Schizophrenia is a psychiatric disorder characterized by the presence of positive symptoms (delusions and hallucinations), negative symptoms (flattened affect, alogia, avolition, abulia, anhedonia) and cognitive symptoms (affected working memory and attention, deficits in abstract thinking)(1). Delusion is a false belief based on incorrect inference about external reality that is firmly sustained despite what almost everyone else believes and despite what constitutes incontrovertible and obvious proof or evidence to the contrary. The belief is not one ordinarily accepted by other members of the person’s culture or subculture (e.g., it is not an article of religious faith). Religious delusions are a common symptom in schizophrenia patients, and the prevalence and the intensity of these symptoms vary depending on the society to which the patients belong to. For a religious belief to be classified as a delusion, the idea must be idiosyncratic, not representing the idea of a cult or subculture(2). The purpose of this paper is to show the difficulty of setting boundaries between religious delusions and religious belief. In the case of patients who are members of conservative religious cults, the differentiation between belief and delusion is hard to assess, this making the diagnosis, the therapeutic process and the recognition of relapse very difficult.

Delir religios la un pacient schizofren cu traseu EEG de tip iritativ în lobul temporal stâng

Religious delusions and schizophrenia in a patient with non-convulsive epileptic activity in the left temporal lobe

First published: 30 iunie 2022

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.69.2.2022.6635

Abstract

Rezumat

Schizofrenia este o tulburare psihiatrică ce este caracterizată prin simptome pozitive (delir şi halucinaţii), simptome negative (aplatizare afectivă, alogie, avoliţie, abulie, anhedonie) şi simptome cognitive (deteriorarea proceselor de gândire, afectarea memoriei de lucru şi a atenţiei)(1). Delirul este o credinţă falsă bazată pe interpretarea eronată a realităţii exterioare şi care este susţinută cu fermitate în ciuda tuturor argumentelor, a dovezilor de necombătut şi a evidenţelor care susţin contrariul. Credinţa respectivă nu este general acceptată de ceilalţi membri ai grupului cultural sau subgrupului căruia îi aparţine individul(2). Delirurile cu temă religioasă reprezintă un simptom comun la pacienţii cu schizofrenie, prevalenţa şi intensitatea acestuia variind în funcţie de grupul din care aceştia fac parte. Pentru a fi clasificat ca delir religios, credinţa trebuie să fie mai degrabă idiosincratică, decât acceptată într-o anumită cultură sau subcultură. Scopul acestei lucrări este de a arăta dificultatea stabilirii limitei între delirul religios şi experienţele religioase. În rândul pacienţilor care fac parte din culturi religioase conservative, este dificilă distingerea dintre credinţă şi delir, acest lucru îngreunând diagnosticul, procesul terapeutic şi recunoaşterea unei posibile recăderi.

Introduction

Schizoaffective disorder (SAD) is a chronic, potentially disabling psychotic disorder, common in clinical settings. SAD has been used often as a diagnosis for individuals having a mix of mood and psychotic symptoms whose diagnosis is uncertain. Its main feature is the presence of symptoms of a major mood episode concurrent with symptoms characteristic of schizophrenia, such as delusions, hallucinations or disorganized speech(3). The term “schizoaffective psychosis” was coined in 1933 by psychiatrist Jacob Kasanin. Dr. Kasanin recognized that some of his patients were experiencing symptoms suggesting both schizophrenia and mood/affective disorders. The first (1952) and second (1968) editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders regarded schizoaffective disorder as a subtype of schizophrenia. Even today, there is an ongoing debate about whether schizoaffective disorder should be classified as a subtype of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other mood disorder. The prevalence of schizoaffective disorder ranges from 0.32% to 1.1%. The patients have a better prognosis than the patients with schizophrenia, but a worse prognosis than the patients with mood disorders. The patients with the bipolar type of schizoaffective disorder experience both manic and depressive episodes, having periods of “highs” and “lows”. The depressive type of schizoaffective disorder is more common in older patients, whereas the bipolar type is more common in younger patients.

Case presentation

We present the case of a 32-year-old patient, with a background of four admissions in the Psychiatry Clinic Timişoara for psychotic symptoms. The patient followed medical treatment as prescribed ever since the first admission. The patient stopped taking medication two months before the current admission on his own accord. This time he was admitted as a psychiatric emergency presenting psychomotor agitation, dysphoria, irritability, auditory commentative and imperative hallucinations, paranoid, mystical and poisoning delusions, increased vital energy, excessive spending and reduced sleeping requirement.

Medical family history

Nothing of importance.

Personal history

Surgery for varicoceles in 2019.

Living and working conditions

The patient is unmarried, and his religion is neoprotestant Pentecostalism, living in a rural area. His living space is improper to the size of the family; he is living with his parents and brothers, 17 people, with proper basic utilities (electrical power, water), and the access to information is limited, as it is the tradition in his religion. His money income is secured by his job as a handyman in a factory; lately, his coworkers were included in his paranoid delusion, accusing them of conspiracy and persecution against him.

Substance use

The patient denies alcohol, drug or tobacco use as his religion is very strict.

Physical examination

All systems and organs were within normal limits. Vital signs: BP=131/88 mmHG, HR=87 bpm, RR=16/min, T=36.5 Celsius.

Psychic examination

Patient with appropriate body hygiene and clothing, oriented. The psychic examination is made with some difficulty, and visual contact is maintained intermittently during the interview.

Mimic-gestural expressiveness: according to the current psychopathological condition with minimal changes leaning to diminished.

Perception: commentative auditory hallucinations (“I hear voices from outside, of men and women talking about me, criticizing me, sometimes the voices of colleagues from work”) and imperatives, visual hallucinations (“I see angels and skulls, people near the fence”), olfactory and gustatory hallucinations (“the tastes of childhood have returned, I feel the taste and smell of strawberries and sour apples”).

Attention: hypoprosexia.

Memory: hypomnesia.

Thinking:

-

accelerated thinking and ideation, a weak logical association of ideas, phrases, sentences and structural elaboration;

-

delusional paranoid ideas of persecution, prejudice, and poisoning (“The colleagues want to poison me at work, also my brother gave me a glass of water and I felt the altered taste of water”);

-

mystical delusions (“I feel God and the Holy Spirit, my mission is to make people better, I am punished because I sin with my mind, I have had sexual dreams and it is not allowed. I stopped going to church because most people there are fake and sinful and don’t deserve to be there”);

-

sensitive-relational ideas;

-

xenopathic influence, ruminations on religious and disease topics, poor abstract thinking with a tendency to hyperconcrete thinking.

Executive disfunction: deficits in working memory, deficits in problem-solving, organization, planning, sequencing, prioritization and execution of complex activities.

Affect: dysphoric-irritable mood, suspicious, anxiety secondary to delusional ideas, low tolerance for frustration, intrapsychic tension.

Volition: increased level of will, secondary to disordered thinking content, behavior driven by the religious beliefs which make up a big part of the patient’s life.

Behavior: increased vital energy, clastic behavior at home, excessive spending, restricted activities and interests with a focus on religious topics.

Appetite: normal.

Circadian rhythm: reduced sleep required.

Insight: lacking “everything I feel and happens to me is because of the Holy Spirit”.

Disease history

The patient was first admitted to the Psychiatry Clinic of Timişoara in 2009 for a clinical presentation of psychosis, with the diagnosis of a paranoid psychotic episode, thereafter he was admitted four more times for relapses due to poor adherence to treatment, the diagnosis being switched to acute psychotic disorder. At the last admission, the patient presented a relapse with aggravated psychotic symptoms and an overlap of mood disorder following the interruption of psychiatric treatment on his own accord.

The following psychometric scales were used:

-

PANSS measured in dynamic score (P=29, N=34, G=53, Total=116; P=32, N=29, G=47, Total=98; P=14, N=21, G=28, Total=63).

-

Young Mania Scale measured in dynamic – 13 and 3, respectively.

-

The Birchwood Insight Assessment Scale with absent insight for disease, absent insight for symptoms, and present insight for the need for treatment.

-

SANS scale with a score of 14 for flattening, 17 for alogia, 4 for avolition, 7 for anhedonia, and 5 for attention.

-

SCL-90 – high score for psychoticism and sensitivity.

-

Word-association test.

-

Similarities and proverbs with poor abstract thinking with a tendency to hyperconcrete thinking.

Psychodiagnostic examination

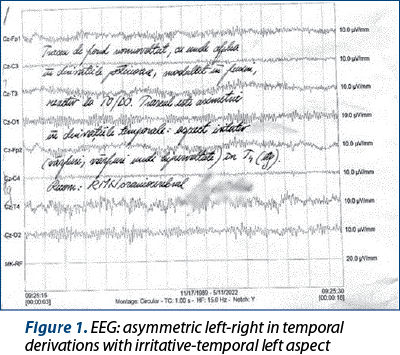

Person in need of sensitive censored recognition, emotional lability with explosiveness, tendency to persevere with adhesiveness/viscosity. Signs of mixed mood swings with depressive-dysphoric dominance and hysteriform restlessness. Isolated signs of psychosis without massive decompensation at the time of evaluation. Discrete signs of organic damage (Figure 1).

Neurological examination

Objective neurological examination without signs of focal irritations, discrete post-neuroleptic Parkinson’s syndrome.

Positive diagnosis

Based on the anamnesis, the clinical examination, the psychic examination, the psychodiagnostic examination, the psychometric scales and the history of the disease, the diagnosis of manic schizoaffective disorder, F25.0, is established; the current episode of the disease meets the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia (paranoid delusional ideas of persecution, poisoning, mysticism, xenopathic influence, altered interpersonal relationships), as well as a manic episode (dysphoric-irritable mood, increased distractibility, increased vital energy, excessive spending, reduced sleep).

Differential diagnosis

1. Schizophrenia-like organic delusional disorder (F06.2)

For a positive diagnosis, the clinical symptoms should be the consequences of brain dysfunction or a general organic disease that can cause a brain disorder (objectified by somatic examination and paraclinical examinations), including hormonal imbalances. Both MRI and other paraclinical examinations did not show an organic cause for the present symptomatology.

2. Mental and behavioral disorders due to the use of psychoactive substances. Psychotic disorder (F1X.5)

Due to the clinical and toxicological examination, the diagnosis cannot be sustained.

3. Schizophrenia

In this case, the clinical picture is dominated by both symptoms characteristic of schizophrenia and symptoms characteristic of a manic episode.

4. Schizotypal disorder (F21)

The patient already meets the criteria for the diagnosis of schizophrenia.

5. Delusional disorders (F22)

Delusions should be long-lasting and be the only or most prominent clinical feature. In this case, the patient already meets the criteria for the diagnosis of schizophrenia and affective disorder.

6. Brief psychotic disorder (F23)

The onset would have been acute (maximum two weeks) and the duration would not exceed 1-3 months; in this case, delusions, hallucinations and the affective symptoms are long-lasting.

7. Manic episode with psychotic symptoms (F30.2)

Manic episodes may have psychotic symptoms. If hallucinations and delusions are present in an affective disorder, they develop in the context of the affective disorder and do not persist after the affective episode is remitted.

8. Bipolar affective disorder, manic episode with psychotic symptoms

There must be at least one more emotional episode in the history of the disease (manic, hypomanic, depressed, mixed); this patient has only presented psychotic episodes.

Current treatment

During hospitalization, the patient received treatment with haloperidol oral 100 drops/day with gradual decrease until the subsequent withdrawal from the treatment regimen, paliperidone 12 mg/day, then continued with Xeplion® 150 mg long action administered monthly according to the guidelines, trihexyphenidylum 6 mg/day, valproic acid + salts 2 000 mg/day with a gradual decrease to 1 000 mg, clonazepam 3 mg with a gradual decrease to 2 mg/day, zopiclonum 7.5 mg/day.

Recommended treatment on discharge

He is monitored at the level of the outpatient clinic, being necessary for the patient to be periodically reassessed in terms of vital functions, weight and lipid profile.

At this stage, the simplification of the treatment takes place, being prescribed the lowest effective doses of medication.

The recommended medication for discharge is: Xeplion® 150 mg administered monthly, Orfiril long® 1000 mg/day, trihxyphenidylum 6 mg/day, clonazepam 2 mg/day with the gradual elimination of the medication, zopiclone 7.5 mg/day as needed.

Psychosocial interventions

1. Psychoeducation. It must be started early due to the patient’s tendency towards isolation and non-communication. Its role is to inform both the patient and his relatives about the symptoms, treatment and recognition of the signs of relapse, but it also helps the family members to understand the evolution of the disease, to develop appropriate responses to the patient’s needs, to know the side effects of medication, but also how to administer the medication.

2. Supportive therapy. It must encourage the patient to have confidence in his strengths, and deal with the impact of the disease on interpersonal and professional relationships.

3. Cognitive-behavioral therapy. It is an intervention that encourages the patient to make connections between his thoughts, feelings and actions, and try to change his psychotic experiences and symptoms or the effect they have on his thinking.

Behavioral elements:

-

monitoring symptoms, using a journal;

-

distraction techniques – concentration strategies for “ignoring” the voices;

-

anxiety management through relaxation techniques;

-

token economy;

-

computer cognitive remediation techniques (stimulates attention and memory).

4. Social skills training. It aims to improve the patient’s functioning by learning the necessary behaviors in society (through intervention in eye contact and relationship skills).

Complications

Medication: extrapyramidal syndrome, anticholinergic effects, sedation, hyperprolactinemia, transient alopecia, heart rhythm and conduction disorders, gastrointestinal side effects, xerostomia, constipation, headache, dizziness, insomnia.

Psychiatric: Suicide – the suicide rate of patients with schizoaffective disorder is 10%.

Depression.

Anxiety.

Substance abuse.

Death due to other medical conditions, by decreasing the treatment adherence.

Falling injuries due to sedation.

Social: Decreased quality of life.

Social dysfunction.

Peculiarities of the case

Genetic and epigenetic factors are involved in the etiopathogenesis of schizoaffective disorder. Although the patient has a large family of 17 members, he is the only person with a diagnosed psychiatric illness. Another peculiarity of the case is the EEG changes with irritative-temporal left aspect.

Evolution of the disease

In the evolution of schizoaffective disorder, there can be several types of episodes, and these can be purely affective or schizophrenic episodes, but there is the possibility of a combination between them, as follows:

-

all schizoaffective episodes;

-

part schizoaffective episodes and part of schizophrenic type;

-

part schizoaffective episodes and part affective;

-

some of the schizoaffective episodes may meet the criteria for brief transient psychotic disorder or delusional disorder.

From an evolutionary point of view, without treatment, the following eventualities can occur: single episode, recurrent episodes without deficit, recurrent episodes with a deficit, or continuous evolution.

The evolution can be favorable, with socioprofessional reintegration, if there is good compliance and adherence to treatment.

Positive prognostic factors: acute onset of disease, paranoid subtype, social support network present, good socioprofessional functionality, presence of affective symptoms, lack of genetic component.

Negative prognostic factors: onset at a young age, male, partial adherence to treatment, partial response to treatment, presence of cognitive symptoms, absence of insight.

Discussion

The patient was monitored monthly for 10 years in the outpatient clinic while following treatment with psychiatric drugs. Affirmatively, the psychotic symptoms, both the hallucinations and the delusions with mystical content, persisted, the patient finding them a religious explanation. The delusional mystical theme was influenced by the patient’s and his family’s adherence to the religious cult; thus, the religious principles play a major role in the patient’s hierarchy of values. However, the absurd nature of mystical ideas that are not accepted by other members of the family and the religious community to which they belong thus justifies the semiological framing in the delusional ideation. The family also considered it necessary to hospitalize the patient only following an affective decompensation, the psychotic symptoms were not a cause for concern. Increased perception and feelings of communion with the “divine” may be common in psychotic episodes and mystical experiences. The onset of an acute psychotic episode may be preceded by a state of confusion and acute anxiety which is then replaced by the sudden “understanding” by the individual of the “significance” of the experience, the revelation, also the onset of schizophrenia is usually slowly insidious distinguishing it from mystical experiences(4). Affective flattening, language, and thinking deficits usually do not accompany mystical experiences. In literature, it has been shown that belonging to a religious group and the intensity of faith measured by scales are an important factor in the occurrence of religious and grandeur delusions, the patients with moderate or non-religious faith being much less likely to have such delusions. At present, people with intense faith are considered to have these delusions because faith is an important part of their life, to the detriment of other aspects of life(5). Another study showed that schizophrenic patients of the Christian religion have predominantly delusions of persecution and guilt, and those of the Muslim and Judaic religions have a much lower frequency of these delusions, but more frequently have delusions of special mission and grandeur(6). Belonging to a religious group of low or moderate faith is a positive prognostic factor because it protects patients from certain harmful behaviors such as substance abuse, suicide, dangerous sexual behaviors, increased adherence to treatment, and gives the patient meaning and purpose. Despite the presence of this condition, religious groups are also a very important support network when they are not overly strict and rigid. Schizophrenic patients with religious delusions also have very low scores on cognitive biases scales and have inflexible and rigid thinking; these are measured by questions that test the possibility of finding an alternative answer to the realities of the patient’s world. It has been found that religious delusions are more likely to be accompanied by delusions of grandeur and high levels of positive symptoms, including hallucinations, influence or passivity and unusual behavior(5). According to literature, neurological patients with temporal lobe epilepsy presented hyper-religiousness as a psychological characteristic(7).

Conclusions

By presenting this case, we want to show the importance of understanding certain boundaries between religious delusions and religious beliefs, the psychoeducation of both the patient and family members being very important, recognizing the symptoms of possible relapses and the need for treatment improving the prognosis. It is also beneficial to understand and maintain aspects of religion that improve the quality of life and education about detrimental religious aspects that increase the rate of relapse.

Bibliografie

-

World Health Organization (WHO). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. Genève, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1993.

-

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5). Barking, England: Lulu.com; 2020.

-

Miller JN, Black DW. Schizoaffective disorder: A review. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry: official journal of the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. 2019;31(1):47–53.

-

Parnas J, Henriksen MG. Mysticism and schizophrenia: A phenomenological exploration of the structure of consciousness in the schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Conscious Cogn. 2016;43:75–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2016.05.010.

-

Iyassu R, Jolley S, Bebbington P, Dunn G, Emsley R, Freeman D, et al. Psychological characteristics of religious delusions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:1051–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0811-y.

-

Buckley P. Mystical experience and schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1981;7:516–21.

-

Devinsky O, Lai G. Spirituality and religion in epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behaviour: E&B. 2008;12(4):636–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.11.011.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Tratamentul farmacologic în schizofrenie

Ghidurile de tratament oferă recomandări bazate pe dovezi pentru a-i asista pe practicieni în situații clinice specifice. Ele reprezintă un instrum...

Episod psihotic acut indus de sertralină la un pacient cu tulburare obsesiv-compulsivă şi tulburare anxios-fobică

Inhibitorii selectivi ai recaptării serotoninei sunt cele mai utilizate antidepresive la nivel global. Sertralina este utilizată pe scară largă în ...

Intervenţie fenomenologică analitic‑existenţială orientată către recuperare, după un prim episod psihotic de spectru schizofren

Existential-analytical intervention for recovery, after a first psychotic schizophrenic episode

Relaţia dintre acceptarea necondiţionată a propriei persoane şi fuziunea cognitivă în psihoză

The term psychosis was used for the first time by Canstatt in 1841 and then published in a study in 1845 by Ernst von Feuchtersleben.