The concern of long-term psychological and social consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic arises, as we have been experiencing more than a year of global exposure to the virus, virus-related health issues and varying containment measures. Assumptions regarding the negative outcomes and groups at higher risk for such outcomes require relevant scientific evidence, global scale studies and the test of time. Nevertheless, the body of data thus far proves that COVID-19 is a global issue and it requires coordinated, global-scale management. Moreover, trauma-informed practice emerges as a requirement of effective health policies and patient management during and after the pandemic. The current paper focuses on the specific issue of COVID-19 exposure as traumatic experience. We aim to outline definitions of trauma/traumatic events, emphasize that exposure to trauma is not an illness per se, but it increases the risk of health issues, ascertain why the COVID-19 exposure can be viewed as a traumatic event with potential detrimental consequences for the biopsychosocial health of persons and communities. We also aim to describe specific groups with increased vulnerability for detrimental mental health outcomes in the context of COVID-19 exposure, along with the nature of the vulnerability and proposed preventive measures for better mental health outcomes in higher-risk groups.

Trauma psihică a expunerii la infecţia cu SARS-CoV-2

The psychological trauma of COVID-19 exposure

First published: 18 aprilie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.65.2.2021.4971

Abstract

Rezumat

După mai mult de un an de expunere globală la COVID-19, la consecinţele acesteia asupra stării de sănătate şi la măsuri variabile de limitare a răspândirii SARS-CoV-2, ne confruntăm cu perspectiva consecinţelor psihologice şi sociale negative pe termen lung ale pandemiei de COVID-19. Ipotezele privind consecinţele negative ale expunerii şi grupurile populaţionale la risc crescut necesită evidenţe ştiinţifice riguroase, studii de anvergură globală şi testul timpului. Dovezile ştiinţifice actuale susţin că pandemia de COVID-19 este o problemă de sănătate publică globală ce necesită măsuri globale coordonate de management. Mai mult, se dovedeşte tot mai necesară includerea evaluării traumelor psihologice atât în politicile de sănătate, cât şi în practica uzuală clinică din pandemie şi ulterior. Articolul abordează expunerea la COVID-19 ca experienţă psihotraumatizantă, urmăreşte definirea traumei/evenimentului traumatizant, accentuează că expunerea la traumă nu este în sine patologică, dar creşte riscul pentru probleme de sănătate şi detaliază de ce expunerea la COVID-19 poate fi privită ca eveniment traumatizant, cu consecinţe negative pentru sănătatea biopsihosocială a persoanei şi a comunităţilor. De asemenea, articolul descrie grupele cu vulnerabilitate crescută pentru consecinţe negative pentru sănătatea mintală după expunerea la SARS-CoV-2, precum şi natura vulnerabilităţilor şi măsuri preventive pentru ameliorarea prognosticului pentru sănătatea mintală a grupelor de risc.

The exposure to psychological trauma is a process which intertwines with other ongoing individual and community processes: individual and community growth, development and history, social and cultural changes, individual and family history of illness, illness process. The exposure to trauma as a process is influenced by a myriad of known and mostly unknown factors and their uncertain dynamic entanglement. The exposure to trauma is neither an illness per se, nor a factor that generates illness in all persons exposed; nevertheless, it increases the risk for illness of those exposed and contributes to: vulnerability for illness, illness onset, exacerbation, recurrence and relapse, protracted illness duration, increased symptom severity, barriers to care and overall poorer physical, psychological and social illness outcomes(1).

The studies propose a practical definition of psychological trauma(2) which encompasses the following features (i.e., the four “E”s):

1) Event – any untoward occurence that poses actual and/or potential objective danger to one’s life and integrity.

2) Experience – a wide range of subjective, individual experiences that share the core symptoms of arousal, intrusive reexperiencing and avoidance of traumatic cues.

3) Effects – uncertain, individual physical, psychological and social consequences that conflate within a longer-term process of readjustment to life after trauma.

4) Evolution – life-long process with individual outcomes significantly influenced by the individual peritraumatic experience, available support and timely access to support.

COVID-19 entails a number of characteristics which underscore its relevance as a global-scale traumatic event generating psychological trauma. Firstly, COVID-19 is an ongoing global event, a complicated health, psychological and social crisis. Secondly, the ability to control the course of the pandemic is perceived as very limited. Moreover, there are no relatively recent events, similar in magnitude and evolution, which might inform the management of the pandemic. Also, the pandemic emerges in a context where the assessment of exposure to psychological trauma and integration of trauma-related issues in the individual management plan (trauma-informed practice) were not part of the current practice. This in turn affects the management of the pandemic due to delays in ascertaining of, and catering to unmet patient needs generated by the exposure to trauma(3).

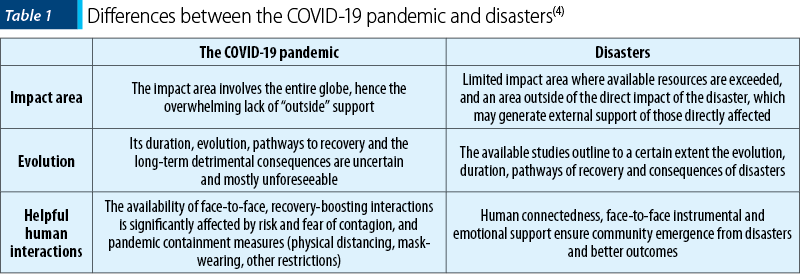

The COVID-19 pandemic, albeit its collective, shockwave nature, ostensibly differs from natural or other disasters, as presented in Table 1(4).

As previously outlined, the exposure to COVID-19 does not generate illness in general, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in particular, in all persons exposed(1,4). Nevertheless, COVID-19 incurs important immediate psychological consequences(4), as follows:

Persons with preexisting mental health issues experience a worsening of their condition.

Persons with risk factors for mental health issues (depression, anxiety, addiction) experience the onset of symptoms of these disorders.

Symptoms of PTSD develop, ranging from transient ones to complex PTSD.

Studies report that 23 to 34 percent of those exposed to the trauma of COVID-19 develop PTSD symptoms(5). Some – if not most persons exposed – will experience COVID-19 as a complex traumatic event, due to the intricate repetitive, protracted nature of exposure to the event. Moreover, barriers in the access to care during the pandemic, the experience of illness while physically distanced from the loved ones, the failure to be physically present for the loved ones who are going through illness add to the complex trauma features of COVID-19(4). Therefore, a complex PTSD diagnosis may be warranted in persons who describe PTSD symptoms, significant distress and impaired functioning in the context of COVID-19 exposure. Complex PTSD entails poorer quality of life, more resources required in treatment, poorer outcomes for the persons and their context(6).

The social consequences of COVID-19 entail:

-

Social isolation(7), disrupted daily schedule, routines and habits, with increased pressure to develop new routines quickly(4).

-

Temporary/permanent income loss(4).

-

Impaired social support system (family, friends)(8).

-

Increased risk of domestic violence, child and partner abuse, due to pressures of confinement with abusive family, limited access to community support(9-11).

-

Limited access to social services, school and education(4).

-

Increased social and health inequities due to the widening gap in access to work, social services, healthcare and other community resources(12,13).

-

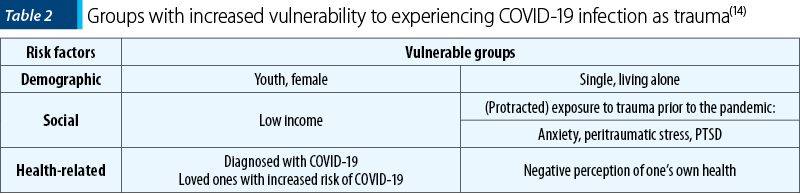

A growing body of evidence supports that specific groups are more vulnerable to the psychological trauma nature of COVID-19 infection – Table 2(14).

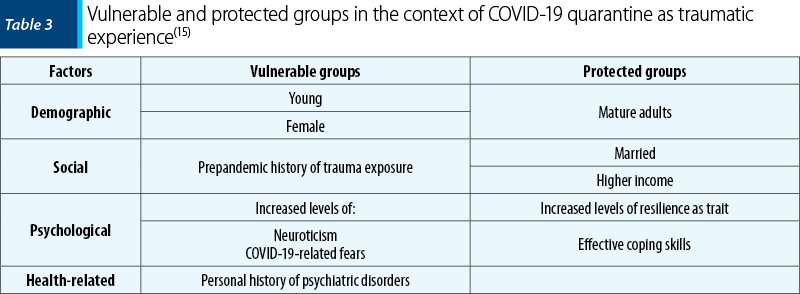

Quarantine placement measures for COVID-19 containment may emerge as distinctive traumatic experience. Specific populations are more vulnerable to this type of trauma, while others are protected – Table 3. Moreover, the intensity of reported psychiatric symptoms, not their type (phobia, anxiety, depression, stress, obsessions, compulsions, hostility), mediate the association between individual personality traits and the degree of vulnerability to the trauma of quarantine placement(15). Among reported cognitive symptoms, ruminations paired with perceived controlability may generate poorer, potentially fatal outcomes due to increased risk for suicidal behaviours(16).

Patients treated in the intensive care units (ICUs) during COVID-19 and their loved ones exhibit specific vulnerabilities for psychological trauma. Due to patient’s separation from loved ones, both patients and loved ones miss the opportunities for:

-

hospital visits, face-to-face connection, support and care

-

first-hand experiences of the efforts of the medical team to care for the patient

-

effective connection and partnership of patient, loved ones and medical team for treatment and recovery(17).

Furthermore, the uncertainty, unpredictability, unexpected quick changes in patient's health status, the limited and physically distanced communication between medical team and the loved ones of ICU patients affect the medical decision-making algorhythms for the management of ICU patients during the pandemic(17). Additionally, COVID-19 incurs severe disruption in the process of end-of-life care, loss and grief(18).

The traumatic experience of COVID-19 for the person who works as medical staff comprises the traumatic experience on a personal level, added to the compassion fatigue in the medical staff role, generated by burnout and secondary trauma (witnessing the patient’s trauma). More specifically, the medical staff who treat COVID-19 patients exhibit significantly higher levels of stress, anxiety, depression, burnout, secondary trauma, while the medical staff working in areas with higher rates of COVID-19 sustain a major risk of stress, burnout and compassion fatigue. Therefore, ongoing active psychological support of medical staff ensures higher quality healthcare services that are better tailored to the pandemic context(19).

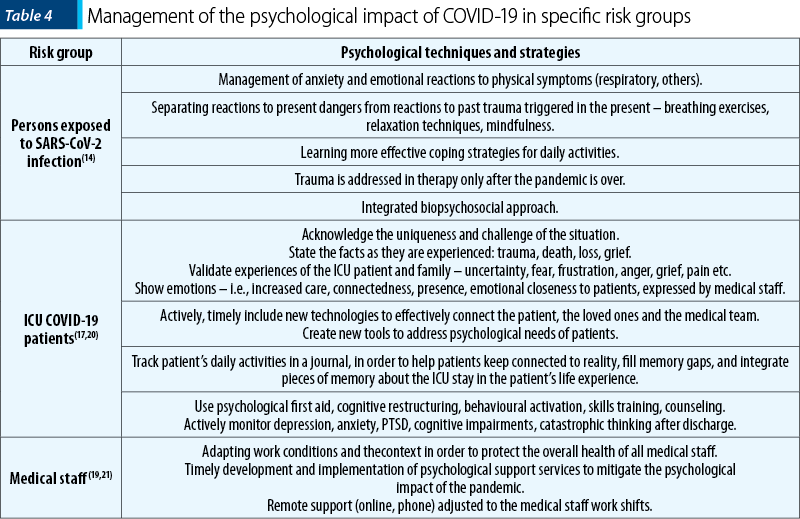

Mitigating the traumatic impact of COVID-19 exposure requires strategies that are both globally integrated, and specifically tailored to meet the evolving needs and address the unforeseen consequences of the pandemic in persons and communities(3). Specific strategies for some groups at risk for psychological trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic are outlined in Table 4.

Ongoing studies will further elicit insight into risk and vulnerability factors for the traumatic experience of COVID-19. Nevertheless, integrated biopsychosocial trauma-informed response comprised of the following four “S”s is the cornerstone of the effective management of resources in the context of the pandemic(2):

1) Safety – providing a safe environment for the exposed person.

2) Support – actively bringing available support closer to the person and creating new resources for the emerging needs.

3) Sensitivity – culturally sensitive and specific support.

4) Screening – active assessment of the trauma experience and consequences of trauma exposure, for a timely and more effective intervention targeting most vulnerable persons.

Bibliografie

- Herţa DC. Tulburarea de stres posttraumatic – provocări şi priorităţi.

- Psihiatru.ro. 2017:48(1);21-5.

- Griffin G. Defining trauma and a trauma-informed COVID-19 response. Psychological Trauma. 2020;12(S1);S279-80.

- Horesh D, Brown AD. Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19. Psychological Trauma. 2020;12(4);331-5.

- Osofsky JD, Osofsky HJ, Mamon LY. Psychological and social impact of COVID-19. Psychological Trauma. 2020;12(5);468-9.

- Qiu D, Li Y, Li L, He J, Ouyang F, Xiao S. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms among people influenced by coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: A meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2021 Apr 12;64(1):e30.

- Jowett S, Karatzias T, Shevlin M, Albert I. Differentiating symptom profiles of ICD-11 PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder: A latent class analysis in a multiply traumatized sample. Personal Disord. 2020 Jan;11(1):36-45.

- Smith BJ, Lim MH. How the COVID-19 pandemic is focusing attention on loneliness and social isolation. Public Health Res Pract. 2020 Jun 30;30(2):3022008.

- Prime H, Wade M, Browne DT. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol. 2020 Jul-Aug;75(5):631-643.

- Mazza M, Marano G, Lai C, Janiri L, Sani G. Danger in danger: Interpersonal violence during COVID-19 quarantine. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Jul;289:113046.

- Moreira DN, Pinto da Costa M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the precipitation of intimate partner violence. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2020 Jul-Aug;71:101606.

- Pereda N, Díaz-Faes DA. Family violence against children in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic: a review of current perspectives and risk factors. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020 Oct 20;14:40.

- Krouse HJ. COVID-19 and the Widening Gap in Health Inequity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 Jul;163(1):65-66.

- Gray DM 2nd, Anyane-Yeboa A, Balzora S, Issaka RB, May FP. COVID-19 and the other pandemic: populations made vulnerable by systemic inequity. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Sep;17(9):520-522.

- Lahav Y. Psychological distress related to COVID-19 – The contribution of continuous traumatic stress. J Affect Disord. 2020 Dec 1;277:129-137.

- Rogers ML, Gorday JY, Joiner TE. Examination of characteristics of ruminative thinking as unique predictors of suicide-related outcomes. J Psychiatr Res. 2021 May 7;139:1-7.

- Fernández RS, Crivelli L, Guimet NM, Allegri RF, Pedreira ME. Psychological distress associated with COVID-19 quarantine: Latent profile analysis, outcome prediction and mediation analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020 Dec 1;277:75-84.

- Montauk TR, Kuhl EA. COVID-related family separation and trauma in the intensive care unit. Psychological Trauma. 2020;12(S);S96-7.

- Feder S, Smith D, Griffin H, Shreve ST, Kinder D, Kutney-Lee A, Ersek M. “Why Couldn’t I Go in To See Him?” Bereaved Families’ Perceptions of End-of-Life Communication During COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021 Mar;69(3):587-592.

- Trumello C, Bramanti SM, Ballarotto G, Candelori C, Cerniglia L, Cimino S, Crudele M, Lombardi L, Pignataro S, Viceconti ML, Babore A. Psychological Adjustment of Healthcare Workers in Italy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Differences in Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Burnout, Secondary Trauma, and Compassion Satisfaction between Frontline and Non-Frontline Professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Nov 12;17(22):8358.

- Tingey JL, Bentley JA. COVID-19: Understanding and mitigating trauma in ICU survivors. Psychological Trauma. 2020;12(S1);S100-4.

- Lefèvre H, Stheneur C, Cardin C, Fourcade L, Fourmaux C, Tordjman E, Touati M, Voisard F, Minassian S, Chaste P, Moro MR, Lachal J. The Bulle: Support and Prevention of Psychological Decompensation of Health Care Workers During the Trauma of the COVID-19 Epidemic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021 Feb;61(2):416-422.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Internările consumatorilor de droguri în spitalele de psihiatrie din România (2018-2021)

Substanţele psihoactive reprezintă o problemă importantă de sănătate publică, în special ţinând cont de trendul ascendent al numărului de cazuri di...

Accesul populaţiei din România la îngrijiri de sănătate mintală în timpul pandemiei de COVID-19

Contextul nou apărut atât în România, cât şi pe plan mondial – pandemia de COVID-19 – a pus la încercare sistemul medical la nivelul tuturor ţărilo...

Centralitatea pandemiei de COVID-19 ca eveniment traumatizant la studenţii medicinişti

Impactul psihologic negativ al pandemiei de COVID-19 este mai intens la tineri, la sexul feminin, la persoane singure (ca statut partenerial), cu a...

Coping mechanisms of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on all aspects of life, causing significant psychological distress. Individuals had to make major chang...