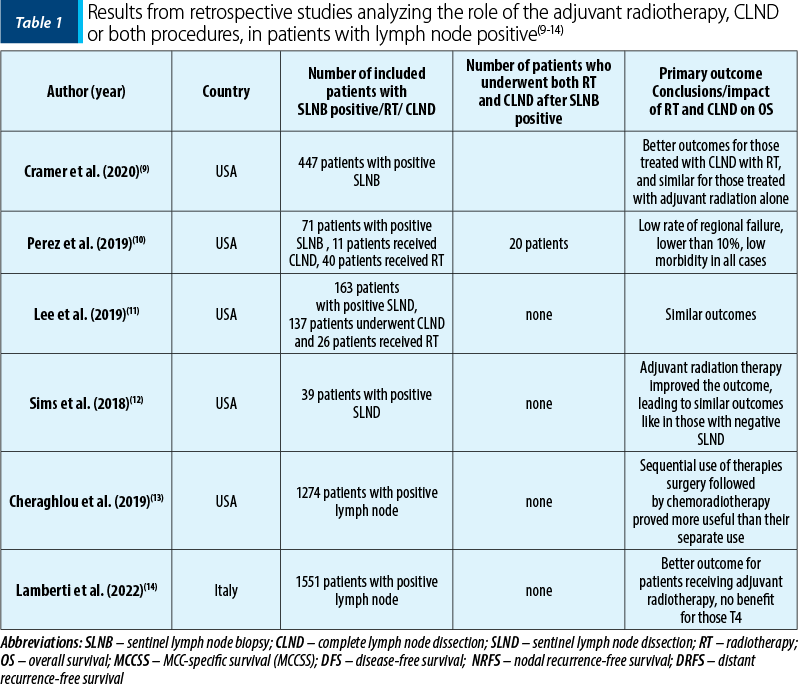

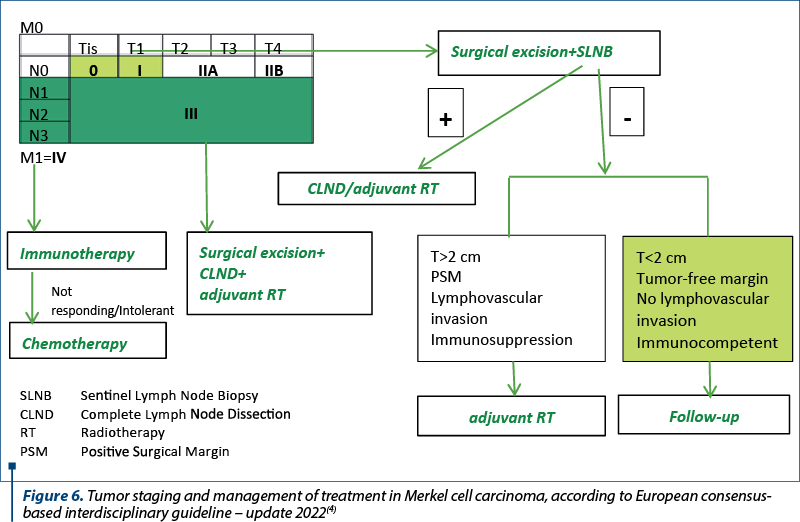

Introduction. Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is not as well-known as other malignant skin tumors, although it has been found to have a higher mortality rate than malignant melanoma, estimated at 30%. This poor prognosis is due to its aggressiveness characterized by an increased risk of recurrence, both regional and at distance. Materials and method. We conducted a literature review over the past five years, from January 2017 to September 2022, looking for relevant publications in the PubMed database, on Merkel cell carcinoma, or cutaneous neuroendocrine cancer, or trabecular skin cancer, as it is also known in literature, since 1972, when Toker first introduced the term. A total of 799 results were identified at the initial search in the database, which is why we added another secondary selection criterion by entering the terms “treatment” and “surgical excision”. In the end, 44 articles were analyzed, relevant for the surgical stage of the treatment and for its classification in multimodal treatment, excluding those that were not written in English. In addition, articles from the bibliographic indices were selected and consulted. Results. Six retrospective studies were selected, which analyze the role of adjuvant radiation therapy, complete lymph node dissection (CLND) or both procedures in patients with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy (SNLB). Conclusions. Surgery is the basic treatment, and the earlier it is applied by the first curative intention, the better the rest of the multimodal treatments manage to control the tumor evolution. Radiation therapy as a single therapy has not led to satisfactory results, even though Merkel cell carcinoma is highly radiosensitive, and will be considered only in addition to surgery.

Decision making in Merkel cell carcinoma – surgical oncologist point of view

Luarea deciziilor terapeutice în carcinomul cu celule Merkel – punctul de vedere al chirurgului oncolog

First published: 23 martie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/OnHe.62.1.2023.7745

Abstract

Rezumat

Introducere. Carcinomul cu celule Merkel (MCC) nu este atât de bine cunoscut precum alte tumori maligne ale pielii, deşi s-a constatat ca are o rată mai crescută a mortalităţii decât melanomul malign, estimată la 30%. Acest prognostic slab se datorează agresivităţii sale, fiind caracterizat printr-un risc crescut de recurenţă, atât regională, cât şi la distanţă. Materiale şi metodă. Am efectuat o analiză a literaturii de specialitate în ultimii cinci ani, din ianuarie 2017 până în septembrie 2022, căutând publicaţii relevante în baza de date PubMed cu privire la carcinomul cu celule Merkel, sau cancerul neuroendocrin cutanat, sau cancerul trabecular al pielii, aşa cum mai este cunoscut în literatură, încă din 1972, când Toker a introdus pentru prima dată termenul. Un număr de 799 de rezultate au fost identificate la căutarea iniţială în baza de date, fapt pentru care am adăugat un alt criteriu secundar de selecţie, introducând termenii „tratament” şi „excizie chirurgicală”. În cele din urmă, au fost analizate 44 de articole, relevante pentru etapa chirurgicală a tratamentului şi pentru încadrarea acesteia în tratamentul multimodal, excluzându-le pe cele care nu sunt scrise în limba engleză. Suplimentar, au fost selectate şi consultate articole din indicii bibliografici. Rezultate. Au fost selectate şase studii retrospective, care analizează rolul radioterapiei adjuvante, al limfodisecţiei complete (CLND) sau al ambelor proceduri la pacienţii cu tehnica ganglionului-santinelă pozitivă (SNLB). Concluzii. Chirurgia este tratamentul de bază şi, cu cât este aplicată mai devreme, de primă intenţie curativă, cu atât mai bine restul tratamentelor multimodale reuşesc să controleze evoluţia tumorală. Radioterapia ca terapie unică nu a condus la rezultate satisfăcătoare, chiar dacă MCC este înalt radiosensibil, şi va fi luată în considerare numai în completarea intervenţiei chirurgicale.

Introduction

In comparison with other skin malignancies, Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a lesser-known form of cancer than melanoma, although it has a higher mortality rate, with one in three diagnosed patients dying. Everyone has heard nowadays of malignant melanoma, but it is only the result of 300 years since the first report, and of sustained efforts to publicize the disease. The survival at 10 years comparing the two types of cancer was previously mentioned by the published studies to be lower in MCC compared to malignant melanoma, 17.7% versus 61.3%, according to the California Cancer Registry(1).

Regarding a recent skin cancers research publication in JAMA Dermatology, there were found higher rates of recurrence for patients treated for Merkel cell carcinoma than for those treated for melanoma and other cutaneous cancers, an approximately 40% recurrence rate(2,8) at five years. In this cohort study, including more than 600 patients, almost all recurrences were detected in the first three years, making them to conclude about the importance of careful supervision during this period.

The treatment of Merkel’s carcinoma has been completely revolutionized over the past five years by the introduction of targeted molecular therapies that have successfully replaced chemotherapy. The only constant with curative visa remains surgery, and scientific studies considered the wide excision to be the gold standard(3).

Not rarely, due to its clinical harmless appearance, the neuroendocrine cutaneous cancer predisposes to local excisions that are not given importance, both by patients and doctors, unfamiliar with such a rare disease(4,5). Therefore, the diagnosis is made late, in the presence of metastases, and we are losing the start in the fight against a relentless disease.

It is the merit of the acronym AEIOU(6) that has reached its goal of raising awareness among the population and, at the same time, equally important, among the specialists in the field. As a consequence of it, by increasing the diagnosis, the incidence has also increased.

As we well know, oncological patients rarely fit the rigid criteria of oncological protocols, whose role is only to guide the treatment plan. The responsibility of adapting it to the patient belongs to the multidisciplinary team. The surgeon leads the tumor board, being the one who diagnoses the cancer, with great expertise in clinical surgical scenarios. Furthermore, he is the trigger of this complex process of cancer treatment, because once the biopsy is done, the patient will later be directed to treatment. To know when a biopsy must be taken, from where and how to do this, is not always as obvious as it might seem, especially when the cancer clinically appears to be benign, as in the case of Merkel cell carcinoma.

In this paper, we propose to recall the role of the surgeon in the treatment of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin, as it has been reported a widely increase in incidence among non-Hispanic whites, particularly men, up to 50 years old. We also propose to discuss the key points of diagnosis and the difficulties encountered in the surgical treatment.

Materials and method

Because we have recently faced an increase in the number of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma referred to our clinic, we proposed to deepen our knowledge in the field and draw conclusions regarding the surgical approach of MCC, especially the per primam one.

We conducted a literature review for the last five years, from January 2017 to September 2022, searching for PubMed relevant publications regarding Merkel cell carcinoma, or neuroendocrine cutaneous cancer, or trabecular cancer of the skin, as it is otherwise known in literature, since 1972, when Toker(7) introduced the term for the first time.

A total of 799 results were identified from the initial PubMed search in this field, so we added another secondary selection criterion by using the terms “treatment” and “surgical excision”. Finally, only 44 articles were included, without classifying them according to a specific criterion, but excluding those not written in English. We also consulted additional appropriate articles selected from the references.

Results

Since all patients with Merkel cell carcinoma who came to our clinic for treatment also needed radical lymphadenectomy, several latest studies in the literature analyzing this specific problem caught our attention.

An important percentage of patients present themselves in an advanced stage, with nodal or metastatic dissemination from the moment of diagnosis, according to the statistics reported by several studies, this percentage reaching 40%(2,4). And among those who are in an early clinical stage at the onset, through the sentinel lymph node (SLN) technique, a statistically significant group of patients with nodal micrometastases are identified and recruited.

In the first study, Cramer et al.(9) analyzed 447 positive sentinel lymph node patients who underwent four different therapeutic approaches after excision of the positive SLN: 71 patients went for surveillance, 64 underwent complete lymph node dissection (CLND), 216 received adjuvant radiotherapy, and in 96 of the patients both complete lymph node dissection and subsequent adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) were performed. The results showed that complete lymphadenectomy alone without the addition of radiotherapy did not improve overall survival, but had better outcomes than the choice of surveillance after positive sentinel node identification.

The second study, of Perez et al.(10), evaluated 71 patients with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), where 11 patients (15.5%) underwent CLND, 40 (56.3%) received radiation, and 20 patients (28.2%) underwent CLND plus postoperative radiation. The outcomes were favorable in all types of treatment, with low morbidity and also with a low regional failure. Other risk factors may be taken into consideration for a more refined differentiation. In the third article, Lee et al.(11) also compared 163 positive SLN patients who underwent CLND (n=137) or RT (n=26). Median follow-up was 1.9 years. In patients in whom complete lymph node dissection was performed, after the identification and excision of the sentinel lymph node, an increase in survival at 5 years was observed, this being 71% compared to 64% in those who received only adjuvant radiotherapy after the identification of the sentinel lymph node, but without statistical significance (p=1.0). Also similar results for DFS (52% versus 61%; p=0.8), NRFS (76% versus 91%; p=0.3), or DRFS (65% versus 75%; p=0.3) were mentioned.

The fourth study, of Sims et al.(12), revealed that adjuvant radiotherapy succeeded in canceling the risk given by positive SLNB, giving patients equal chances of survival compared with those SLNB negative. The research conducted by Cheraghlou et al.(13) revealed better outcomes when surgery and adjuvant chemoradiation therapy were associated, with improved survival than with surgery or adjuvant radiation therapy alone. For lymph node-positive MCC, a new prognostic factor was measured, called Lymph Node Ratio (LNR)(13), in order to give a potential prognostic. This demonstrated to be an usefully treatment planning and follow-up after surgery. The last study, of Lamberti et al.(14), observed that adjuvant radiotherapy seems to have no benefit in T4 patients and in those with positive lymph node (Table 1)(9-14).

Regarding the aggressiveness of Merkel cell carcinoma, which relies on its ability to metastasize early in almost any organ, the liver and the lungs are the preferred sites for metastasis in solid organs, as many authors observed(4).

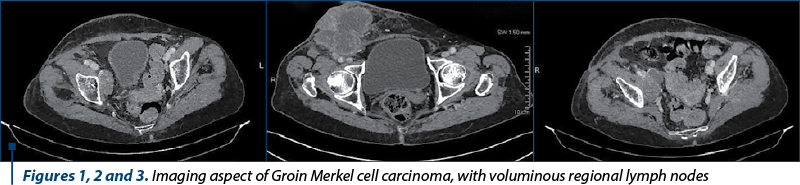

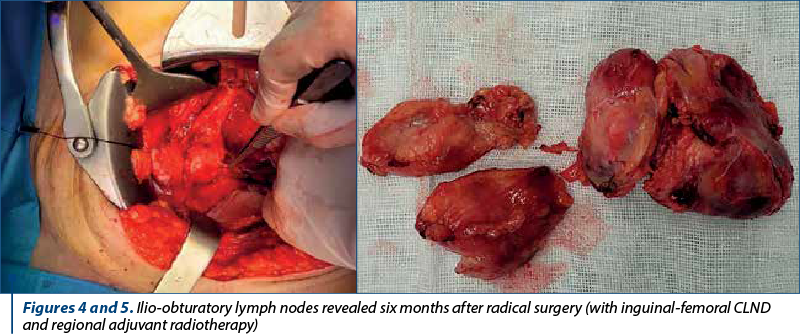

Overall, it was observed that MCC has a poorer prognosis due to the fact that patients initially present at a more advanced stage, with metastases, in a higher percentage than those with malignant melanoma(8). In terms of body distribution, in statistic reports it appears more frequently on the head and neck, and on extremities, while malignant melanoma has a predilection for the trunk(1). Only a few data in literature are discussing rare locations of Merkel cell carcinoma. In supporting the data from literature, we aim to address several aspects of one of the our most challenging cases of Merkel cell carcinoma, both regarding treatment and diagnosis, with aggressive behavior but with good response in maximal multimodal therapy (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 illustrate tomography and intraoperative images from an unusual case of groin Merkel cell carcinoma).

Postoperatively, the pathologic result was pT4N1, with intravascular lymphatic invasion present, Ki-67 positive 98%.

From the point of view of the surgical approach, we have two therapeutic options: Mohs micrographic surgery(15,16) and radical surgery of the wide local excision(22) type, both in circumference and in depth, excising the fascia.

In both cases, the results are good, and safety margins not invaded by tumor are obtained. The decision to perform one in favor of the other must be carefully planned according to the anatomical site distribution, and could require multidisciplinary approach, both general and plastic surgery(16,17).

Mohs micrographic surgery(15) is preferable in the case of tumor locations on the head where the cosmetic factor is extremely important and saves the skin, with the inconvenience that the sentinel ganglion technique must be performed first by a surgeon with oncological surgery skills, which complicates the patient’s path.

The sentinel ganglion technique must be performed before the wide excision of the tumor, when the lymphatic drainage channels have not been sectioned yet(12). Most of the time, it is followed by adjuvant radiotherapy on the regional lymph nodes. By that, sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) leads to the diagnosis of some cases in the early stages and increases the overall survival (OS).

Nodal metastases are the most common, depending on the location, raising difficulties in the surgical approach, but once addressed and excised, improve the patient’s prognosis(18,19).

Even in the case of small tumors where Mohs surgery solves the excision of the primary tumor, a systematic evaluation of all ganglion groups must be done, starting with the neighboring ones, of course, and with the clinical examination through a careful palpation(20).

Later, ultrasonography completes the evaluation. More importantly, in the absence of palpable or imaging-detected regional lymphadenopathy, the sentinel lymph node technique will be used, the studies performed demonstrating the effectiveness of the technique in detecting lymph node occult micrometastases(21). Both radiotherapy and radical lymph node dissection have proven useful in increasing survival and local and distant nodal recurrences, after SLNB was performed(22). Depending on the skin tumor location, lymph node dissection involves the risks of vascular, nerve or ureters damage(23). In such circumstances, there is required an increase expertise, and patients must be referred to a specialized center or to an experienced dedicated surgeon.

Severe preexisting conditions of the patient may pose challenges for both postoperative evolution and oncological outcome(23,24).

There were surgeons who also considered the laparoscopic or the robotic approach regarding inguinal and ilio-obturatory lymphadenectomy. This was taken into account for a faster postoperative recovery and for smaller incisions in an area with a high risk of contamination.

The largest first single institutional experience in treating MCC is from Memorial Sloan Kettering in which the specialists treated 250 patients over 30 years. They performed radical lymphadenectomy or sentinel lymph nodes in patients who clinically had no evidence of lymph node invasion, and found a high percentage of positive nodes in 16 out of 70 patients, which represented 23%, thus demonstrating the ease with which MCC can be substaged(25).

Discussion

Regarding pathogenesis, two major pathways are known in the oncogenesis of Merkel cell carcinoma: one is exposure to ultraviolet radiation, the other one, which represents 80%, involving the Merkel cell polyomavirus(26-28). Although the Merkel cell polyomavirus carcinoma seems to be part of the skin microbiota, the colonization occurs in children from the first months of life, especially after they are no longer protected by the mother’s antibodies(27). The promoter factor of tumor genesis is not yet known, and a vaccine for this has not yet been developed. Being a ubiquitous virus, cancer recurrence prophylaxis is rather aimed at improving immunocompetence and at avoiding exposure to ultraviolet rays, and also at educating the population to see a doctor when they notice suggestive skin changes(29).

Even in the case of small tumors where Mohs surgery solves the excision of the primary tumor, we must be prepared to do skin flaps because the location involves most of the time the areas with inextensible skin, such as the leg(30) or the front arm. Also, because of the tumor size and after a wide excision, surgical closure may need a skin graft, and this may later influence the adjuvant layering.

Thus, if there is agreement for adjuvant radiotherapy(30,31) treatment to be done within eight weeks after surgery, we have to consider that a skin flap may delay the radiation therapy.

The key to therapeutic success is an early diagnosis that allows radical surgery. The laparoscopic approach may represent an alternative and decreases the risk of dehiscence, related to persistent lymphorrhea, especially in the inguinal fold.

The high costs and the low incidence of cases do not allow for the refinement of the technique, nor the learning curve, perhaps only for surgeons who are already familiar with lymphadenectomy in urogenital, vulvar(30,32) or penian cancers. Particularly the comorbidities of elderly patients and biological parameters are some of the contraindications of general anesthesia. That’s what makes the technique rather suitable for early cases with micrometastases or for diagnostic, prophylactic purposes(33).

Otherwise, for advanced stages with voluminous lymph nodes adhering to the vessels, it becomes risky and the choice is not justified.

Merkel carcinoma surgery is a surgery of the lymphatic territory, therefore for the head and neck locations a modified laterocervical lymphadenectomy must be performed, a three-level axillary lymphadenectomy for upper arms located tumors and inguinal iliac and obturator lymphadenectomy for those located in the lower limbs(31,33).

The surgeon’s role in the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma is essential, from diagnosis to palliative care(33).

A high risk of relapse is reported, as well as metastasis, usually happening in the first two years after diagnosis(34-37).

Although immunotherapy has encouraging results, there are studies that observed a weak response to immunotherapy for specific locations of metastases, namely a resistance to those metastases disseminated at the cerebral and testicular level, because they become inaccessible to the host’s immune defense system or to systemic therapy. Some authors believe there are being protected in the so-called “sanctuary”(38) locations, by the blood-encephalic barrier and, respectively, the blood testicular network.

Lately, great strides have been made in the field of immunotherapy(39), and the use of anti-PD-(L)1 inhibitors registered a high therapeutic success in the metastatic stages of Merkel carcinoma, but a significant number of patients still develop resistance or do not effectively respond to therapy. Since it is known that 80% of Merkel cell cancer cases in the USA are positive for the Merkel cell polyomavirus, the use of vaccines in the fight against the disease, especially after the therapeutic success obtained in other cancers, such as cervical cancer, led to research in the field.

The small number of cases worldwide does not justify the costs of research and the production of a vaccine in this regard. Thus, a preventive vaccine for MCPyV is likely not cost-effective, but a therapeutic vaccine could be very useful for the population affected by the disease and especially in the prevention of recurrence which is quite high, between 25% and 75% in the USA(38).

Both CT and PET-CT are used as staging tools. It’s already been five years since chemotherapy is no longer the first line of treatment in metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma, being the backup solution for cases that do not respond to immunotherapy, or when the patients do not tolerate it and have adverse reactions. Other contraindications to immunotherapy are the personal history of solid organ transplantation and the autoimmune diseases.

Regarding the etiology of cancer, two forms are described: virus positive (VP-MCC) and virus-negative (VNMCC), with a more favorable prognosis for the first category in terms of response to treatment(37).

Initially introduced in the second line of treatment, avelumab increased the overall survival which doubled from six to approximately 12 months, being relatively well tolerated by patients, without major adverse reactions(39).

Also, a better response was observed in naive patients, who had not previously received chemotherapy, an effect explained by the immunosuppressive action of chemotherapy drugs. However, approximately half of the patients do not respond to immunotherapy, regardless of the presence of the polyomavirus(2). In single fractionated doses (SFRT), radiotherapy can be used as an immunostimulant. There are studies supporting the titers of T oncoprotein and MCPyV oncoprotein for monitoring patients after treatment, elevated levels of these biomarkers suggesting relapse and requiring an earlier clinical imaging evaluation(40,41).

Conclusions

Surgery is basic and the earlier it is applied for the first curative intention, the better the rest of the multimodal treatments manage to keep the disease under control. Radiotherapy alone did not give good results, even though Merkel cell carcinoma is highly radiosensitive, but must come in addition to surgery.

The resectability should be assessed by experienced surgeons, taking into account the risks versus the benefits, the patient’s desire and consent, always reminding the segment of affected patients – elderly or immunocompromised.

Salvage surgery with excision of single metastases followed by immunotherapy significantly prolongs survival in advanced stages for well selected patients.

Efforts should be directed towards primary diagnosis, this being the only one capable of ensuring the long-term survival.

New instruments of predicting the response to adjuvant therapy after positive SNLD are ongoing to be developed in further research. Until then, lymph node ratio (LNR) will prove its usefulness.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

-

Grabowski J, Saltzstein SL, Sadler GR, Tahir Z, Blair S. A comparison of Merkel cell carcinoma and melanoma: results from the California Cancer Registry. Clin Med Oncol. 2008; 2:327-33. doi: 10.4137/cmo.s423.

-

Harvey JA, Mirza SA, Erwin PJ, Chan AW, Murad MH, Brewer JD. Recurrence and mortality rates with different treatment approaches of Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2022 Jun;61(6):687-697. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15753.

-

Alves AS, Scampa M, Martineau J, Giordano S, Kalbermatten DF, Oranges CM. Merkel Cell Carcinoma of the External Ear: Population-Based Analysis and Survival Outcomes. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(22):5653. doi:10.3390/cancers14225653.

-

Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, Blom A, Bataille V, Dreno B, Del Marmol V, Forsea AM, Fargnoli MC, Grob JJ, Gomes F, Hauschild A, Hoeller C, Harwood C, Kelleners-Smeets N, Kaufmann R, Lallas A, Malvehy J, Moreno-Ramirez D, Peris K, Pellacani G, Saiag P, Stratigos AJ, Vieira R, Zalaudek I, van Akkooi ACJ, Lorigan P, Garbe C, Lebbé C; European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline – Update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug; 171:203-231. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.03.043.

-

Pasta V, Vergine M, D’Orazi V, Scipioni P, Monti M, Redler A. Merkel-cell carcinoma: preoperative clinical diagnosis and therapeutic implications. Ann Ital Chir. 2014 JulAug;85(4):352-7.

-

Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, Mostaghimi A, Wang LC, Peñas PF, Nghiem P. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(3):375-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.020.

-

Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105(1):107-110. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1972.01620040075020.

-

McEvoy AM, Lachance K, Hippe DS, et al. Recurrence and Mortality Risk of Merkel Cell Carcinoma by Cancer Stage and Time from Diagnosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(4):382–389. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.6096

-

Cramer JD, Suresh K, Sridharan S. Completion lymph node dissection for Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2020;220(4):982-986. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.02.018.

-

Perez MC, Oliver DE, Weitman ES, Boulware D, Messina JL, Torres-Roca J, Cruse CW, Gonzalez RJ, Sarnaik AA, Sondak VK, Wuthrick EJ, Harrison LB, Zager JS. Management of Sentinel Lymph Node Metastasis in Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Completion Lymphadenectomy, Radiation, or Both?. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(2):379-385. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6810-1.

-

Lee JS, Durham AB, Bichakjian CK, Harms PW, Hayman JA, McLean SA, Harms KL, Burns WR. Completion Lymph Node Dissection or Radiation Therapy for Sentinel Node Metastasis in Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(2):386-394. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-7072-7.

-

Sims JR, Grotz TE, Pockaj BA, Joseph RW, Foote RL, Otley CC, Weaver AL, Jakub JW, Price DL. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in Merkel cell carcinoma: The Mayo Clinic experience of 150 patients. Surg Oncol. 2018 Mar;27(1):11-17. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2017.10.005.

-

Cheraghlou S, Agogo GO, Girardi M. Evaluation of Lymph Node Ratio Association with Long-Term Patient Survival After Surgery for Node-Positive Merkel Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(7):803-811. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0267.

-

Lamberti G, Andrini E, Siepe G, Mosconi C, Ambrosini V, Ricci C, Marchese PV, Ricco G, Casadei R, Campana D. Lymph node ratio predicts efficacy of postoperative radiation therapy in nonmetastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: A population-based analysis. Cancer Med. 2022;11(22):4204-4213. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4773.

-

Ho C, Argáez C. Mohs Surgery for the Treatment of Skin Cancer: A Review of Guidelines. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; March 20, 2019.

-

Uitentuis SE, Bambach C, Elshot YS, Limpens J, van Akkooi ACJ, Bekkenk MW. Merkel Cell Carcinoma, the Impact of Clinical Excision Margins and Mohs Micrographic Surgery on Recurrence and Survival: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48(4):387-394. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003402.

-

Walecka I, Owczarek W, Ciechanowicz P, Dopytalska K, Furmanek M, Szczerba M, Walecki J. Skin manifestations of neuroendocrine neoplasms: review of the literature. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2022;39(4):656-661. doi: 10.5114/ada.2021.112073.

-

Lemos BD, Storer BE, Iyer JG, Phillips JL, Bichakjian CK, Fang LC, Johnson TM, Liegeois-Kwon NJ, Otley CC, Paulson KG, Ross MI, Yu SS, Zeitouni NC, Byrd DR, Sondak VK, Gershenwald JE, Sober AJ, Nghiem P. Pathologic nodal evaluation improves prognostic accuracy in Merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of 5823 cases as the basis of the first consensus staging system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(5):751-61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.056.

-

Shannon AB, Straker RJ 3rd, Carr MJ, Sun J, Landa K, Baecher K, Lynch K, Bartels HG, Panchaud R, Keele LJ, Lowe MC, Slingluff CL, Jameson MJ, Tsai KY, Faries MB, Beasley GM, Sondak VK, Karakousis GC, Zager JS, Miura JT. An Internally Validated Prognostic Risk-Score Model for Disease-Specific Survival in Clinical Stage I and II Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(11):7033-7044. doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-12201-z.

-

Naseri S, Steiniche T, Ladekarl M, Bønnelykke-Behrndtz ML, Hölmich LR, Langer SW, Venzo A, Tabaksblat E, Klausen S, Skaarup Larsen M, Junker N, Chakera AH. Management Recommendations for Merkel Cell Carcinoma – A Danish Perspective. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(3):554. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030554.

-

Sadeghi R, Adinehpoor Z, Maleki M, Fallahi B, Giovanella L, Treglia G. Prognostic significance of sentinel lymph node mapping in Merkel cell carcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic studies. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:489536. doi: 10.1155/2014/489536.

-

Yan L, Sun L, Guan Z, Wei S, Wang Y, Li P. Analysis of cutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma outcomes after different surgical interventions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(6):1422-1434. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.001. Epub 2018 Oct 5. [Erratum in: J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Oct;83(4):1237].

-

Ren K, Yin X, Zhou B. Effects of surgery on survival of patients aged 75 years or older with Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2022;11(1):128-138. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4437.

-

Milkovich J, Hanna T, Nessim C, Petrella TM, Weatherhead L, Chan AW, Irish JC, Murray C, Bannerman G, Holloway C, Forster K, Pazzano L, Wright FC, The Ontario Skin Cancer Advisory Committee. Restructuring Skin Cancer Care in Ontario: A Provincial Plan. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(2):1183-1196. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28020114.

-

Kukko H, Böhling T, Koljonen V, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma – a population-based epidemiological study in Finland with a clinical series of 181 cases. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(5):737-742. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.001.

-

Kouzmina M, Koljonen V, Leikola J, Böhling T, Lantto E. Frequency and locations of systemic metastases in Merkel cell carcinoma by imaging. Acta Radiol Open. 2017;6(3):2058460117700449. doi: 10.1177/2058460117700449.

-

Yang A, Wijaya WA, Yang L, He Y, Cen Y, Chen J. The impact of Merkel cell polyomavirus positivity on prognosis of Merkel cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1020805. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1020805.

-

Pietropaolo V, Prezioso C, Moens U. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(7):1774. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071774.

-

PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Merkel Cell Carcinoma Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); June 25, 2021.

-

Zhang Y, Sun Y, Mo J. Wide local excision for Merkel cell carcinoma of the lower extremity: A case report. Exp Ther Med. 2022;24(5):700. doi: 10.3892/etm.2022.11636.

-

Palencia R, Sandhu A, Webb S, Blaikie T, Bharmal M. Systematic literature review of current treatments for stage I-III Merkel cell carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2021;17(34):4813-4822. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-0574.

-

Petrelli F, Ghidini A, Torchio M, Prinzi N, Trevisan F, Dallera P, De Stefani A, Russo A, Vitali E, Bruschieri L, Costanzo A, Seghezzi S, Ghidini M, Varricchio A, Cabiddu M, Barni S, de Braud F, Pusceddu S. Adjuvant radiotherapy for Merkel cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2019;134:211-219. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.02.015.

-

Lebbe C, Becker JC, Grob JJ, Malvehy J, Del Marmol V, Pehamberger H, Peris K, Saiag P, Middleton MR, Bastholt L, Testori A, Stratigos A, Garbe C; European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel Cell Carcinoma. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(16):2396-403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.06.131.

-

Abu-Zaid A, Azzam A, Al-Wusaibie A, Bin Makhashen M, Jarman A, Amin T. Merkel cell carcinoma of left groin: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:431743. doi: 10.1155/2013/431743.

-

Patel P, Modi C, McLellan B, Ohri N. Radiotherapy for inoperable Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8(2):149-157. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0802a15.

-

Poulsen M, Round C, Keller J, Tripcony L, Veness M. Factors influencing relapse-free survival in Merkel cell carcinoma of the lower limb – a review of 60 cases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(2):393-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.014.

-

Foote M, Harvey J, Porceddu S, Dickie G, Hewitt S, Colquist S, Zarate D, Poulsen M. Effect of radiotherapy dose and volume on relapse in Merkel cell cancer of the skin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77(3):677-84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.05.067.

-

Tummala MK, Hausner PF, McGuire WP, Gipson T, Berkman A. Case 1. Testis: a sanctuary site in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24(6):1008–1009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7103.

-

Paulson KG, Bhatia S. Advances in Immunotherapy for Metastatic Merkel Cell Carcinoma: A Clinician’s Guide. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(6):782-790. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.7049.

-

Roberto M, Botticelli A, Caggiati A, et al. A Regional Survey on Merkel Cell Carcinoma: A Plea for Uniform Patient Journey Modeling and Diagnostic-Therapeutic Pathway. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(10):7229-7244. doi: 10.3390/curroncol29100570.

-

Nguyen AH, Tahseen AI, Vaudreuil AM, Caponetti GC, Huerter CJ. Clinical features and treatment of vulvar Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:2. doi: 10.1186/s40661-017-0037-x.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Review al carcinomului cu celule Merkel – ce se ştie şi ce nu se ştie?

Carcinomul cu celule Merkel (MCC) este o formă rară de cancer cutanat – carcinom neuroendocrin – şi se găseşte frecvent în regiunile corpului exp...