“Old age psychiatry’”or “Psychogeriatrics” is a shared competency of psychiatrists and geriatrics in Romania. However, up to date, little is known about service use patterns of geriatric department. Therefore, the specific aims of the proposed study were: 1) to examine the service use patterns of geriatric departments, 2) to ascertain the principal admitting diagnoses associated with hospitalization; and 3) to compare the different subgroups identified. In order to do so, routinely collected data for administrative purposes have been obtained and all discharges (N= 48906) from inpatient geriatric departments in Romania for the year 2010 have been analysed. Percentages of both the total number of discharges as well as the number of unique cases having a main psychiatric diagnostic (F ICD categories) or a G30 ICD code (Alzheimer disease) have been calculated. Results indicate that 1814 unique cases have been discharged in 2010 with a main psychiatric diagnosis and 448 with a G30 ICD diagnosis. More than half of the discharged patients belonged to the F0 category (N=1095), followed by anxiety (N=453) and mood disorders (N=240). However, when taking into consideration both main and secondary diagnosis, a much larger number of cases were identified (N=7346). Demographic data (such as age, gender, and living environment) as well as clinical data (such as referral method, type of discharge) have been further used to compare the identified subgroups.

Utilizarea serviciului staţionar de geriatrie de către persoanele în vârstă cu un diagnostic psihiatric în România

Inpatient geriatric service use by elderly with a psychiatric diagnosis in Romania

First published: 18 aprilie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.40.1.2015.4397

Abstract

Rezumat

„Psihiatria vârstnicului“ sau „psihogeriatria“ este o competenţă comună a psihiatrilor şi geriatrilor din România. Cu toate acestea, până în prezent se ştiu puţine lucruri despre tipurile de servicii oferite de departamentul geriatric. Prin urmare, obiectivele specifice ale studiului au fost propuse ca fiind:

1) examinarea serviciilor oferite de departamentele de geriatrie,

2) stabilirea principiului de internare pe baza diagnosticelor asociate cu spitalizarea; şi 3) compararea diferitelor subgrupuri identificate. În scopul realizării acestor obiective, în anul 2010 au fost analizate date colectate în mod obişnuit pentru scopuri administrative care au fost obţinute la toate externările (N = 48906) de la departamentele spitaliceşti de geriatrie din România. Au fost calculate procentele oţinute atât din numărul total al externărilor, precum şi numărul de cazuri unice având un diagnostic psihiatric principal (categoriile FICD) sau un cod G30 ICD (boala Alzheimer). Rezultatele indică faptul că 1814 cazuri unice au fost externate în 2010, cu un diagnostic psihiatric principal şi 448 cu un diagnostic G30 ICD. Mai mult de jumătate dintre pacienţii externaţi au aparţinut categoriei F0 (N = 1095), urmată de anxietate (N = 453) şi tulburări de dispoziţie (N = 240). Cu toate acestea, atunci când se iau în considerare atât diagnosticul principal, cât şi cel secundar, un număr mult mai mare de cazuri au fost identificate (N = 7346). Date demografice (cum ar fi vârsta, sexul şi mediul de trai), precum şi date clinice (cum ar fi modalitatea de trimitere, tipul de externare) au fost utilizate în continuare pentru a compara subgrupurile identificate.

Background

The mental health of older adults, while a topic of increasing concern, remains poorly addressed by mental health care systems, gaps in service provision being frequently reported in international literature. In the context of an aging population the fact that approximately 20% of adults ages 55 and over are suffering from a mental disorder (AOA, 2001) is worrisome. Most commonly reported mental disorders of the elderly are anxiety disorders (e.g., generalize anxiety and panic disorders), severe cognitive impairment (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease), and mood disorders (e.g., depression and bipolar disorder) (AOA, 2001). Nevertheless, the majority of these do not receive the services they need (Bartels et al., 2004), less than 3% of older adults accessing a mental health professional for their mental health problems (Lebowitz et al., 1997). Mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression adversely affect physical health, untreated depression in an older person with heart disease negatively affecting the outcome of the disease (APA, 2005). Conversely, older adults with medical conditions (e.g. heart disease) have higher rates of depression.

Despite the obvious impact, significant gaps in the provision of services for older people with mental health problems still exist (Tucker et al., 2007) at the National Service Framework for Older People (NSFOP). Some of the reasons identified for the existence of these gaps include: the stigma surrounding mental illness and mental health treatment; denial of problems; access barriers; fragmented and inadequate funding for mental health services; lack of collaboration and coordination among primary care, mental health, and aging services providers; gaps in services; the lack of enough professional and paraprofessional staff trained in the provision of geriatric mental health services; and, until recently, the lack of organized efforts by older consumers of mental health services (APA, 2005). Although approximately 70% of the population seeks health care in primary care settings (Regier, 1993) and GPs are frequently the gatekeepers to specialist mental health services (Todman, Law, & MacDougall, 2011), depression is under detected in older people, only one in six older people with depression discussing his symptoms with the GP and less than half of these receiving adequate treatment (Craig R. et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the services that may be needed by the different groups of older adults who need mental health care (severely mentally ill older adults, acutely distressed older adults, elderly people with dementia, and older adults with substance abuse problems) can greatly vary (Knight & Kaskie, 1995). In Romania, where the diversity of services is rather low, little information exist with respect to how the diverse range of needs of different sub-group categories (severely mentally ill older adults, acutely distressed older adults, elderly people with dementia, and older adults with substance abuse problems) are responded to by the mental health services.

Aims

More specifically, in Romania specialized mental health services for the elderly (‘old age psychiatry’ or ’Psychogeriatrics’) can be provided both by psychiatrists and MDs specialized in gerontology and geriatrics but little is known about what mental health problems are addressed in specialized geriatric departments and by how many people. Therefore, the specific aims of the proposed study were: to examine the service use patterns of geriatric departments and to ascertain the principal admitting diagnoses associated with hospitalization;

Methods

Routinely collected data for administrative purposes have been obtained and all discharges (N= 48906) from inpatient psychiatric (year 2013) and geriatric (year 2010) departments in Romania have been analysed. For the inpatient psychiatric dataset the analysis could be conducted only for episodes of care, unique patients identifiers (UPIs) being unavailable in the dataset. However, for the geriatric sample percentages of both the total number of episodes of cares as well as the number of patients with a main psychiatric diagnostic (F ICD categories) or a G30 ICD code (Alzheimer disease) were possible to compute.

Results

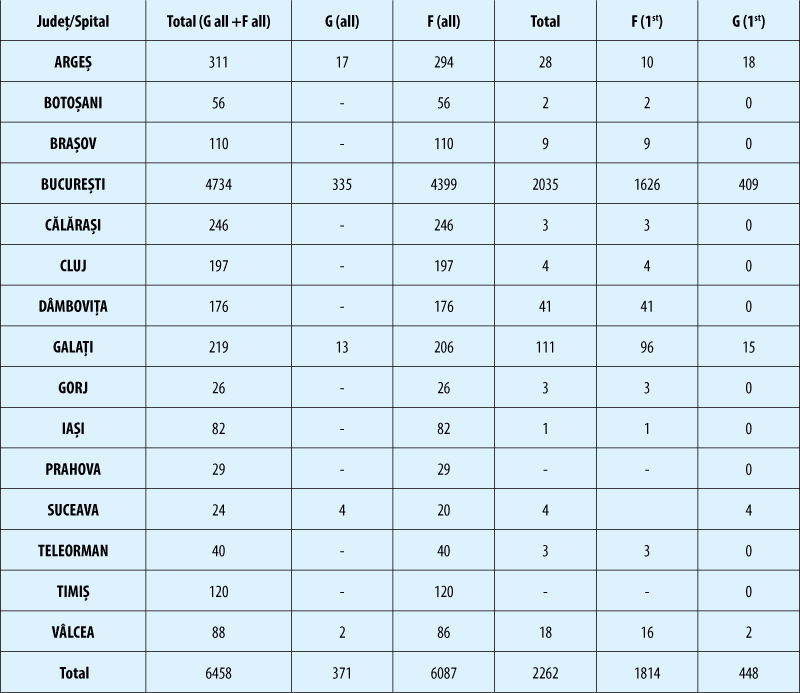

In Romania geriatric departments function in 18 hospitals located in 15 different counties, with a cumulative number of 980 beds, out of which 70% are located in Bucharest. Results indicate that out of 24453 unique cases discharged in 2010 from all inpatient geriatric wards in Romania 1814 patients had a main psychiatric diagnosis. The majority of these were female (72%), living in urban settings (76.5%) and had an average age of 71.8 years (SD=10.93 years). The average duration of stay was of 11.7 (SD=3) days and the main type of admission was by referral from the GP (86.7%). Around 10% of the discharges were emergencies and only about 3% referrals from the specialist. Diagnostic wise, the largest proportion was represented by patients with a F0 category diagnosis (60.3%) followed by F4 (24.9%) and F3 (13.2%). However, when taking into consideration both main and secondary diagnoses, 6458 of the unique cases have been identified. In the secondary diagnostic category, F4 diagnostics were the most frequent ones (41%) followed by F0 (35%) and F4 (41%). A breakdown by diagnostic subcategories revealed „mixed anxiety and depressive disorder“ to be the most frequent anxiety problem, both as a primary (90%) and secondary (57%) diagnosis. For mood disorders, most frequent diagnostic was F.32 (depressive episode) both as a primary and as secondary diagnosis.

A similar analysis of Results indicate that out of 24453 discharges in 2010 from all inpatient geriatric wards in Romania 1814 patients had a main psychiatric diagnosis. The majority of these were female (72%), living in urban settings (76.5%) and had an average age of 71.8 years (SD=10.93 years). The average duration of stay was of 11.7 (SD=3) days and the main type of admission was by referral from the GP (86.7%). Around 10% of the discharges were emergencies and only about 3% referrals from the specialist. Diagnostic wise, the largest proportion was represented by patients with a F0 category diagnosis (60.3%) followed by F4 (24.9%) and F3 (13.2%). However, when taking into consideration both main and secondary diagnoses, 6458 of the unique cases have been identified. In the secondary diagnostic category, F4 diagnostics were the most frequent ones (41%) followed by F0 (35%) and F4 (41%). A breakdown by diagnostic subcategories revealed „mixed anxiety and depressive disorder“ to be the most frequent anxiety problem, both as a primary (90%) and secondary (57%) diagnosis. For mood disorders, most frequent diagnostic was F.32 (depressive episode) both as a primary and as secondary diagnosis.

Conclusion

Specialized services for the elderly are scarce in Romania and unequally distributed, most of the existing bed capacity being concentrated in Bucharest. Roughly, one in four people admitted to these settings have a principal or secondary mental health diagnostic. These patients are more likely to be females, living in urban settings and suffering from a form of dementia, anxiety or a mood disorder, mixed anxiety and depression disorder and depressive episodes being the most frequently diagnosed in their respective categories (F3 and F4). Main types of access are represented by referral from the GP and emergency admissions. Taking into consideration the availability of specialized psychiatric services and planned character of the majority of these admissions, one possible explanation for the preference to be treated in geriatry rather than psychiatry is stigma avoidance. However, a systematic investigation of this preference at individual level is should be conducted in future studies.

Bibliografie

- Administration on Aging. (2001). Older Adults and Mental Health: Issues and Opportunities. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- American Psychological Association Office on Aging (2005). Psychology and Aging: Addressing Mental Health Needs of Older Adults. Retrieved from: http://www.apa.org/pi/aging/resources/guides/aging.pdf

- Craig R, Mindell J (eds) (2007). Health survey for England 2005: health of older people. London: The Information Centre

- Knight, B. G., & Kaskie, B. (1995). Models for mental health service delivery to older adults. In Emerging issues in mental health and aging (pp. 231–255). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

- Todman, J. P. F., Law, J., & MacDougall, A. (2011). Attitudes of GPs towards Older Adults Psychology Services in the Scottish Highlands. Rural and remote health, 11(1), 1496.

- Tucker, S., Baldwin, R., Hughes, J., Benbow, S., Barker, A., Burns, A., & Challis, D. (2007). Old age mental health services in England: implementing the National Service Framework for Older People. International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 22(3), 211–217. doi:10.1002/gps.1662