Membranous umbilical vessels at the placental insertion represents a velamentous umbilical cord without Wharton’s jelly, the rest of the umbilical cord being usually normal. The lack of Wharton’s jelly makes the vessels prone to compression and rupture, especially when they are located in the membranes covering the cervical os – in vasa praevia. Velamentous cord insertion is more common in twin pregnancies than in singletons. We report the evolution and management in a case of a twin dichorionic pregnancy with a single velamentous cord insertion. A 19-year-old woman, primigravida, para I, without prior investigations, presented at the ambulatory compartment of the “Elias” University Emergency Hospital Bucharest for a consult. An abdominal ultrasound was performed, showing a twin pregnancy with both alive, male fetuses, with significant difference between the estimated fetal weights. The patient refused the admission. After four days, she returned at the emergency ward with uterine contractions. The ultrasound revealed fetus A alive and fetus B without heartbeat. An emergency caesarean section was performed: a healthy neonate of 2690 g with APGAR 8, and a stillborn of 1241 g were delivered. Postpartum, it was determined that the pregnancy was dichorionic, diamniotic, with central umbilical cord insertion of the fetus A and a velamentous cord insertion of fetus B. The velamentous insertion on the interamniotic membrane for fetus B explained the fetal growth restriction and his antepartum death by rupture of a vessel.

Rezultat fatal într-un caz de inserţie velamentoasă de cordon la o sarcină gemelară bicorionică

Fatal outcome in dichorionic twin pregnancy with velamentous cord insertion – case report

First published: 17 decembrie 2019

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.67.4.2019.2769

Abstract

Rezumat

Inserţia velamentoasă presupune inserţia cordonului ombilical pe membrane, în afara plăcii coriale, la distanţă de marginea placentei. Lipsa gelatinei Wharton predispune la compresia şi ruptura vaselor ombilicale, în special când sunt localizate la nivelul membranelor ce acoperă orificiul cervical intern – vasa praevia. Inserţia velamentoasă de cordon este mai frecventă la sarcinile gemelare. Prezentăm evoluţia şi managementul unui caz de inserţie velamentoasă de cordon la o sarcină gemelară bicorionică, biamniotică, nedispensarizată. Pacienta, în vârstă de 19 ani, primigestă, primipară, s-a adresat Clinicii de obstetrică-ginecologie a Spitalului Universitar de Urgenţă „Elias” pentru investigarea clinico-paraclinică a unei sarcini nemonitorizate anterior. Examenul ecografic evidenţiază gestaţie gemelară, cu doi feţi de sex masculin, cu discrepanţă marcantă de creştere. Pacienta refuză internarea. După patru zile, pacienta se prezintă la camera de gardă pentru contracţii uterine dureroase. Examenul ecografic evidenţiază prezenţa unui făt viu (fătul A) şi a unui făt mort (fătul B). Se indică naşterea prin operaţie cezariană de urgenţă şi se extrage un făt A viu, de 2690 g, scor Apgar 8, iar fătul B, de 1690 g, nu prezintă semne de viabilitate. La inspecţia placentei, post-partum, se observă că sarcina era bicorială, biamniotică, cu inserţia cordonului ombilical al fătului A centrală, iar la fătul B inserţia era velamentoasă. Inserţia velamentoasă pe membrana interamniotică a fătului B a explicat creşterea insuficientă fetală, cât şi decesul antepartum al acestuia prin ruptura unui vas.

Introduction

Membranous umbilical vessels at the placental insertion represents a velamentous umbilical cord without Wharton’s jelly, the rest of the umbilical cord being usually normal. Two types have been described in literature: the first results in velamentous cord insertion with single placental lobe, and a second variety which is formed by vessels joining over the internal cervical os between lobes of a bilobed or succenturiate lobed placenta(1). The lack of Wharton’s jelly makes the vessels prone to compression and rupture, especially when they are located in the membranes covering the cervical os – in vasa praevia(2). Decreasing the blood flow to the fetus results in an increased risk for intrauterine growth retardation, abnormal fetal heart rate pattern and preterm delivery, but also a greater risk for umbilical cord thrombosis(3).

Vasa praevia complicates the outcome with severe hemorrhage, and many authors report a high perinatal mortality rate, between 52% and 66%(4). Reviewing an extensive Norwegian study, we found an increased incidence of hemorrhage and obstetrical maneuvers for the velamentous insertion of the umbilical cord in the third stage of labor(5).

A number of fetal abnormalities have been found to be associated with velamentous insertion, such as urethral obstruction, congenital hip dislocation, myelomeningocele, esophageal atresia, ventricular septal defects, cleft lip, fallot tetralogy, and trisomy 21(6).

Velamentous cord insertion is more common in twin pregnancies than in singletons, and in cases with twin placentas it has been proposed as a risk factor for developing selective intrauterine growth restriction(7).

We report the evolution and management in a case of twin dichorionic pregnancy with a single velamentous cord insertion.

Case report

A 19-year-old woman, primigravida, para I, without prior investigations, with first-trimester and second-trimester sonographic screening, presented at the ambulatory compartment of the “Elias” University Emergency Hospital Bucharest for a consult. An abdominal ultrasound was performed, showing a twin pregnancy with both alive, male fetuses, and in the breech presentation. With a last menstrual period (LMP) indicating a gestation of 37 weeks and 6 days, the biometry of the first fetus (fetus A) showed an estimated fetal weight (EFW) of 2470 g and gestational age (GA) of 34 weeks, while the second fetus (fetus B) had a EFW of 1240 g and a GA of 28 weeks.

The presence of a twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome was then suspected. Unfortunately, the patient refused admission at that time.

After four days, the patient returned at the emergency ward with uterine contractions. The ultrasound revealed fetus A with a fetal heart rate of 146 beats per minute, and fetus B without heartbeat. An emergency caesarean section was performed: a healthy neonate of 2690 g with an Apgar score of 8, and a stillborn neonate of 1241 g were delivered.

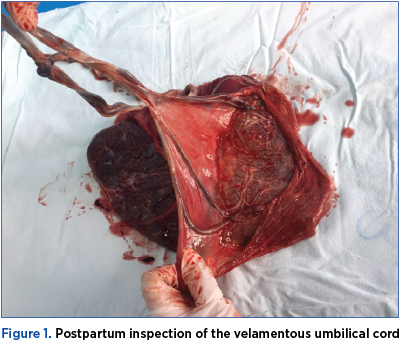

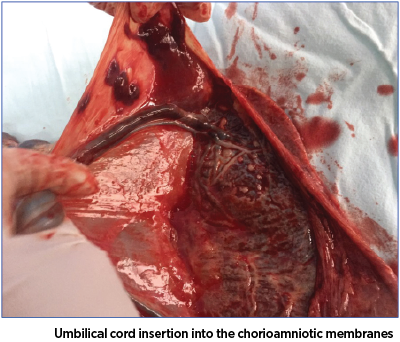

Postpartum, at close inspection of the placenta, it was determined that the pregnancy was dichorionic, diamniotic, with central umbilical cord insertion of the fetus A and a velamentous cord insertion of fetus B (Figure 1). The cause of death seemed to be a rupture of a vessel from the insertion of the umbilical cord of fetus B (Figure 2).

Discussion

The unfortunate turn of events in this case makes us think about what could be done to prevent this outcome in the context of this pathology.

Although recent methods of ultrasonography screening disproves traditional obstetrics that once claimed that death of a fetus with ruptured vasa praevia was almost unavoidable(4), perinatal mortality is still high in patients with no previous clinical care during pregnancy.

We must keep in mind the risk factors for vasa praevia and umbilical cord anomalies: placental pathology, twin pregnancies, in vitro fertilization(8) and fetal anomalies, but we must also know that screening should be done for all pregnancies because of the many cases with spontaneous conception and normal course of pregnancy until term.

A case we miss is a possible increase in perinatal mortality and has legal implications. Umbilical cord pathology should be prioritized by members of the screening community(9).

In the last decades, studies have established the importance of early diagnosis and the key role of ultrasonography in helping us achieve better results. Nowadays, the important question that is on every practitioner’s mind is: “When?”

A systematic review shows antenatal detection rates of vasa praevia between 53% and 100%, concluding that transvaginal ultrasonography is best for early diagnosis(10). The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Committee recommends early ultrasound evaluation of the placenta, umbilical cord and the relationship between them and the internal cervical os to be done whenever is technically possible, but no later than the second-trimester screening, for good results(11).

In terms of management for the cases early diagnosed, the purpose is to prolong pregnancy safety while trying to avoid complications.

In 2018, The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended that prophylactic hospitalization at 30-32 weeks of gestations should be individualized based on the risk factors in every case – multiple pregnancy, threatened premature labour and antenatal bleeding(12). Corticosteroids should be recommended from 32 weeks of gestation for fetal lung maturity due to the risk of preterm delivery(13).

Elective caesarean delivery should be considered before labor or membrane rupture takes place. In a large cohort study, the survival rate for fetuses diagnosed prenatally with vasa praevia was 97% for delivery at 34.9 ±2.5 weeks of gestation(14).

In cases of undiagnosed vasa praevia, because of the high rates of perinatal mortality earlier discussed, delivery should not be delayed whilst trying to confirm the diagnosis(12,15).

Conclusions

Our case is meant to be a cautionary tale for practitioners to further understand the implications of an undiagnosed umbilical cord abnormality, so they will advise women to be diligent, take clinical care seriously, and come to screening evaluations.

We presented the evolution of a case with prenatally undiagnosed velamentous cord insertion in a twin pregnancy with no other risk factor, no fetal anomalies, in a young woman without any pathologies associated. This was the particularity of the case.

Physicians should be vigilant and take into consideration all risk factors, but also know that not all cases with vasa praevia are diagnosed antenatally. n

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

2. Lockwood CJ, Russo-Stieglitz K. Velamentous umbilical cord insertion and vasa praevia. UpToDate. 2016.

3. Benirschke K, Kaufmann P. Pathology of the human placenta. 4th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag. 2000; pp. 229-32.

4. Lee W, Lee VL, Kirk JS, Sloan CT, Smith RS, Comstock CH. Vasa previa: prenatal diagnosis, natural evolution, and clinical outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 95(4):572-6.

5. Ebbing C, Kiserud T, Johnsen SL, Albrechtsen S, Rasmussen S. Third stage of labor risks in velamentous and marginal cord insertion: a population-based study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015; 94(8):878-83.

6. Bjøro K Jr. Vascular anomalies of the umbilical cord. II. Perinatal and pediatric implications. Early Hum Dev. 1983; 8(3-4):279-87.

7. De Paepe ME, Shapiro S, Young L, Luks FI. Placental characteristics of selective birth weight discordance in diamniotic-monochorionic twin gestations. Placenta. 2010; 31(5):380-6.

8. Oyelese Y, Spong C, Fernandez MA, McLaren RA. Second trimester low-lying placenta and in-vitro fertilization? Exclude vasa previa. J Matern Fetal Med. 2000; 9(6): 370-2.

9. Petca A, Petca RC, Zvâncă M, Maru N, Mastalier B, Dogaroiu C. Fetal death from ruptured vasa previa: a tragic event in the ultrasonographic era. Rev Med Leg. 2019; 27(1):43-6.

10. Ruiter L, Kok N, Limpens J, Derks JB, de Graaf IM, Mol BW, et al. Systematic review of accuracy of ultrasound in the diagnosis of vasa praevia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 45(5):516-22.

11. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Publications Committee; Sinkey RG, Odibo AO, Dashe J, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Consult Series #37. Diagnosis and Management of Vasa Praevia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015.

12. Jauniaux ER, Alfirevic Z, Bhide AG, Burton GJ, Collins SL, Silver R, on behalf of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Vasa praevia: diagnosis and management. Green-top Guideline No. 27b. BJOG. 2018; 126(1).

13. Society of Maternal-Fetal (SMFM) Publications Committee; Sinkey RG, et al. Diagnosis and management of vasa previa. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 213(5):615-9.

14. Oyelese Y, Catanzarite V, Prefumo F, Lashley S, Schachter M, Tovbin Y, et al. Vasa praevia: the impact of prenatal diagnosis on outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 103(5 Pt 1):937-42.

15. Irimescu T, Sevan-Libotean R, Staicu A, Albu C, Oancea AC, Goidescu IG, Mureşan D. Placental involvement in abnormal neonatal outcome. Obstetrica şi Ginecologia. 2018; 66(2):67-74.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Centre de screening regionale specializate: un proiect de reformă a screeningului în România

Cancerul mamar şi cel cervical continuă să reprezinte o problemă majoră de sănătate publică în România, cu diferenţe semnificative între România şi...

Valoarea predictivă a indicilor Doppler ai arterei uterine la 11-14 săptămâni pentru complicaţiile hipertensive ale sarcinii

Introducere. Complicaţiile hipertensive ale sarcinii pot duce adesea la situaţii grave, chiar cu potenţial letal pentru mamă şi făt. Ecografia Dopp...

O actualizare a ghidurilor internaţionale privind screeningul cancerului de sân

În ultimul deceniu, numărul cazurilor de cancer de sân a crescut cu 35% în întreaga lume. Screeningul prin mamografie determină scăderea certă a ri...

Screeningul cancerului de col uterin în România: este timpul pentru o schimbare

Cervical cancer is one of the most frequent female cancers in the world, mainly in the lower-resource countries. It is preventable through vaccinat...