Death – or, more precisely, living one’s own death – is a feeling integrated into the depth of any human being. That such an intimate feeling is kept in silence for most of the time is no wonder, given that so many fundamental psychological phenomena (such as “the lived body”, or the corporal cenesthetic sense), in their their turn, remain hidden and silent, until an event or the pathology bring them to the forefront of existence.

When someone begins to think his own death, his consciousness is doubled in two spaces, one of reality and one of non-reality, but also of non-being. That second space, the person tries to transform into a conceptual, virtual space, in which the concept of non-being is integrated with that of a living being, in his consciousness, because the consciousness is not synonymous with the feeling of life. Taking into account some possible end is not in any way close to reverie, of imagining the state of non-being. For the living subject, death is something that is imposed from outside, it is an exogenous phenomenon, many rebelling against it, this rebellion being triggered by the feeling of injustice.

The majority of self-murderers pertain to the category of despair, indifferent of the cause or causes that have generated the despair. The despair is a psychiatric state that imposes itself to the subject who lives it, and its load is unbearable. The despair cannot be approached progressively; the man falls in despair unexpectedly as sitting on the brink of a precipice.

But what sense could get the act, the action, the summing of behaviors that ultimately transform the being in the non-being?

If death is absurd for the living ones, the self-murderer seeks to give it a sense, an ultimate sense. Most of the times, this is represented as an act of aggression, self-directed, maybe sometimes from the lack of possibility to direct it to somebody else. In that way, the autoaggression is in continuity with the “global” personality, the self‑destructive behavior, not always explained by immediate causes, but not outside the circumstances(1).

Let us say together with Sartre: “The death is absurd as it does not pertain to any project. What would be life if it would not have, in a potential future, an expectance?... In a word, the consciousness, that for itself in the measure as it projects into the future, asks again and again an and after. Just because this for itself is the being that pretends again and again an and after, there is no place for death in the being that is for itself” (translated from French)(2).

The judgement of the suicidal act of a creative person cannot be done only on the basis of criminological, sociological, psychological, psychopathological criteria; at these, we need to add the factor “creative energy”, “creative vitality” and even that of “creative consciousness”.

The personality of an artist, of a creator, constitutes a faithful seismograph of the pulse of his time(3). The value of the creation does not reside only in their capacity to give esthetical emotions but, by its repercussions, to play a model role in the society. Creation is a supreme fulfillment of the personality, the artist being gifted with peculiar cognitive, intuitive, emotional capacities, transfering himself in the emotions of the other ones.

In the development of the creative act, the trajectory of the artist’s life may take often a tragic course. As Tudor Vianu said: “The interest of the artistic life does not coincide with that of personal conservation. The artist does not live his life, but consumes it. The pain felt by an artist may become his creative impulse, unchained by that signal”.

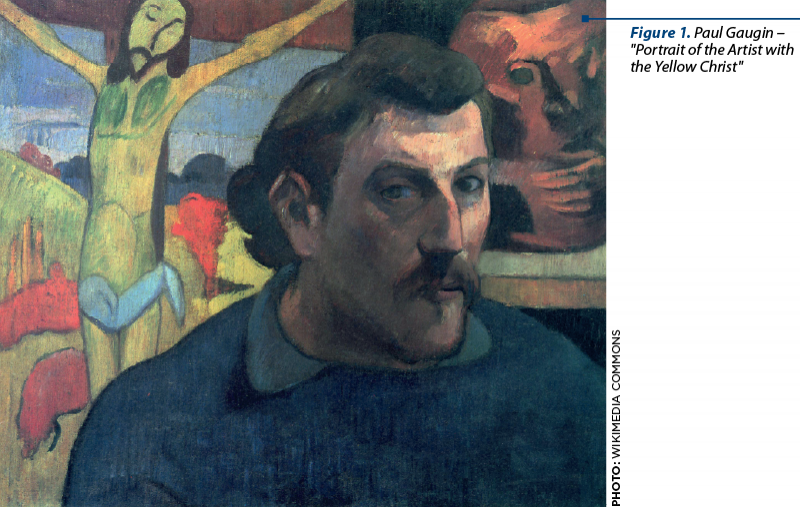

Many cases of genial artists, writers, painters, musicians are known to have ended their life by self-murder. Among these are: Van Gogh, Tchaikovsky, Jack London, Virginia Wolf, Ernest Hemingway, Ernest Kirchner, Cesare Pavese, and many others. To these, those with attempted suicide might be added: Gauguin, Schumann, E.A. Poe, O’Neill, Berlioz. There are also those with artistic works in which death constitutes a leitmotiv that crosses as a creepy incantation the whole creation: Novalis, Lautréamont, Chateaubriand, Camus.

The analysis of some artists’ life who died by suicide or who attempted a most lethal suicidal attempt imply the presumption of a real psychopathology.

Analyzing the production of the suicide, we note that all the aforementioned artists went through a phase of incubation of the suicidal motivation, a time in which the unfavorable conjecture and the decrease of the creative power crystalized on the mental plane in the idea of the necessity of the death.

The case of Gauguin

The life of Paul Gauguin constitutes a rich study material for psychiatrists. His personality, marked by unwontedness and nonconformism, triggered wonder and disapproval in his contemporaries(5).

As it happens many times in the case of art creators, the man stood many times hidden behind his official biography. Gauguin was an artist with a life full of exotism and mystery, that contributed to the creation of “the legend of Gauguin”, creating at first the anecdote about the man and only next, the understanding for the artist. The separation from the social traditions and ethical-moral bourgeois norms was many times thought as the sign of an alienated personality. Leaving his large family and a wealthy existence for a doubtful career of a painter, his adventurous travels in the Southern Seas and finding the paradise in the Oceania Islands received new interpretations in the actual vision. Of course, there were some psychopathological elements in the behavior and the thinking of the artist: extreme affective oscillations, megalomania, demonstrativeness, egocentrism, hedonist tendencies, poly-toxicophylia (alcohol, absinthe, opium). To that exalted nature, in balance between visionary enthusiasm and organic despair, the art acted as a regenerator medium. The consideration of all the factors that determined the structuring of this personality (childhood, family tradition, the educational process) brings new meanings in the explanation of “the myth of Gauguin”.

He spent his childhood in Lima, where the Gauguin family was in exile, living in the house of his uncle, a Peruvian statesman. He lived a wealthy life in an exotic and luxurious atmosphere. Returned to France, at the age of 15 years old, he embarked on different merchant ships, as a seaman and lately as an officer, and sailed to South America, Norway, Denmark and the Mediterranean Sea. After the death of his mother, he enters as a merchant agent in a bank from Paris, proving ability and know-how in business. For 12 years, he lived a conformist bourgeois life, proving ability and business skills. He married, the family life being rich and comfortable. Suddenly, he decided to leave the Stock Exchange to dedicate himself to painting. The family revenues decreased significantly, so that he separated from his wife and children whom he left in the care of the relatives. He goes many times in Bretagne, to look for new inspiration sources, unadulterated by conformism. He declared himself as a primitive nature and, wishing to break any link with the civilization, he wandered from Martinique Island to the Southern Seas, to Tahiti and Marquises Islands, where, being very ill, he died in 1903.

The biography of the artist has paradoxical dimensions; the fact of leaving the family, the financial situation, the honorable social position may be interpreted in a psychopathological but also in a vocational artistic sense(6).

The space covered in his journeys was only a recognition for himself that the concrete reality does not receive artistic life only by centralizing the data from utopic spaces(7). For a utopia of the type “the end of the world”, Tahiti Islands could offer a perfect scenario. Or, maybe the longing was broader: “The center of my art is in the brain, I create what is already inside myself”. In fact, what attracted Gauguin, regarding the way of life of the natives from Tahiti, was not the total freedom of feeling and action, but chiefly the landscape of some people where the fusion with the nature still existed: “You will always find the nourishing milk in the primitive arts. I doubt that you will find it in the art of mature civilizations”.

In a crash of his whole being in the precipice of despair, after hearing the news about the death of his son Clovis, he attempted suicide himself with arsenic. Being a long deliberated and premeditated act, he left for the posterity a painted testament: “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?”(8) In spite of the preparation measures for the suicide, by selecting of a powerful poison and also isolation measures, the painter was found by the natives and saved by them, through curing methods used in Polynesia.

However, he only lived shortly after this attempted suicide. He managed to paint several pictures after that. His consciousness as artist dictated the last conclusions of the adventures he passed through: “In any case, I did my duty and, even if my artwork will not survive, it will remain the memory of an artist that liberated the art of painting from academic bizarreness”.

The case of Jack London

The decay of the creative force made this writer to take the decision to commit suicide. He writes in one of his successful novels: “After we concluded our duties, when the vital force has exhausted, let’s exist the stage laughing”. Indeed, having chronic nephritis, when he felt that this moment came, Jack London committed suicide by concomitant ingestion of two powerful poisons. The suicide took place on his domain, being masked in the death certificate by the diagnosis of uremia.

The case of Robert Schumann

In this composer, the signs of a specific psychiatric disorder were present (progressive general paralysis), due to a luetic infection from the youth. During a melancholic raptus, he ran away from home, summarily dressed, and drowned himself into the Rhine, but he was rescued by some fishermen. Next, the depressive episode continuously evolved with a delirious and hallucinatory symptomatology, with musical hallucinations sometimes pleasant, sometimes terrific. The disorder debuted clinically in 1852, aggravated progressively, and the depressive states were accompanied by other alarming symptoms: lack of coordination of the moments, amnesia, dysarthria, so that this famous composer finded his end in 1856, in a dementia state. The attempted suicide, at the beginning of the illness, coincided with a moment of lucidity when he realized the severity of his illness.

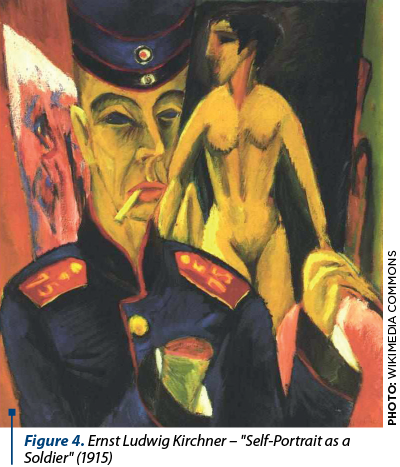

The case of Kirchner

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner is one of the most representative from the artistic current of expressionism, a current appeared in the German space at the beginning of the 20th century as a reaction to academic art constraints. The expressionists accentuated both the liberation of the body and also the exploration of the psychiatric with the gesture and the color. Their art liberated from the academic canons and it was frequently considered as a psychopathologic art(8).

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was born on the 6th of May 1880, in Aschafensburg, in a family from the high society. In conformity with the wishes of his father, he begins architecture studies at the Technical College from Dresden, but leaves soon for München and next to Nurnberg in order to study art. Longer visits to museums and art galleries confirmed the decision to become a perfectionist artist.

Back to Dresden in 1905, he founded the group Die Brücke, together with his friends Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rotruf, in order to revitalize the German art, suffocated by the academic tradition(9). The members of the group wanted to produce art so as to unite the rivers of the past and those of the future. Between 1907 and 1911, he discovered the hedonistic pleasures of plain free air, very popular in that period, passed on the river of the Moritzburg Lake, with his friends and their young models. The activity of the group culminated in 1909 with the big Exposition Die Brücke at the Richter Gallery in Berlin.

In the same year, he began to paint the night life from Dresden and Berlin, the cabaret, the dance, the theater, the prostitutes, being his favorite subjects in that period of life.

In 1910, the group left for Berlin, continuing to expose in the most important towns of Germany, but also in Moscow and Prague. The style of Kirchner evolved, specializing in the representation of the city life, with the cars, speed and agitated activity of the modern town. In 1912, he met Ema Schilling, whose he remained devoted to the end.

In 1913, some members of the group Die Brücke rebelled toward the authoritarianism of Kirchner, and soon after, the group dissolved.

During his Berlin years, in parallel with the plastic exploration of the German metropolis, Kirchner falls prey to regular and excessive alcohol consumption.

After the outbreak of the First World War, in 1915 he was obliged to fight as “involuntary volunteer” on the battle front. Not tolerating the soldierly discipline, he fell into a serious depression. He is dismissed, and send to rehabilitation at Taunus, and later at Davos, in Switzerland. In spite of his increasing dependence of morphine and alcohol, he achieves to create some of his most important works. He immortalizes the terrifying experience of the war in his painting “Self-portrait as a soldier”. He paints himself as mutilated, with the right hand being cut, a symbol of the creative power of the artist. At the same time, it is a picture with the role of confession, as in that life period, the depression and suicidal ideation that will have to put him down later, manifested with a great power. He continued to work on a farm in the Swiss Alps, as his health state improved.

In 1921, 50 of his works were exposed to Kronprinzen Palast in Berlin. The success of the exposition cemented his role of the leader of the expressionism.

Between 1925 and 1926 he came for the first time in Germany, after the Swiss exile. His reputation grew with the printing of the first monograph dedicated to his work, and due to another appearances in important magazines. In 1928, he participated to the Venice Biennale, that confirms his popularity among his compatriots. He begins to be known in the USA also.

In 1936, the Nazi power qualified the art of Kirchner as “decadent art” and confiscated all his works from the German museums, namely 369 paintings, causing him a great moral suffering. Furthermore, at the exhibition “Degenerate art” organized by the Nazi in München, 32 of his confiscated works were exposed. Among these, the painting “Selfportrait as a soldier” with a deliberate changed title as “Selfportrait with a whore” was exposed. All the exhibition cast disgrace on the efforts of the artists to find new forms of expression, with the aim to disavow the modern art and to qualify it as anti-patriotic. Even though he was in Switzerland, the disqualification of his art by the officials of the power produced in the artist a relapse of the illness, and threw him into a new depression. During this new depression, he destroyed a great amount of his works. After he “killed” the last created pictures, tired and exasperated by the political situation of Germany, on the 15th of June 1938, he ended his days, by shooting himself in the heart.

As an irony of destiny, the personal tragedy did not affect the international recognition of his artistic creation, his works being exposed in Detroit and New York with a great success.

Common traits of suicides

From the many aspects of the suicide, we retain the presence of 10 common traits described by Shneidman in The Definition of Suicide, found in all the categories of persons that committed the self-murderer act(9).

1. The common scope of the suicide is the search for a solution

The suicide is not a random act. It is never a needless or lacking scope act, but a way of solving a dilemma, a difficulty, a crisis situation. The suicide has an inherent, inexorable logic. It is, unfortunately, the unique available response to the question: “How shall I escape from this insupportable state?” The fear that narrows the spectrum of the answers leads to this unique variant.

2. The common scope of the suicide is the cessation of the consciousness

Ambivalently, the self-murderer evolves toward different targets at the same time. First, he wants to solve his problems, but concomitantly he thrives to stop the flux of consciousness.

3. The common stimulus in suicide is the intolerable psychological pain

The normal reaction of every individual is the tendency to avoid either the physical or the psychological pain. The enemy of life is the pain, and when it does not come from soma but from psyche, the psychological pain becomes a meta-pain, namely the pain to feel the pain.

4. The common stressor in suicide is represented by frustrated psychological needs

Every self-murderer considers the suicidal behavior as being very logical, derived from the conditioning imposed by the subjacent motivation.

5. The common feeling in suicide is of helplessness and despair

Unlike at the beginnings of the life, when the stimulation generated by curiosity and discovery is prevalent, the adult age brings with it the necessity of finding some life solutions, charged with responsibility. The appearance of the lack of hope, and of the feeling of helplessness derives from the too heavy burden that this responsibility charges on the person. The most common formulation of this feeling would be: “I cannot do nothing – except for suicide – and I do not find anybody to help me”.

If at the beginning of the century, the psychoanalytical theories explained suicide by aggressivity, respectively by retroprojected aggressivity or “crime at 180 degrees”, the contemporary suicidology considers that other abyssal emotions explain better the self-murder, such as: shame, guilt, despair, unaided dependence.

6. The common inner attitude in suicide is the ambivalence

“We can concomitantly to wish and to reject a thing”, said Freud. The prototype of the self-murder is that in which the subject cuts his throat and at the same time cries for help. The person of the self-murderer reunites in himself at least two tendencies: the self-destruction and the salvation planning.

7. The common cognition in suicide is the constriction

The suicide may be understood as a more or less durable narrowing of the affect and cognition. A “tunnelling”, a focus of the spectrum of options, that are generally available in the consciousness of the individual, is produced, as long as his thinking is not captured by the dichotomic gap of problem solving in conformity with the slogan “All or nothing!”.

8. Common action in suicide is the escape

The egression is the intentioned getting out by a person of a stressful situation, escape that has a different signification from flight, this one being a defense reaction. The suicide is a final egression, a stopping of the functioning of the real for the person concerned.

9. The interpersonal act is a communication of intent

In many cases of death by suicide, “the psychological autopsy” signalized clear indices of the acts that were to happen. The ambivalence of the self-murderer determines him to emit, consciously or not, despair, helplessness, panic signals and so on. “The suicide drama” is played by at least two characters, in a dyadic relation. It is sad to ascertain that the common interpersonal act of suicide is represented neither by hostility, nor by anger, but by an unsuccessful attempt to communicate with “the other”.

10. The common aspect of consequence in suicide is represented by the habitual reaction pattern of the individual

The suicidal behavior is in the continuity of the personality traits of the self-murderer. The same steadfastness of the inability to solve the life problems, of the habit to react to stress in an inadequate way, is found. At an attentive scrutiny, these traits may be deciphered since the adolescence or youth of the self-murderer. Cesare Pavese(10) noticed since his first youth, at 20 years old, in his journal: “No more words. Just the deed… I will cease to write!”.