The impressions that the patient and his family leave on the doctor (physical, emotional and spiritual) are key elements in the coordination of palliative treatment in relation to the patient’s physical resources. Also, for detecting the physical, mental and spiritual impact that the disease has on the patient, the key element is the patient’s holistic approach. The authors of this article present the medical situation of a female patient with an unfavorable prognosis of the oncological disease, at the time of presentation in the palliation center, in which the holistic approach to the patient’s situation by the multidisciplinary team significantly improved the quality of the patient’s life and the perspective related to the end of life, and had an impact on the patient’s relationship with her family.

Oncological palliative therapy – clinical case presentation

Îngrijirea oncologică paliativă – prezentare de caz

First published: 31 mai 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/OnHe.63.2.2023.8088

Abstract

Rezumat

Impresiile pe care pacientul şi familia sa le lasă asupra medicului (fizice, emoţionale şi spirituale) sunt elemente-cheie în coordonarea tratamentului paliativ, în relaţie cu resursele fizice ale pacientului. De asemenea, pentru aprecierea impactului fizic, mental şi spiritual pe care îl are boala asupra pacientului, elementul central este reprezentat de abordarea holistică. Autorii acestui articol prezintă cazul unei paciente oncologice cu prognostic nefavorabil la momentul prezentării în centrul de îngrijiri paliative, în cazul căreia abordarea holistică a cazului de către echipa medicală multidisciplinară a îmbunătăţit considerabil calitatea vieţii pacientei şi perspectiva sa legată de sfârşitul vieţii, având, de asemenea, un impact pozitiv asupra relaţiei pacientei cu familia sa.

Introduction

Doctors able to approach the patient from a holistic point of view – i.e., to evaluate the biological parameters, as well as the psychological, social and spiritual ones in connection with the disease – manage to achieve better results for the treated patients(1-3). However, this holistic approach implies a deep therapeutic doctor-patient relationship. Likewise, social factors related to family support or spiritual factors related to the patients’ faith affiliation can have an impact on the therapeutic results, as well as on the patients’ quality of life(4-8).

Case presentation

In order to prioritize the importance of the holistic approach in oncology, we present the case of a 55-year-old female patient, married, with two children, from the urban environment, with secondary education, in the records of the territorial oncology service from January 2021, who upon presentation to the palliation center, in March 2022, was declared to have been exceeded from the point of view of oncological therapeutic resources, having an unfavorable prognosis due to the metastatic stage of the disease, the diagnosis being a fully operated gastric neoplasm, polychemotherapy, the disease in evolution through secondary hepatic, peritoneal and pulmonary metastases.

We decided to present the evolution of this patient who constantly had a fierce desire to live and fought for life, and the family support was substantial throughout the evolution of the disease. In the therapy of this patient, a permanent holistic approach to the problem was imposed by the multidisciplinary team, and the impressions left by the patient and her family on the medical team had a major contribution to the decision and therapeutic management.

At the time of taking into account the palliation center, the patient’s clinical condition was altered, complaining of pain in the upper abdominal floor, on the background of a marked asthenia and moderate dyspnea at rest, the imaging describing the presence of secondary hepatic and perirenal findings.

The family (husband and children) were aware of the diagnosis and the prognosis of the disease, which they accepted, but they expressly requested not to communicate to the patient that she suffered from a disease with an unfavorable prognosis.

The patient was a more emotionally unstable person with a tendency to develop depression and the family’s decision was understood and accepted by the medical team.

The family members were informed by the medical team about the role of palliative therapy, the only one they could benefit from, with a role in improving the quality of life and prolonging survival, but not in a significant way (in terms of months). Because the patient did not have contraindications for severe associated pathologies that would contraindicate hemodynamic support therapy or major antialgic therapy, and the ECOG status of the patient was medium to severe (IP=3), not being completely immobilized in bed and only requiring constant help in carrying out the daily activities, the medical team together with the family decided to administer symptomatic palliative therapy and hemodynamic support for vital functions.

We specify that in the oncology service, after the administration of the first therapeutic line at the imaging evaluation after six months, the continuation of the disease evolution at the hepatic and peritoneal level was detected, second-line cytostatic therapy being instituted, which the patient tolerated with difficulty, presenting hematological toxicity and severe grade II/III digestive adverse effects, which required continuous symptomatic, hematological and hemodynamic support therapy.

Despite the second-line cytostatic therapy, the neoplastic disease evolved; in the imaging evaluation at six months, the numerical and dimensional increase of the liver metastases was detected, as well as evolution at the pulmonary level.

As long as the patient continued the specific therapy in the oncology department, both the patient and the family had a state of peace and some hope, regarding a therapeutic response or the stabilization of the neoplastic disease.

From the moment when the disease no longer responded to the second-line cytostatic therapy, the patient became aware of the seriousness of her situation, especially due to the recurrent ascites, which required frequent evacuation points – recently, these were practiced even weekly. But from the moment when she was recommended symptomatic and supportive treatment (“best supportive care”), the patient’s physical and mental sufferings were inevitably felt by her and her family.

Initially, the patient did not accept in any form the idea that there are no alternatives to oncological therapy, being sure that there are other therapeutic possibilities to prolong her survival, but the physical, mental and spiritual degradation imposed the admission of the patient in a palliation center with the aim of providing adequate medical care, as well as psychological and spiritual support to both the patient and her family.

During the hospitalization in the palliation center, each administration of parenteral nutritional support (Aminoven®, Ringer) and hemodynamic support (physiological serum, glucose) increased the patient’s tonus and appetite, conferring a state of well-being and peace on the possibility of the evolution of the disease, which in the patient’s conception would mean the establishment of a state of fatigue marked by a decrease in appetite and even a definitive immobilization in bed.

On the other hand, the frequently performed paracentesis with the implicit improvement of discomfort and pain faded the state of panic that she was experiencing facing the continuation of the disease evolution.

The opioid treatment (morphine p.o.) instituted stopped the generalized pain, and corticotherapy (HHC i.v.) improved the dyspnea, eliminating the possibility of an unfavorable evolution of disease.

Thus, the patient became dependent on the palliative medical services, remaining in the palliative center until the end of her life, produced at an interval of more than six months from the moment of hospitalization, which was a major gain in survival, considering the evolution of the disease in an interval of less than six months under both first- and second-line oncology therapies.

During hospitalization, the major physical degradation for the patient was mainly due to recurrent ascites, which required repeated paracentesis, and marked physical asthenia, which immobilized her a long period in bed, creating a feeling of helplessness, hopelessness and especially uselessness, because she could no longer carry out her daily personal activities for which she was usually responsible.

Due to her helplessness and terrible physical fatigue, the patient refused to receive visitors, the only people she accepted around her being her family, the doctor and the priest.

However, the emotional pain of being separated from the loved ones and the fact that she would no longer be able to see them became more and more profound as the days passed and the disease worsened. Thinking that she would no longer live to see her niece grow up, as well as the separation from the two children (girl and boy) who saw her suffering, being powerless in the face of the disease, required the deep psychospiritual involvement of the multidisciplinary team from the palliation center.

The discovery by the psychologist of the patient’s experiences and the motivation of the patient to know her experiences and feelings, the spiritual side of things, by being close to God, made the patient to come to terms with the disease and its evolution.

The spiritual counseling provided permanently by the priest made her understand that there is a meaning for what happens and to accept the end as a closeness to God, creating a state of comfort and tranquility before the end of life. Also, the patient being able to accept the disease, also accepted that this was probably her fate. She reconciled with God and wanted a priest to go to confession. The disease deeply affected the relationships between the patient and the family at the end of her life, and the first to succumb physically and mentally were the family members, both the husband and the children, who still hoped that their mother would still recover and she will live. At the end of life, the patient, being reconciled with God and aware of her end, became more pleasant and much easier to bear for the family.

In addition, she began to give indications to the children regarding the future, when she would no longer be around, and the family continued to treat her with respect, capitalized on the ideas and indications that were given to them, which made the patient feel valuable further as a person in society. As such, it had become important for the family to ensure her comfort, the certainty that she was important for everyone and to offer her love, and this relationship and the patient’s soul reconciliation brought a state of peace, including for the family.

Towards the end of her life, the patient continued major III level antialgic therapy (oral morphine, as she could no longer swallow, was replaced with Fentanyl® patch), corticotherapy as needed, the patient having cardiac and respiratory decompensation, in the end permanent oxygen therapy was imposed, being recorded the patient’s death less than 12 hours after the onset of the comatose state.

The children were very happy that their mother was not in pain and that she had come to terms with God and the disease that she had accepted and that, until the end, she sat with them discussing and telling them what to do. The entire medical team as well as the family considered that she had a dignified end, being provided with physical comfort by suppressing the symptoms, as well as hygiene and bodily care, but especially peace of mind, by being close to the family, all these physical and psychospiritual aspects being essential for the human dignity and quality of life of a terminally ill patient.

Discussion

According to the World Health Organization (2002), palliative care is “that approach that improves the quality of life of patients and families facing the problems of a life-threatening illness, by preventing and alleviating suffering, through early identification, impeccable assessment and treatment of physical, psychosocial and spiritual problems”(6,7).

The National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services (1997) defined psychosocial care as the psychological and emotional support of the patient and his family(7,8). The word “holistic” comes from the Greek holos (ölloV), which means “whole”, “complete”, “all”, and holistic palliative care looks at the patient as a whole – body, mind, spirit, environment, relationships with family and social environment. As such, the individualized assessment of the patient in the palliation center requires the “impeccable” treatment of physical, psychosocial and spiritual problems(9).

The general or physical assessment of the patient in palliative care includes the assessment of the following parameters(12):

- The current stage of the disease and the risks or benefits of palliative therapy depending on the stage of the disease, ECOG performance status and associated comorbidities.

- The presence of signs and symptoms such as pain, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, constipation, insomnia, anxiety, depression, delirium or convulsions.

- The psychosocial state of the patients, based on the degree of understanding and acceptance of the disease by the patient and the family, the detection of the existence of an existential or spiritual crisis, of psychiatric or psychological symptoms, as well as the evaluation of social support (family, community) and material resources.

- The presence of an emergency such as hypercalcemia, superior vena cava syndrome, spinal cord compression syndrome, hemorrhage or intestinal occlusion.

A series of questions are asked in the holistic assessment of an oncology patient, related to the instruments used in patient’s assessment. If, from a physical point of view, pain can be evaluated quite precisely, the evaluation of the quality of life is difficult, requiring a complete evaluation of all aspects of everyday life, since each patient is unique and has unique experiences, needs, desires and goals(9-11). Only clinical judgment can help us select what is necessary and useful to evaluate and what tools to use in the evaluation, so that we get an overall picture of the patient and his family that is the basic unit in palliative care patients(12).

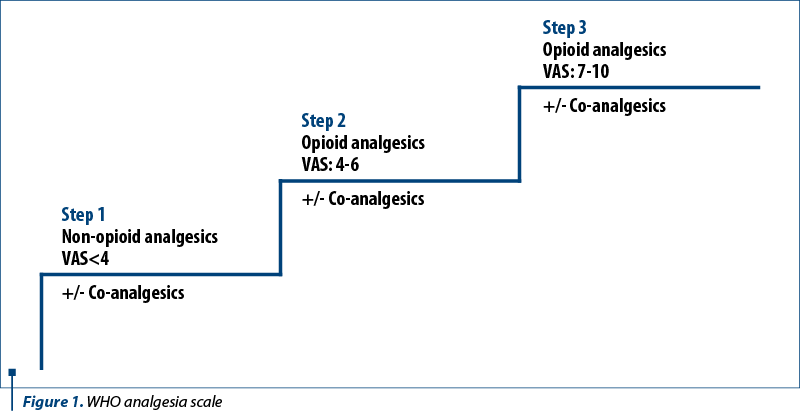

By evaluating the physical component of the oncological patient, the aim is to detect the intensity of the symptoms in order to abolish them therapeutically and improve the quality of life, the tools used being feasible and applicable according to the patient’s understanding(10-12): the Visual Analogue Scale, a numerical or verbal descriptive scale, to assess the intensity of the various symptoms. To measure the intensity of the pain, the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) is used: the patient places a cursor on a line that marks the absence of pain, at the left end, and the worst imaginable pain at the right end, depending on how intense the pain is felt, and on the back of the scale it is marked from 0 to 10, being able to quantify the intensity of the pain reported by the patient.

ESAS (Edmonton Symptomatic Assessment System) evaluates the intensity of the most frequently encountered symptoms: pain, nausea, anxiety, depression, drowsiness, dyspnea, fatigue, loss of appetite, comfort state. BPI (Brief Pain Inventory) provides details about pain: intensity, therapeutic evolution, how pain affects the general condition, the patient’s ability to move and work, relationships with peers, sleep and enjoyment of life. PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire) is a complex tool which provides details on both the presence and intensity of some symptoms (weakness, dyspnea, nausea vomiting, constipation, drowsiness, mobilization problems), as well as on some psychoemotional and social aspects (fears, worries, anxieties of the patient and his family, communication problems with the family or the care team).

PPS (Palliative Performance Score) evaluates five areas: mobilization, activity level evidence of the disease, self-care, nutrition and level of consciousness, correlating with the Karnofsky Performance Index.

To evaluate the psychoemotional component, the MMSE (Mini Mental State Examination) is a cognitive function evaluation tool which allows the measurement of orientation, immediate memory, short-term memory, attention and language.

To evaluate the family component, the genogram is used, which is a technique used in the psychosocial field, involving the graphic representation of the family structure, similar to a family tree.

To evaluate social belonging, the echo map is used as an evaluation tool, being a schematic representation of the individual’s relationships with the social environment, which, like the genogram, uses a series of specific symbols to represent the types of relationships. To evaluate the spiritual component, the FICA (Faith – Importance – Community – Address) scale is used, which evaluates the belonging to religion, cult, church and the way they are practiced and the significance of the value system and faith.

- F – Faith (Do you consider yourself a religious or spiritual person? Are you a believer?)

- I – Importance (Does faith give you support in dealing with the disease?)

- C – Community (Are you part of a spiritual/religious community?)

- A – Address (How can we help/support you in this regard?)

Within the pre-therapeutic assessment in palliative care centers, the individual application of these tools allows the detection of physical problems as well as psycho-spiritual and social ones, with a holistic therapeutic approach, as a whole, for the oncological patient, which allows improving the quality of life and support in managing the patient’s life and his family. Also, it is essential to detect the prognosis of the disease, in years (survival curves), months, weeks or days, a situation in which the relevant signs and symptoms are the establishment of oligoanuria or the impossibility of feeding, or the patient swallows with difficulty small amounts of liquids or has circulatory disorders (cold skin, pallor, cyanosis of the extremities) or an alteration of the state of consciousness or stertorous breathing(9-11). The major factors that influence the prognosis are: basic disease (location, metastatic stage of the disease), performance status (e.g., ECOG 3®survival <3 months; ECOG 4® survival <1 month), associated comorbidities (e.g., hypercalcemia® survival 30-135 days).

The term “palliation” comes from the Latin pallium, which means “to cover”, and in today’s language it means to relieve and control the symptoms of the disease by administering symptomatic and supportive treatments, as well as psychoemotional and spiritual support. Supportive therapy focuses on physical symptoms (pain, nausea, vomiting, weight loss), the abrogation of this therapy, leading to physical, mental and spiritual degradation with alteration of the quality of life and shortening of patients’ survival(13).

Pain in cancer is often multifactorial and complex, about 60% of the sensations of pain being due to the tumor, 20% representing the effects of the treatment, and 20% being the consequence of some individual factors(15). The tendency for doctors is to increase the dose of opioids or change the regime of treatment depending on the intensity of the pain, without taking into account the fact that the pain has a physical component, due to the neoplastic disease, but also a psychological component related to the psychoemotional state of the patient, which reflects the state of his relationship with his family and their support that brings benefits(14-16).

The appropriate analgesic will be chosen depending on the intensity of the pain and in the appropriate dose to attenuate the pain, the administration being mandatory to be done at regular time intervals and preferably orally, the levels of analgesia being dictated by the VAS intensity of the pain.

Fatigue or unusual tiredness can affect the quality of life more than the pain, exhausting the patient physically, emotionally and mentally, with the onset of depressive mood. Fatigue therapy includes medicinal measures, namely psychostimulants (dextroamphetamine, antidepressants, corticosteroids) and non-medicinal measures guided by energy conservation (establishing priorities by eliminating unessential activities, scheduling activities at peak energy hours, short sleep during the day) or psychosocial interventions (relaxation therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, distraction through play, music, reading or socializing), and a fatigue diary can help identify the precipitating factors and monitor the severity of complaints(12,16-19).

In the context of frequent and more severe dyspnea in the weeks preceding death, patients may experience panic attacks, manifested by a feeling of imminent death, anxiety with worsening dyspnea, creating a vicious circle with potentially lethal worsening of the general condition. First of all, it is important to reassure the patient, the answers to the patient’s questions being given using a calm and confident tone, and the non-medicinal measures consist of ensuring a quiet environment, without noises, and intermittent or permanent oxygen therapy as needed.

Dyspnea therapy involves the administration of bronchodilators, morphine that relieves the sensation of dyspnea, and benzodiazepines (Diazepam®) at bedtime(22).

The cachexia-anorexia syndrome is manifested by anorexia, marked weight loss, fatigue and lethargy, to which is added secondary anemia with skin pallor, the appearance of edemas due to hypoalbuminemia and increased generalized pain sensitivity, accusations doubled by the sociopsychological implications, namely the accentuation of the feeling of loss of body image, of fear and isolation from the family and the social environment. The treatment consists of: increasing food intake through hypercaloric diets or nutritional supplements administered enterally/parenterally, corticosteroid treatments to stimulate the appetite, but which do not solve the problem of cachexia due to increased tumor metabolism, as well as care measures for the integuments, mucous membranes and the oral cavity, but the impact of psychological counseling is very important in preventing the onset of depressive states due to the feeling of hopelessness in the face of suffering and disregard for the one’s own person(12,20,21).

Mental or cognitive disorders, such as the reduction of the efficiency of cognitive functioning, dementia and exogenous psychoses arising in the evolution of the neoplastic disease, require the intervention of the psychotherapist who will impose on the medical team a behavior of treating the patient with politeness and respect, trying to remove his fear and suspicion about the end of life and encouraging the presence of the family or a close friend with the patient. However, agitated patients, with hallucinations or in a paranoid state, will receive medication, namely haloperidol (p.o. or s.c.), or corticotherapy (dexamethasone), and cerebral depletives in case of brain tumors(23).

The totality of patients’ needs, such as the maintenance of independence, the ability to carry out activities and the management of pain and the side effects of treatments, are strongly correlated with the level of life quality, which is more precarious when these needs accused by patients are multiple and complex. Improving the quality of life can be achieved by changing the patient’s expectations and bringing them closer to reality, in this regard, the primary thing being the correct and accurate information of the patient concerning the effectiveness of the treatment, its toxicities and the possibilities of recovery.

The quality of life is not something stable, it presents changes depending on the evolution of the disease, the daily assessment of the 14 needs of the patient being necessary:

1. the need to breathe

2. the need to eliminate

3. the need to feed and hydrate

4. the need to sleep and rest

5. the need to be clean/cared for and take care of the skin and mucous membranes

6. the need to move and have a good posture

7. the need to communicate

8. the need to dress/undress – dependency score

9. needs related to the practice of religion, the rights of the patient, spiritual counseling

10. the need to keep the body temperature within normal limits

11. the need to avoid dangers

12. the need to be useful

13. the need to recreate

14. the need to learn to manage their health(22,23).

The terminal state refers to the last hours of the patient’s life, when interventions must be adapted to the needs and purpose of care. The palliative care team must approach the terminal condition on four levels: physical, psychoemotional, spiritual and social. In the last days before death, patients begin to present symptoms such as fatigue, pain, restlessness, agitation or delirium, noisy or labored breathing, the impossibility of administering oral medication, but only small amounts of liquids, and permanent immobilization in bed. As the general condition deteriorates, the symptoms become more and more complex, often creating tense situations in the family and, at the same time, they can negatively burden the palliative care team.

In the management of imminent death, the key elements are the recognition of the terminal condition and the correct application of the therapeutic protocol that provides for the preparation of the family for the acceptance of imminent death, the simplification of the therapeutic scheme with the transition from the administration of oral to subcutaneous medication to control serious symptoms (stertorous breathing, dyspnea, agitation, delirium, pain), applying comfort measures and maintaining the patient’s dignity (ensuring personal hygiene, oral care, communication with the patient), offering religious and spiritual support, psychoemotional counseling, and targeted support for anticipatory mourning(24-25).

Conclusions

The authors of this article aimed to present the medical situation of a patient with an unfavorable prognosis of the oncological disease, in which the holistic approach to the patient’s situation by the multidisciplinary team significantly improved the quality of the patient’s life and the perspective related to the end of life, and had an impact on the patient’s relationship with her family.

The doctor-patient relationship is essentially a medical relationship which requires knowledge about the physical and biological state of the patient, but in the palliative treatment of the oncological patient, it is essential to perceive the individual psychology of the patient and his family, which are decisive factors in the therapeutic management of the patient at the end of life.

However, the doctor’s empathy in communication is extremely important, because the doctor must understand what the patient is going through, so that he can encourage him to express himself openly and unfettered. In this context, we can say that this doctor-patient communication is a complex process that requires attention, time, effort, involvement and medical training.

In the holistic approach to the oncological patient, in addition to an approach to the physical problems of the patient, the psychological and spiritual experiences are also detected, as well as the relationships on the social scale and the material support available to the patient, aspects that can be solved correctly through an adequate psychological, social and spiritual counseling.

This holistic physical, mental, spiritual and social approach to the patient is only possible within a multidisciplinary team, where the doctor in the therapeutic decision has the support of the psychotherapist, the spiritual counselor and the social worker.

The holistic approach is possible to be carried out at a high-performance level only in palliative care centers. Through this work, the authors want to raise awareness on the importance of the holistic approach to the oncological patient, an approach that ensures an adequate quality of life and a prolongation of the patient’s survival, with dignity, an essential condition for human existence.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY

Bibliografie

- WHO. Essential Medicines in Palliative Care (January 2013).

- Watson M, Lucas C, Hoy A, Wells J. Oxford Handbook of Palliative Care, 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Sporiş M. Evaluarea pacientului. Viaţa medicală. 2014 Jun 6;23(1273).

- Spiegel D. Effects of psychotherapy on cancer survival. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2(5):383-389.

- Mager WM, Andrykowski MA. Communication in the cancer ‘bad news’ consultation: patient perceptions and psychological adjustment. Psychooncology. 2002;11(1):35-46. doi:10.1002/pon.563.

- Riley J. Standards and norms for palliative care în Europe. European Journal of Palliative Care. 2009;16(6). Palliative care: the solid facts. Report WHO 11/04, 22 July 2004.

- Jeffrey D. What do we mean by psychosocial care in palliative care? In: Lloyd-Williams M. Psychosocial Issues in Palliative Care. Oxford University Press, USA, 2003.

- Guyton AC. Texbook of Medical Physiology. 6th Edition, W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, 1981.

- Berger A, Portenoy KR, Weissman DE. Palliative Medicine. In: Principles and practice of supportive care. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, 1998.

- Doyle D, Hanks WCG, Mac Donald NM (Eds.). Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine, Second edition. Oxford Medical Publications, Oxford,1998;489-776.

- Moşoiu D. Protocoale clinice pentru îngrijiri paliative. Ediţia a II-a. Ed. Haco, Braşov, 2013.

- Ventafriedda V. Quality of life in oncology. In: Pollock RE (Ed.). Manual of clinical Oncology, 7th Edition, Wiley-Liss Inc, New York, 1999;791-803.

- Moşoiu D. Ghid practic. Prescrierea şi utilizarea opioidelor în managementul durerii. Lux Libris, Braşov, România, 2007.

- Wenghofer EF, Wilson L, Kahan M, et al. Survey of Ontario primary care physicians' experiences with opioid prescribing. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(3):324-332.

- Patrick DL, Ferketich SL, Frame PS, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Symptom Management in Cancer: Pain, Depression, and Fatigue, July 15-17, 2002. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(15):1110-1117. doi:10.1093/jnci/djg014.

- Stein KD, Martin SC, Hann DM, Jacobsen PB. A multidimensional measure of fatigue for use with cancer patients. Cancer Pract. 1998;6(3):143-152.

- Hann DM, Jacobsen PB, Azzarello LM, et al. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: development and validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(4):301-310. doi:10.1023/a:1024929829627.

- Hann DM, Denniston MM, Baker F. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: further validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(7):847-854. doi:10.1023/a:1008900413113.

- Stasi R, Abriani L, Beccaglia P, Terzoli E, Amadori S. Cancer-related fatigue: Evolving concepts in evaluation and treatment. Cancer. 2003;98(9):1786–801.

- Davis MP, Dreicer R, Walsh D, Lagman R, LeGrand SB. Appetite and cancer-associated anorexia: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(8):1510-1517. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.03.103.

- Twycross RG, Lack SA. Therapeutics in terminal cancer, Second Edition. Churchill Livingstone, 1990.

- Selman LE, Higginson IJ, Agupio G, et al. Quality of life among patients receiving palliative care in South Africa and Uganda: a multi-centred study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:21.

- Kass-Bartelmes BL, Hughes R. Advance care planning: preferences for care at the end of life. Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy. 2004;18(1):87-109.

- Murphy D, Ellershaw JE, Jack B, et al. The Liverpool Care Pathway for the rapid discharge home of the dying patient. Journal of Integrated Care Pathways. 2004;8(3):127-128.

- Ellershaw J, Ward C. Care of the dying patient: the last hours or days of life. BMJ. 2003;326(7379):30-34.