Pitt-Hopkins syndrome is a genetic condition less debated in the literature in our country and even abroad. However, in daily practice, the clinical pediatrician may encounter this syndrome, which may mask or overlap other psychiatric conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder, or various aspects of certain neuromuscular disorders. The fact that not all children present the symptoms of this syndrome makes the differential diagnosis extremely difficult. Moreover, current approaches to this neuropathological syndrome have a limited impact.

Neuropsihiatria pediatrică dintr-o privire. O boală rară, ca o condamnare: sindromul Pitt-Hopkins

Pediatric neuropsychiatry at a glance. A rare condemnatory disease: Pitt-Hopkins syndrome

First published: 23 mai 2020

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Pedi.58.2.2020.3578

Abstract

Rezumat

Sindromul Pitt-Hopkins reprezintă o afectare genetică mai puţin dezbătută în literatura de specialitate de la noi şi chiar şi din străinătate. Cu toate acestea, pediatrul clinician se poate întâlni cu acest sindrom în practica sa de zi cu zi, care poate masca sau se poate suprapune cu alte afectări psihiatrice, cum ar fi tulburarea de spectru autist, sau cu anumite tulburări neuromusculare. Ca urmare a faptului că nu toţi copiii manifestă semnele şi simptomele caracteristice acestui sindrom, diagnosticul diferenţial este extrem de dificil. Mai mult decât atât, abordările curente ale acestui sindrom neuropatologic au un impact limitat.

Pitt-Hopkins syndrome (PTHS) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by developmental delay, epilepsy, distinctive facial features and possible intermittent hyperventilation followed by apnea(1). As more is learned about Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, the developmental spectrum of the disorder is widening, and can also include anxiety, autism(2), ADHD and sensory disorders. It is associated with an abnormality within chromosome 18; specifically, it is caused by an insufficient expression of the TCF4 gene(3). The neurobiological implications give the rarity of this neurodevelopmental disorder. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome arises from the haploinsufficiency of TCF4 (ITF2, SEF2, E2-2) as a result of autosomal dominant mutations at this gene locus on chromosome 18(4,5). The severe and systemic neurodevelopmental phenotypes of PTHS determined the specialized researchers and clinicians to develop and implement effective therapies to enhance the quality of life for these patients. The evidence that the expression of TCF4 is maintained in the brain, showing an untimely of expression during development(6), suggests that the treatment of PTHS cognitive deficits may be possible if TCF4 plays a significant role in the maintenance of neuronal function through adulthood.

At the time of presentation, those that attract attention are the facial features of the child:

-

deep set eyes

-

strabismus

-

myopia

-

marked nasal root

-

broad and/or beaked nasal bridge

-

prominent Cupid’s bow or tented upper lip (upper lip with the appearance of a tent)

-

everted lower lip

-

large mouth

-

widely spaced teeth

-

wide and shallow palate

-

ears with a thick and overfolded helix (the outermost fold of the ear).

Microcephaly and seizures may occur. Hypopigmented skin macules have occasionally been described. Children with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome typically have a happy, excitable disposition with nearly constant smiling and laughter. Affected children are described as very sociable; laughter may occur spontaneously or at inappropriate times. In any case, some children may be quiet or withdrawn into their own world (self-absorption). Episodes of aggression or shouting or agitation, often in response to unexpected changes in routine, occur as well. Additional behavioral issues are common and can include hyperactivity, anxiety, self-injury and shyness. Children with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome also exhibit stereotypic hand movements, which include hand clapping, hand flapping, flicking hands, hand washing, fingers crossing and frequent hand-to-mouth movements. Head shaking, head banging, body rocking, teeth grinding (bruxism) and hair pulling may also be seen. Children may repeatedly and repetitively play with a toy, and may show a fascination with one specific part of a toy(7).

Seizures can occur in under half of the individuals and usually begin in childhood, but sometimes are present from birth or develop late, as teenagers. Most children experience constipation, which can be severe. Gastroesophageal reflux has been reported in less than half of the affected individuals. Most patients have a high pain threshold.

Additional symptoms can include excessive drooling (especially when younger), severe nearsightedness (myopia), crossed eyes (strabismus), and abnormal curving of the lens of the eye (astigmatism). Abnormal curving of the spine (scoliosis) has occurred in a small number of individuals. Approximately one third of affected males experience failure of one or both testicles to descend into the scrotum (cryptorchidism)(8).

Diagnostic criteria

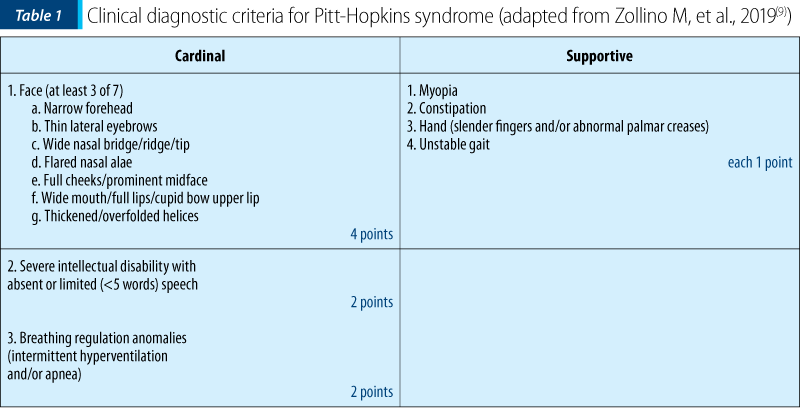

The clinical diagnostic criteria for PTHS are defined by cardinal (highly specific) features and supportive features. With a score of ≥9, the diagnosis of PTHS can be clinically confirmed (although molecular confirmation remains desirable)(9). This score can only be reached if at least two of the three cardinal features are present. A score of 6-8 needs further confirmation by molecular testing (Table 1). Also, Bayley Scales of Infant Development, readapted according to the autonomy of the clinic or research center, is used in order to asses mental and motor functioning(10). The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales – Survey Form (VABS) was used to assess personal and social self-sufficiency(11).

Differential diagnosis

In the differential diagnosis, the following diseases will be discussed, such as:

-

Angelman syndrome

-

Rett syndrome

-

Mowat-Wilson syndrome

-

Autism spectrum disorder.

Neuropsychiatry

Like many neurological diseases with a psychiatric impact, the neuropsychiatric features must be studied and taken into account carefully, separately, and not in bulk.

Neurological signs: distinctive facial characteristics, stereotype movements, impaired motor coordination, ataxia, hypotonia, atypical sensory profile.

Psychiatric symptoms: intellectual disability, very low cognitive abilities, behavioral impairments, social impairments, aggression, self-injurious behavior (e.g., pinching, hand biting, biting oneself), hyperexcitability.

In case of patients with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, a multidisciplinary approach is needed:

-

Pediatrician/pediatric neurologist/pediatric psychiatrist.

-

Medical genetics specialist/genetic map/genetic counseling.

-

Clinical laboratory testing.

Treatment

Because of the differences between ill people, currently there is no pharmacological treatment for this syndrome. Seizures and breathing problems represent the first important symptoms that need to be controlled and monitored. Early intervention services for infants and young children – which may include occupational, physical, speech and feeding therapies – are welcomed. An individualized education plan (IEP) for preschool and school-aged children is necessary. Behavioral therapies: children may benefit from treatments for autism spectrum disorder (such as applied behavioral analysis; ABA) or medications. Consider medication for important breathing problems. Some individuals with PTHS have reported the improvement of breathing problems with antiepileptic drugs or with acetazolamide.

Conclusions

Pitt-Hopkins syndrome is almost a forgotten disease, but with all of a sudden potential to be a diagnostic pitfall or a “hidden surprise”, masking other neuropediatric pathologies. This article tries to summarize and concentrate the primordial aspects of the disease. Because the diseases is like a condemnation, future research and studies to systematically investigate the cognitive, behavioral and neuropsychological profiles in an objective, quantitative and prospective manner, together with the natural history of PTHS, are needed in order to identify potential clinical biomarkers and outcome measures for testing future novel therapeutic interventions, all in the benefit of the little patients.

Conflicts of interests: The author declares no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

- Zweier C, Peippo MM, Hoyer J, et al. Haploinsufficiency of TCF4 causes syndrome mental retardation with intermittent hyperventilation (Pitt-Hopkins syndrome). American Journal of Human Genetics. May 2007; 80 (5): 994–1001.

- Weinberger RD. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome may point the way to autism treatments. May 2019. Available at: https://www.spectrumnews.org/opinion/pitt-hopkins-syndrome-may-point-way-autism-treatments/

- Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome; PTHS. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved: 2009-12-08.

- Amiel J, Rio M, de Pontual L, et al. Mutations in TCF4, encoding a class I basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, are responsible for Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, a severe epileptic encephalopathy associated with autonomic dysfunction. Am J Hum Genet. 2007; 80:988–993.

- Whalen S, Héron D, Gaillon T, et al. Novel comprehensive diagnostic strategy in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: clinical score and further delineation of the TCF4 mutational spectrum. Hum Mutat. 2012; 33:64–72.

- Rannals MD, Hamersky GR, Page SC, et al. Psychiatric Risk Gene Transcription Factor 4 Regulates Intrinsic Excitability of Prefrontal Neurons via Repression of SCN10a and KCNQ1. Neuron. 2016; 90:43–55.

- Marangi G, Ricciardi S, Orteschi D, et al. The Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: report of 16 new patients and clinical diagnostic criteria. Am J Med Genet A. 2011; 155A:1536-1545.

- https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/pitt-hopkins-syndrome/

- Zollino M, De Winter C, Huisman S, Menke L, Henniker RC. Diagnosis and management in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: First international consensus statement. Clin Genet. 2019; 95:462-478.

- Van der Meulen BF, Ruiter SAJ, Lutje Spelberg HC, Smrkovsky M. Bayley Scales of Infant Development – II. Dutch version. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger, 2002.

- Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cicchetti DV. Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales. Interview edition, Survey Form Manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service, 1984.

- Zweier C, et al. Further delineation of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: phenotypic and genotypic description of 16 novel patients. J Med Genet. 2008; 45(11):738-744.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Hepatită autoimună de tip 1 asimptomatică cu nivel normal al IgG şi deficit de IgA – prezentare de caz

Introducere. Hepatita autoimună (HAI) la copii este o boală hepatică cronică inflamatorie, cu un spectru clinic larg, de la o creştere izolată a t...

Cauză inedită de dispnee obstructivă la copil

Dispneea la sugar și la copilul mic reprezintă un simptom frecvent de adresabilitate într-un serviciu medical. Pentru medic, stabilirea diagnosticu...

Hemangiomul infantil − posibilităţi de abordare terapeutică

tumori vasculare, malformaţii vasculare, hemangiom, propranolol, scleroterapie

Intoleranţa la lactoză la copil

Intoleranţa la lactoză este o reacţie adversă alimentară cu mecanism neimun, datorată unei deficienţe în lactază, enzimă secretată de epiteliul i...