Craniocerebral trauma requires a multidisciplinary approach, due to the impact on the neurological and psychiatric sphere, being a major public health problem because of the disability produced. This paper presents the case of a patient with neurological and psychiatric disorder triggered by a craniocerebral trauma, who required a multidimensional approach and received repeated medical care in the specialties of neurosurgery, neurology, oral and maxillofacial surgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation and psychiatry.

Tulburări psihice asociate traumatismului craniocerebral

Psychiatric disorders associated with craniocerebral trauma

First published: 18 aprilie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.65.2.2021.4997

Abstract

Rezumat

Traumatismul craniocerebral necesită o abordare pluridisciplinară, în urma afectării din sfera neurologică şi psihiatrică, fiind o problemă majoră de sănătate publică, din cauza dizabilităţii produse. Această lucrare prezintă cazul unui pacient cu afectare neurologică şi psihiatrică apărută în urma unui traumatism craniocerebral şi care a necesitat o abordare multidimensională, primind îngrijiri medicale repetate în specialităţile neurochirurgie, neurologie, chirurgie buco-maxilo-facială, medicină fizică şi reabilitare şi psihiatrie.

Introduction

Polytrauma ranks third worldwide among the general causes of mortality after cardiovascular and oncological pathology. Forty percent of injuries have a canioencephalic component. Craniocerebral trauma, a public health problem, requires a multidisciplinary approach by involving neurosurgery, neurology, oral and maxillofacial surgery, physical and rehabilitation medicine and, last but not least, psychiatry. Through the neurological and psychiatric changes that they cause, craniocerebral traumas are the most important cause of disability(1-3).

In addition to neurological effects, craniocerebral trauma can cause immediate and late psychic manifestations(4,5).

The case presented describes a complex neuropsychiatric scenery requiring a multidisciplinary approach (neurosurgery, neurology, oral and maxillofacial surgery, physical and rehabilitation medicine and psychiatry), with hallucinatory-delusional symptoms, as well as behavioral and personality changes, having major implications on the patient’s life, leading to social, relational, functional and even legal consequences.

The patient M.A. is 35 years old, male, domiciled in rural areas, divorced, with two children, with secondary education, and no occupation.

Circumstances of hospitalization

The patient has a psychiatric and neurological history, being hospitalized in the emergency unit, brought by ambulance from the Neurology Service of the Clinical Hospital of Sibiu County, on July 14, 2020, for a psychopathological symptomatology manifested by: psychomotor agitation, confusion, irritability, disorganized behavior and hypnotic disorders, symptoms after an epileptic status, during grand mal posttraumatic epilepsy.

Family medical history

The father – chronic consumer of ethanol.

The younger brother was admitted to psychiatry.

Pathological personal history

January 2016: admitted to the neurosurgery department for craniocerebral trauma after falling off the scaffold (10 m height), causing fracture of the left frontal bone with displacement, fracture of the molar bone and jaw bones, bilateral fracture of the temporal-zygomatic arch with the bone pushed inside, fracture on the third distal left radius, right iliopubic fracture.

February 2016: admitted to orthopedics – fracture in the third distal left radius, and right iliopubic fracture.

February 2016: admitted to oral-maxillofacial surgery service. Fracture of the molar bone and jaw bones, bilateral fracture of the temporal-zygomatic arch with the bone pushed inside.

February 2016: admitted for medical rehabilitation.

May 2016: admitted to psychiatry – organic psychotic disorder.

October 2017: admitted to psychiatry – organic psychotic disorder, sequelae following frontal cranial trauma.

April 2018: admitted to neurology – posttraumatic epilepsy with grand mal seizures, posttraumatic encephalopathy, sequelae after frontal cranial trauma.

November 2018: admitted to psychiatry – organic delusional disorder, posttraumatic epilepsy with grand mal seizures, posttraumatic encephalopathy, sequelae after frontal cranial trauma.

September 2019: admitted to neurosurgery – fracture without displacement of the lower articular facet C7, posttraumatic epilepsy with grand mal seizures, posttraumatic encephalopathy, sequelae after frontal cranial trauma, organic delusional disorder.

July 2020: admitted to neurology – Anesthesia and Intensive Care Unit – posttraumatic epilepsy with grand mal seizures, posttraumatic encephalopathy, sequelae after frontal cranial trauma, organic delusional disorder.

Elements of psycho-sociogenesis: living and working conditions

From the patient’s life history, we retain that he comes from a disorganized family, with precarious material conditions. He was born in Hungary, to a Hungarian father and a Romanian mother. They moved to Romania when he was 2 years old. He is the third born among 10 siblings (3 boys and 7 girls). In 1993, when the patient was 8 years old, his parents decided to separate, without attempting a divorce, the mother moving with all 10 children to Oltenia region, to the grandparents’ house. The father used to visit them, he took the boys with him to work (“From the age of 10, my father took me with him and taught me how to make cement, plaster. Only the skillful knows that plaster also has to be sifted”). But he also used to take their money, including those on child allowances, to buy himself alcohol. The patient remembers that the father used to beat him and his older brother (“He took the ax, the hatchet, whatever was at hand, and threw at us with it”). The mother worked as an employed tailoress and, thanks to her, he learned to sew.

The patient says that he had a “difficult” childhood, without financial possibilities. He had a good relationship with his siblings, feeling obliged to protect his sisters. He states that he was a “peaceful, good-natured, obedient boy, he did not seek scandal and did not fight with boys. Only when they played football did they get upset and argued”. He liked to play football, having the role of coach or attacker. He began his sexual life at the age of 12, having unprotected sexual contact with multiple partners (“Girls always made a move on me, wherever I went. Even now they do it, but I ignore them”).

At school, he had good results, even very good ones, receiving awards. He finished high school in construction, the interior-exterior finish being the field he is passionate about and his domain of expertise.

At the age of 28, he got his first contract employment in construction, until then earning a living as a day laborer in agriculture.

At the age of 19, he married out of love, taking his wife’s name “because that’s what I saw my older brother did and I thought that this way I would have a happy marriage like his”. Before marriage he practiced two years of judo, four years of boxing and three years of karate, but at the insistence of his wife, he gave up training. He wanted many children, but his wife told him that “we will have them one by one, because we don’t have a place to live, we don’t have enough money to take care of them, and other nonsense”. He has been living alone for four years after his wife left him together with his two children (two boys, aged 14 and 12, respectively), the reason being that the patient started consuming larger amounts of alcohol, although she also “liked drinking”. He says he loves his wife and children very much and, although she has cheated on him countless times, he wants them to be together again. The two spouses only talk on the phone, she always telling him that she does not want to reconcile and, rarely, she allows the children to talk to him, at which point they tell him that “they miss him, that he is the best father”.

Although the patient prefers to offer this beautifully outlined picture of his family, we find out from the heteroanamnesis that the divorce was pronounced, the wife obtaining the house where they lived and the guardianship of the children, and the rest of the family does not want to know anything about the patient, much less to take him home and take care of him, the father being the one who denies him as a biological son.

Toxic habits

Smoking: approximately 10 cigarettes with filter/day.

Alcohol: former chronic consumer of ethanol (the heteroanamnesis shows 300-400 ml distilled alcohol per day, in the last year), currently abstinent (14 days) – admission to the neurology service (AICU; July 1, 2020).

Background medication administered prior to hospitalization

Patient intermittently treated (anticonvulsant and antipsychotic), abandoning the treatment about 2-3 months after discharge.

Antipsychotic and anticonvulsant treatment taken from July 1, 2020, after the admission to the neurology service – AICU.

History of the disease

In January 2016, the patient suffered a fall at work, from a scaffolding, from a height of 10 meters, resulting in multiple fractures, both in the head and extremities, therefore he was hospitalized in the neurosurgery service (January 13, 2016) in deep coma (Glasgow score = 5), with equal pupils, intubated and mechanically ventilated. Locally, the patient had a large frontal, parasagittal wound of about 10-12 cm, with textile material embedded in it, which macroscopically went deep. Emergency surgery was carried out and an osteotomy was performed, with the foreign body removed from the dura mater (injured dura mater). The neurological evolution was good, the patient opening his eyes and remaining with a motor deficit in the right hemibody.

Cranial CT – extradural hematoma, for which bone flap was carried out, using the sides of the linear cranial fracture and the extradural hematoma was evacuated.

After this intervention, the evolution was good, both clinically and paraclinically, the patient being aware, with the motor deficit in improvement, and began to say a few words.

The case was transferred to the orthopedics service (February 1, 2016), where the following diagnoses were established: distal-third fracture of the left radius and right iliopubic fracture. Surgery was carried out to perform the osteosynthesis of the left radius, under general anesthesia and orotracheal intubation, using a plate and seven screws. The evolution was favorable under antibiotic, analgesic, antithrombotic and muscle relaxant treatment.

Radiography – good focus of the fracture site with clean wound, no secretions, healing. The patient was transferred to the OMF service (February 5, 2016), where the following diagnoses were established: comminuted fracture with the anterior wall of the left maxillary sinus pushed inside, fracture of the posterior wall of the left maxillary sinus, displaced fracture of the frontal bone, left malar bone disjunction, with displaced fractures of the left infraorbital rim, displaced fracture of the left frontal zygomatic arch, displaced fracture of the left temporal-zygomatic arch, blocking fracture of the right temporal-zygomatic arch. The patient underwent surgery on February 6, 2016, practicing open reduction and immobilization by osteosynthesis of the fracture of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus and left supraorbital rim, with titanium tent fixed with six screws and osteosynthesis plate fixed with four screws. The postsurgery evolution was favorable under treatment with antibiotic, analgesic, antithrombotic and antiinflammatory medication. The toilet of the postsurgery frontal wound was performed daily with weakly antiseptic solutions and sterile dressing.

Cranial CT (February 17, 2016) – left orbitofrontal epidural hematoma almost completely resorbed and left orbitofrontal reconstructive osteosynthesis. Discharged on February 18, 2016, in good general condition; postoperative wound without signs of dehiscence in the process of healing, partially cooperative, stable cardiorespiratory and hemodynamic.

The patient was admitted to the Medical Rehabilitation 2 Department (February 29, 2016) for physiotherapeutic treatment. Clinically, he had a hypomobile left elbow, a coxofemoral joint with slightly diminished abduction, a slightly ataxic gait, with a wide support base. During hospitalization, the patient had episodes of delirium and hallucinations, for which psychiatric consultation was recommended, haloperidol solution 3-3-7 drops/day being recommended.

The patient came to psychiatry with a referral note from the family physician (May 6, 2016), being hospitalized for a new psychotic decompensation (diagnosis: organic psychotic disorder), due to noncompliance to treatment. At the time of admission, the patient had delusional paranoid ideation (shadowing, persecution, injury), possible auditory hallucinations deduced from behavior (soliloquy), hallucinatory-delusional behavior, psychomotor anxiety, irritability, impulsivity, mixed insomnia. He remained hospitalized for 10 days, being given treatment with antipsychotic (risperidone 1 mg 1/2 -1/2-2 tb/day), mood stabilizer (Depakine® 300 mg 1-1-1 tb/day), anxiolytic (Rivotril® 0.5 mg 1-1 -1 tb/day), vitamin B therapy, nootropic (Cerebrolysin® 1 ampoule/day), the evolution being favorable, with behavior improvement and the disappearance of the psychoproductivity elements.

The patient was hospitalized in an emergency unit of the Psychiatry Hospital (October 5, 2017), the symptoms being as follows: psychoemotional lability, delusional ideas of injury, temporospatial disorientation, mnemonic and prosexic disorders, circumstance, low tolerance to frustration and friction. He was treated with Depakine® 500 mg 1-1-1 tb/day, risperidone 4 mg 1-0-1/2 tb/day, Rivotril® 0.5 mg 1-0-1 tb/day, the evolution being favorable.

Following this accident and the extended duration of the hospitalization, the patient’s employer was sued, having to pay him, as compensation, a considerable amount of money and offered him a house, the goods being registered on the names of both spouses, and later lost by the patient following the divorce action.

As a result of the long hospitalization, the patient acquired the right to be retired on medical grounds, the inability to operate and make decisions being found following the forensic psychiatric expertise that was performed during the trial with the employer – work accident. Also, the psychiatric forensic expertise established that the patient had diminished judgment.

The patient was transferred from the Emergency Admission Unit of Sibiu to the Neurology Department (April 18, 2018) in postcritical condition after generalized tonic-clonic seizures. At the time of presentation, the patient had postcritical drowsiness alternating with periods of psychomotor agitation, equal, symmetrical osteotendinous reflexes, without motor deficit and without coordination disorders. During the hospitalization, he did not present any more seizures, he regained his state of consciousness and left the hospital, contrary to the medical opinion, before performing the complete assessment.

The patient was admitted to the Emergency Admission Unit of Sibiu (23.11.2018) for a new tonic-clonic seizure, associated with a confusional syndrome. Following the investigations, a psychiatric consultation was considered necessary, the patient remaining hospitalized for the third time in the psychiatry service (November 24, 2018), with a clinical scenery manifested by: temporospatial disorientation, psychomotor anxiety alternating with drowsiness, mnemonic and prosexic disorders, echolalia, viscosity of thoughts. Diagnosis: organic delusional disorder, posttraumatic epilepsy with grand mal seizures, posttraumatic encephalopathy, sequelae following frontal cranial trauma. During the interaction, the patient underwent:

-

laboratory tests – do not indicate pathological changes;

-

psychological examination – cognitive functions with diminished efficiency, disorders of judgment and reasoning, fragmentary ideas in the paranoid sphere, slow comprehension, difficulty in attention focus. Indices of organicity in the sphere of personality: emotional lability, poor impulse control, bizarre behavior;

-

EEG – EEG path with an α background rate of 9-10 cycles/second, left-right interhemispheric asymmetry, spontaneously enrolling in slow D-band waves in the left anterior frontal-temporal derivations.

The patient suffered a new fall, resulting in loss of consciousness and trauma to the cervical spine. At the time of admission to the neurosurgery section (September 18, 2019), the patient was conscious, cooperative, temporally and spatially oriented, with a dizzying and headache syndrome, no sensitivity or motility disorders, no signs of intracranial hypertension, praxis, lexis and gnosis within normal limits. In a clinical and imaging context, there was no operative indication, and at the time of discharge the patient’s condition improved.

The onset of the current episode of the disease was sudden: the patient was brought to the neurology service (July 1, 2020), by the County Ambulance Service crew, in epileptic status, due to medication nonadherence. At the time of examination in the EAU, the patient was applied orotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, being continuously sedated with Dormicum®. The general and neurological examination in EAU revealed a comatose patient (GCS=3), febrile (T=38.4oC), with dehydrated skin and mucous membranes, with cracking right basal crackles, uro-bladder probe, flaccid tetraplegia, intermediate pupils, weakly reactive to light osteotendinous reflexes abolished globally, plantar skin reflex in bilateral extension.

Laboratory tests performed at admission revealed hyperamylasemia, nitrogen retention syndrome, neutrophil leukocytosis and lymphopenia.

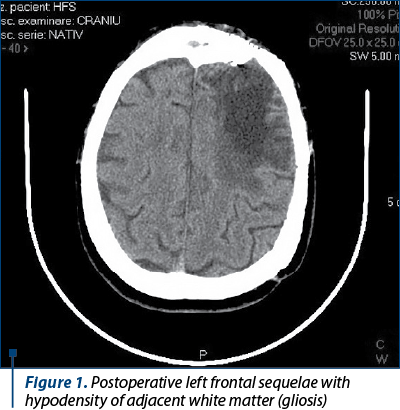

Cranial CT (Figure 1) – postoperative left frontal sequelae with hypodensity of adjacent white matter (gliosis).

Chest CT – without posttraumatic injuries on cervical spine, segmental condensation areas, bilateral LI, LM associated in the right with peribronchovascular micronodules; infectious process/aspiration, with endobronchial involvement.

EEG with 21 electrodes placed on the scalp, in a 10-20 system. During the monitoring, slow dysrhythmia of the theta-delta intermittent left frontotemporal side was shown, with the presence of rare epileptiform elements (sharp waves in the same derivations).

During the hospitalization in the neurology service, Anesthesia and Intensive Care Unit, the patient was applied orotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, and was continuously sedated with propofol and fentanyl and carbamazepine was administered by nasogastric tube 3x1 tb/day and levetiracetam by injections – two ampoules in 50 ml saline solution, with an administration rate of 2 ml/h. On July 9, 2020, the patient was detubated, had spontaneous breathing, was conscious, cooperative, without epileptic seizures.

The transfer of the patient to the neurology service was requested (July 10, 2020). At the time the patient was taken over, he presented spastic tetraparesis, vivid global osteotendinous reflexes, bilateral plantar skin reflexes in extension, coordination within normal limits, right sequelous superficial hemihypoaesthesia, without epileptic seizures, bilateral calcaneal eschar with flictenas at the right calcaneus, right elbow escarpment with blood crust and erythematous lesion in the right arm, left hip eschar, and subfebrile (T=37.3oC). During the hospitalization, the patient presented visual hallucinations, psychomotor agitation, requiring restraint and sedation, therefore he was transferred to the psychiatry section (July 14, 2020).

Somatic examination

Good general condition, pale, sweaty skin, left forearm scars, left frontoparietal scar after cranial trauma, with deformation of the cranial box. Objective examination on devices and systems reveals: cranial nerves – normal relations, negative paresis tests, more vivid osteotendinous reflexes on the right, unresponsive bilateral plantar skin reflexes, without sensitivity or coordination disorders, walking is possible without support. Blood pressure = 135/90 mmHg, Ventricular rate = 69 bpm.

Psychiatric examination

Mimicry is mobile, with wide gestures, keeping eye contact, staring and rarely blinking. The outfit is hospital-like. The attitude is cooperative, with inadequate familiarity, hostility, interpretability and suggestibility. Verbal contact is possible, with relatively effective speech, mild bradylalia, high latency in responses, with speech precipitation when sensitive subjects appear. The patient has insight into the neurological disease, he has no insight into the mental disorder, presenting elements of the oneiroid syndrome (“The Virgin Mary and Jesus always appear in my dream and tell me that I will be well. I am the proof of God’s power”).

The patient is correctly self-oriented and allopsychic, but disoriented temporally and spatially. There is a spontaneous and voluntary deficit of attention, as well as hypomnesia of fixation and evocation of mild intensity, after an amnestic gap during epileptic status.

In the relation to perception, there is an auditory hyperesthesia (the patient is disturbed by the doorbell, by the noise made by the rest of the patients in the wards), with possible auditory and visual hallucinations deduced from the behavior, false acknowledgments (the patient complains of two nurses, although they see him for the first time).

The thinking is coherent, with bradypsychia, and ideation centered on the sociofamilial situation, filling the memory gaps with conspiracies, capacity for abstraction, generalization, diminished analysis and synthesis, poor mental calculation, low judgment and reasoning. There is also a delusional idea of grandeur (“My father was the best, he bought us everything we wanted. My brother also buys me what I want, bicycle, motorcycle. All women make a move on me, even you, but you don’t want to say it”), mysticism (“I am the divine miracle, through me God showed His power”, “You are Judah on earth”), and a suicidal, fleeting, unplanned ideation (“I want to I take my life, but I dreamed of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ who told me to take the pills and be good because everything will be fine”).

The executive function is diminished by the patient’s inability to take information correctly, to organize and plan his behavior, and by poor impulse control.

The language is simple, giving answers with high latency; the patient also presents aggression, when the tone of voice is increased and becomes threatening.

Affectivity: highly agitated general mood with ego hyperinflation, intricate exaggerated self-esteem with emotional lability, poor emotional modulation with irritability and low tolerance to frustration.

Willpower and voluntary activity: poor control of behavior and impulses, with untimely APM states, with disorganized behavior, with acting out phenomena (“I feel that my memory hurts and then I start punching myself in the head”; during the interview, the patient raises his fist, has a high pitch of voice, threatening), potentially hostile and unpredictable behaviors.

Instincts: sexual – exaggerated sexual preoccupations (“Although I can have any woman I want, I have never cheated on my wife and I only want her”), with behavior inhibition; defense – exacerbated.

Personality with organic epileptic indices.

Paraclinical explorations

-

Laboratory tests – do not indicate pathological changes.

-

EKG – sinus rhythm, ventricular rate = 69 bpm.

-

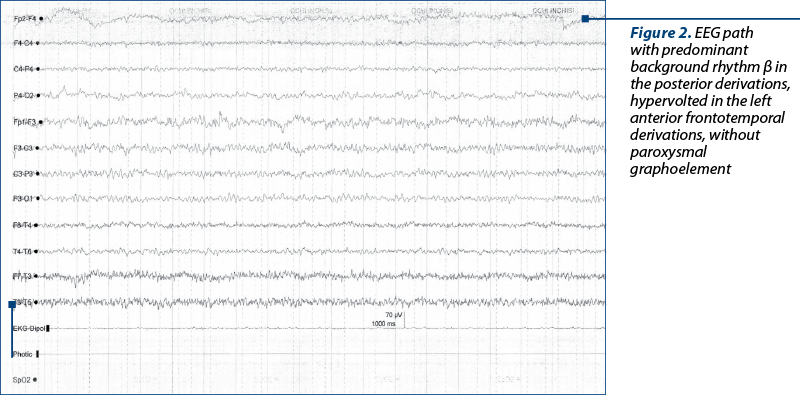

EEG (Figure 2): route with predominantly β background rhythm in the posterior derivations, hypervolted in the left anterior frontotemporal derivations, without paroxysmal graphoelements.

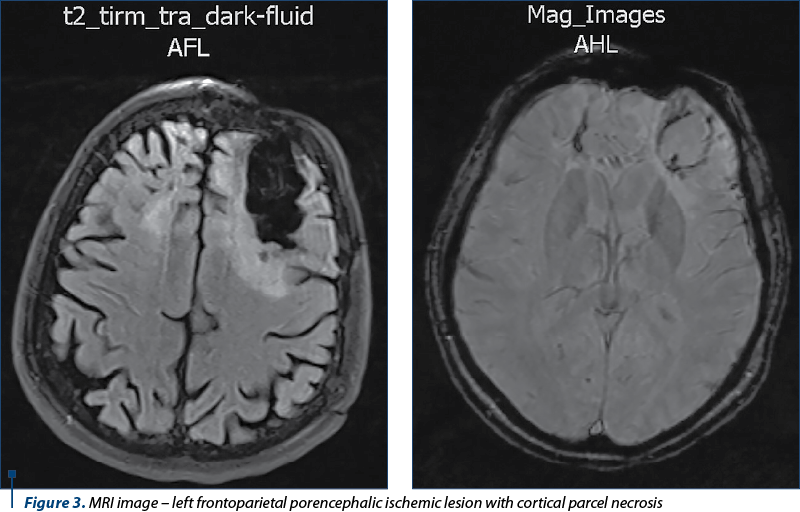

Cervical-cerebral MRI (Figure 3) reveals left intracerebral frontoparietal zone with hypersignal T2/FLAIR of 45/70 mm, with parceling lack of context, peripheral sequelae microhemorrhages. Edge with the same left frontal aspect of approximately 40/10 mm. No injuries to the brainstem. No visible MRI lesions in the C1-C4 cervical spinal cord. Ventricular system of normal volume, symmetrical on the midline. Eyeballs, retrobulbar spaces, craniofacial sinuses, pontocerebellar angles with normal MRI appearance. Mild bilateral mastoiditis. Pituitary gland with normal dimensions, without tumor formations. No intracerebral tumors. No suspicious multiple sclerosis injuries.

Toxicological tests – negative (breathalyzer alcohol test = 0).

Psychological examination: cognitive functions with slightly decreased efficiency, MMSE = 25 points, oriented temporally and spatially, slow comprehension, difficulties in fixing new information, hypoprosexia. Indices of emotional lability, poor impulse control, irritability with tendencies to explosive manifestations, low tolerance to frustration.

Neurological examination: sequelae after operated left frontal trauma, posttraumatic encephalopathy, posttraumatic epilepsy with grand mal seizures.

Social investigation: abandoned by his wife and the two children (he did not take his treatment, he consumed alcohol and used to beat her), in a two-room house without windows and door, in improper living conditions, with inadequate hygiene, the patient cannot take care of himself. His mother refuses to take care of him, because his wife has taken all his property. The father motivates that he is not the biological one and refuses to take care of him.

Positive diagnosis

Based on the reasons for hospitalization, anamnesis, psychiatric examination and related data, we support the multiaxial diagnosis.

AXIS I: Hallucinatory-delusional organic psychotic disorder.

-

Ethanolic dependence syndrome.

AXIS II: Organic epileptoid personality disorder.

AXIS III: Posttraumatic epilepsy with grand mal seizures.

-

Sequelae after frontal cranial trauma (2016).

-

Posttraumatic encephalopathy.

AXIS IV:

-

poor family support, separated from wife and children

-

inadequate social support (he lives alone, he has no friends)

-

financial issues

-

craniocerebral trauma due to work accident.

AXIS V:

-

GAF scale = 60 points

-

impairment in the family and professional field

-

the existence of a danger of injury to oneself or others.

According to DSM V criteria, hallucinatory-delusional psychotic disorder is established on the basis of the presence of auditory and visual hallucinations, delusional ideation of grandeur and mysticism and prosexia disorders, with distracting attention. It is organic, because the symptoms started after the cranicerebral trauma and in close connection with it.

The diagnosis of ethanol addiction syndrome is based on the fact that the patient consumes large amounts of alcohol which leads to inability to fulfill his obligations at home, disrupts family relationships and precipitates seizures, significantly decreasing the treatment compliance.

The diagnosis of personality disorder is established based on the behavior and the pattern of inner feelings that deviate markedly from the cultural norms of the society in which the patient lives, with disorders in the sphere of affectivity and interpersonal functioning and poor impulse control. It is also an organic personality disorder, because the patient’s personality has undergone significant changes compared to the one before the craniocerebral trauma, according to the information provided by him. It is an epileptoid personality disorder due to the viscosity of thinking, religiosity and excessive concern in the sphere of sexuality(6).

Differential diagnosis

Paranoid personality disorder: the patient does not show widespread distrust of others and does not consider himself exploited, unrighteous or deceived.

Schizoid personality disorder: the patient wants to reunite the family, has friends and enjoys the company of others and has an exacerbated interest in sexuality.

Schizotypal personality disorder: the patient does not have reference ideas, or bizarre beliefs, bodily illusions and, although he has a disorganized behavior, he is not bizarre.

Antisocial personality disorder: although the patient is impulsive and aggressive, he is also remorseful and conforms to some extent to the limits of the law.

Borderline personality disorder: the patient has been married since the age of 19, a relationship that worked until the time of the accident, which he wants to restore.

Histrionic personality disorder: the patient does not want to be the center of attention, and the affective modulation is weak.

Narcissistic personality disorder: although the idea of grandeur is present, the patient does not envy others and does not benefit from interpersonal relationships.

Short psychotic disorder: psychotic symptoms are long-lasting and resistant to treatment and are explained by cranial trauma.

Schizophrenia disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder): the lack of negative symptoms, especially those in the sphere of affect, makes the diagnosis differential, also the symptomatology being better explained by cranial trauma.

Hypomaniacal episode: the patient’s thinking is viscous, he is not more talkative than usual, and the need for sleep persists.

Mild neurocognitive disorder secondary to cerebral trauma: hypomnesia of fixation and evocation of mild intensity, post-amnestic gap during epileptic status.

Korsakoff syndrome: the changes in this patient cover the whole sphere of personality, not just cognition.

Mental retardation: the deficits of intellectual and adaptive functioning in the conceptual, social and practical fields did not appear during the development period, but after the cranial trauma.

Evolution and prognosis

Due to the lack of compliance with treatment, the lack of support from his wife and family and the harmful consumption of ethanol, the prognosis of the disease is reserved, and the frequency and intensity of epileptic seizures are expected to increase. Also, the impossibility of carrying out the professional activity, most of the financial problems, and the lack of a home are negative factors of evolution and prognosis (discontinuation of anticonvulsant and antipsychotic treatment).

Therapeutic management

Short-term goals:

-

remission of psychotic symptoms

-

behavioral improvement

-

obtaining adherence and therapeutic compliance.

Long-term and medium-term objectives:

-

prevention of relapses and exacerbations

-

mobilizing and increasing the quality of life

-

control of possible drug side effects and complications of the disease

-

awareness of the importance of antiepileptic treatment.

The proposed objectives can be achieved by:

-

pharmacological means

-

non-pharmacological means.

Pharmacological treatment

For the safety of the patient and his entourage, the patient is hospitalized.

The treatment was chosen according to the particularities of the case:

-

poor adherence to treatment according to the patient’s history

-

predominance of psychotic symptoms and behavioral disorders

-

harmful consumption of ethanol.

Thus, an atypical antipsychotic was chosen because:

-

it provides neuroprotection, prevents synapse plasticity

-

has a proven efficacy on affective symptomatology

-

offers superior safety and tolerability to first-generation antipsychotics

-

ensures a good profile of side effects (low risk of extrapyramidal effects and lower risk of lowering the seizure threshold).

Risperidone solution, in a total amount of 3 ml/day, was preferred because, in addition to those listed before, it has the following properties:

-

multireceptor action – it is a 5HT2A/DA/α1 antagonist, it does not react on M1

-

it has high affinity for 5HT, D2, α1, α2 receptors and low for β adrenergic

-

good profile of extrapyramidal effects

-

it ensures efficiency and safety in short-term administration.

Carbamazepine (600 mg in 3 doses per day) and levetiracetam (1500 mg in 3 doses per day) were also given to prevent epileptic seizures, and Rivotril® (6 mg per day in 3 doses) was used for the sedative effect.

There are monitored during treatment:

-

symptomatic responsiveness

-

the potential side effects

-

Risperidone – change in carbohydrate and lipid profile, onset of possible extrapyramidal symptoms, hyperprolactinemia, weight gain.

-

Carbamazepine – dizziness, confusion, headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, benign leukopenia, rash.

-

Levetiracetam – dizziness, ataxia, asthenia, decreased erythrocyte counts and hemoglobin.

-

Rivotril® – fatigue, depression, dizziness, ataxia, hypomnesia, confusion, hyperexcitability, irritability.

-

For these, there are necessary the monthly clinical evaluation of the patient, the paraclinical evaluation at 3-6 months, performing the hemoleucogram, assessing the lipid profile, the carbohydrate, along with ECG monitoring(7,8).

Psychotherapy

The association between psychotherapy and drug therapy is more effective than each of these methods applied in isolation.

Objectives: reduction of functional impairment; emotional/family support; helping the patient to adapt to a chronic disorder; teaching the patient to recognize prodrome symptoms; increasing the ability to adapt to the psychosocial consequences caused by the disorder.

Cognitive therapy: applied to increase compliance with drug treatment.

Behavioral therapy: it is effective because it can set limits on impulsive or inappropriate behavior through positive and negative reinforcement techniques; it is based on the theory of learning through conditioning; patients are taught how to adopt relapse prevention strategies(9).

Psychosocial interventions

Recreational rehabilitation programs include rehabilitation with sports, music therapy, and art therapy – painting.

Training social skills allows the patients to solve their problems, to engage in interpersonal relationships, to be able to use the support of others and to have an activity.

Work capacity expertise: at the last hospitalization in the Clinical Hospital of Psychiatry, the patient did not benefit from any form of social protection, moreover having no identity documents. During the hospitalization, the social assistance department helped the patient to obtain a temporary identity card, a disability allowance and made arrangements for the patient to obtain a disability pension.

Discussion

Due to the neurological and psychiatric therapeutic abandonment (2-3 months after each discharge) and alcohol consumption, the frequency and intensity of epileptic seizures increased, the psychotic phenomenology being accentuated. The patient also presented three traumas (craniocerebral and thoracic), all related to seizures, due to therapeutic abandonment. In 2020, the patient arrived at the ER Sibiu in epileptic status, with polytrauma, which required hospitalization in the intensive care unit of the neurology service. Heteroanamnestic, the patient also presented an exacerbation of psychotic phenomenology and behavioral disorders, having numerous conflicts with family members, resulting in violence against his wife and children, who decided to leave him. During this period, he had two more admissions to psychiatry, the reasons for hospitalization being motivated by psychotic phenomenology and heteroaggressiveness. Although there are no legal problems in the background due to neurological or psychiatric impairment, the patient does not seem to realize the consequences of the therapeutic abandonment, which raises the question of awareness of the condition and discernment, and may consider the patient eligible for art. 109 from the Romanian Penal Code. Through counseling, psychotherapy and minimizing the adverse effects of neurological or psychiatric therapy, attempts are made to improve the therapeutic compliance. An attempt is made to administer a minimally effective dose, at which the neurological and psychiatric symptoms may determine the absence of psychotic phenomenology and the control of seizures(10,11).

Taking into account the patient’s functional deficit, the lack of sociofamilial support (being abandoned in the hospital – homeless) and the precarious financial situation (disability allowance), it is necessary to involve the social assistance service within the hospital and try, as far as possible, the socioprofessional reintegration. At the presentation in our service, the patient did not have a valid identity card, and he was not insured by a health insurance house. During the hospitalization, the patient was helped to have a temporary identity card issued (he does not have a stable home, a personal property). He has also obtained a disability allowance and is helped to submit the necessary documents to obtain a disability pension. Although his condition has improved, the patient does not have the necessary autonomy to deal with his daily needs, and the family (wife, mother, father) refuses to come to take over the patient. For this reason, the patient is currently in the “Gheorghe Preda” Clinical Hospital of Psychiatry, Sibiu. The social assistance department has been trying for about 6 months to find a way for the patient to receive some form of social protection. In such situations, there is a need for sheltered housing that exists in very small numbers in Romania, as a result, in the case presented, asylum being the only solution of the patient (an impossible solution, given the age and the pathology of the patient, because there is no institution that can take over this case)(12).

The complexity of the case, beyond the medical implications, also raises legal and medico-legal issues. Here we refer to the aspects related to the work accident that led to a lawsuit with the employer. Due to the mental state, the repeated hospitalizations, the patient was not interested and was not represented by a legal representative in the divorce process (partition). Thus, the patient lost the material benefits obtained as a result of the process related to the work accident from his employer. Also, due to the evolution of the disease, the patient does not seem to realize the consequences of repeated cessation of treatment and raises the issue of a possible forensic psychiatric examination on the patient’s discernment and a possible safety measure – mandatory treatment. (13)

Conflicts of interest: Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Appreciation: We thank our colleagues in the specialties of neurosurgery, neurology, oral and maxillofacial and medical rehabilitation for the medical information provided and the involvement in making this presentation.

Bibliografie

- Dewan CM, et al. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2018 Apr 1;1-18.

- Georges A, Das JM. Traumatic Brain Injury. s.l. : StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2021. PMID: 29083790.

- Edwards G 3rd, Zhao J, Dash PK, Soto C, Moreno-Gonzalez I. Traumatic Brain Injury Induces Tau Aggregation. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2020 Jan 1;37(1):80-92.

- Koponen S, Taiminen T, Portin R, Himanen L, Isoniemi H, Heinonen H, Hinkka S, Tenovuo O. Axis I and II Psychiatric Disorders After Traumatic brain injury: a 30-year follow-up study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002 Aug;159(8):1315-21.

- Stubbs JL, Thornton AE, Sevick JM, Silverberg ND, Barr AM, Honer WG, Panenka WJ. Traumatic brain injury in homeless and marginally housed individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020 Jan;5(1):e19-e32.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

- New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry (3rd ed). Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Essential Psychopharmacology Prescriber’s Guide (6th ed). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Urech A, Krieger T, Frischknecht E, Stalder-Lüthy F, Grosse Holtforth M, Müri RM, Znoj H, Hofer. An Integrative Neuro-Psychotherapy Treatment to Foster the Adjustment in Acquired Brain Injury Patients - A Randomized Controlled Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020 Jun 2;9(6):1684.

- Green B, Norman P, Reuber M. Attachment style, relationship quality, and psychological distress in patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures versus epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2017 Jan;66:120-126.

- Sarkis RA, Pietras AC, Cheung A, Baslet G, Dworetzky B. Neuropsychological and psychiatric outcomes in poorly controlled idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2013 Sep;28(3):370-3.

- Vezzoli R, Archiati L, Buizza C, Pasqualetti P, Rossi G, Pioli R. Attitude towards psychiatric patients: a pilot study in a northern Italian town. European Psychiatry. 2001 Dec;16(8):451-8.

- Donisi V, Tedeschi F, Wahlbeck K, Haaramo P, Amaddeo. Pre-discharge factors predicting readmissions of psychiatric patients: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Psychiatry. 2016 Dec 16;16(1):449.