Characterization of the Stricturing Phenotype in Alberta, Canada. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2021 November; 2(4):136.

-

Hirano I, Aceves SS. Clinical implications and pathogenesis of esophageal remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2014 June; 43(2):297-316.

-

Kumar S, Choi SS, Gupta SK. Eosinophilic esophagitis: current status and future directions. Pediatric Research. 2020 January;88(3):345-347.

-

Visaggi P, Savarino E, Sciume G, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical, endoscopic, histologic and therapeutic differences and similarities between children and adults. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:1756284820980860.

-

Kumar S, Choi S, Gupta SK. Eosinophilic Esophagitis - A Primer for Otolaryngologists. JAMA Otolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery. 2019 April;145(4): 373-380.

-

Lucendo AJ, Molina-Infante J, Arias Á, et al. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5(3):335-358.

-

Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Katzka DA; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013 Apr;108(5):679-693.

-

Koutlas NT, Dellon ES. Progression from an inflammatory to a fibrostenotic phenotype in eosinophilic esophagitis. Case Reports in Gastroenterology. 2017 May-August; 11(2):382-388.

-

Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL, Rybnicek DA, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2014 April; 79(4):577-85.

-

Nhu QM, Aceves SS. Medical and dietary management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(2):156-161.

-

Kagalwalla AF, Wechsler JB, Amsden K, et al. Efficacy of a 4-Food Elimination Diet for Children with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(11):1698-1707.e7.

-

Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62:489-495.

-

Azzano P, Villard Truc F, Collardeau-Frachon S, Lachaux A. Children with eosinophilic esophagitis in real life: 10 years’ experience with a focus on allergic management. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2020;48(3):244-250.

-

Tourlamain G, Garcia-Puig R, Gutiérrez-Junquera C, et al. Differences in Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Europe: An Assessment of Current Practice.

-

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;71(1):83-90.

-

Papadopoulou A, Koletzko S, Heuschkel R, Dias JA, Allen KJ, Murch SH, Chong S, Gottrand F, Husby S, Lionetti P, Mearin ML, Ruemmele FM, Schäppi MG, Staiano A, et al., & ESPGHAN Eosinophilic Esophagitis Working Group. Management guidelines of eosinophilic esophagitis in childhood. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2014 January; 58(1):107-118.

-

Atwal K, Hubbard GP, Venter C, Stratton RJ. The use of amino acid-based nutritional feeds is effective in the dietary management of pediatric eosinophilic oesophagitis. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2019 December; 7(4):292-303.

-

Michelle H. Nutrition Guidelines for Treatment of Children with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Practical Gastro. 2014 June; XXXVIII(6).

-

Kanikowska A, Hryhorowicz S, Rychter AM, Kucharski MA, Zawada A, Iwanik K, Eder P, Słomski R, Dobrowolska A, Krela-Kaźmierczak I. Immunogenetic, Molecular and Microbiotic Determinants of Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Clinical Practice - A New Perspective of an Old Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 October; 22(19):10830.

-

Spergel BL, Ruffner MA, Godwin BC, et al. Improvement in eosinophilic esophagitis when using dupilumab for other indications or compassionate use. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128(5):589-593.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Tratamentul preventiv şi suportiv în arsurile majore la copil. Importanţa combaterii durerii şi utilizarea tratamentului nemedicamentos

Arsurile majore reprezintă o patologie importantă în chirurgia pediatrică, cu o rată mare a complicaţiilor (infecţii, dezechilibre electrolitice şi...

Complicaţii infecţioase la un copil cu leucemie acută limfoblastică (prezentare de caz)

Leucemia acută limfoblastică (ALL) este cea mai frecventă afecţiune malignă la copii, cu o prevalenţă de 25% şi o rată de vindecare de aproximativ ...

Implicaţii terapeutice chirurgicale şi ortopedice într-un caz de progerie

După o trecere în revistă a caracterelor clinice specifice ale acestui rar şi curios sindrom, autorii descriu cazul unei fetiţe cu progerie, la car...

Complicaţiile cirozei la un pacient cu atrezie de căi biliare

Ciroza hepatică este complicaţia redutabilă a bolilor hepatice cronice. Printre cauzele frecvente se numără atrezia de căi biliare, o patologie ...