Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is rare in younger people, with the highest incidence between the ages of 40 and 60 years old and, due to its particular anatomical location and lack of early symptoms, it is often diagnosed in advanced stages. A thorough research of the literature reveals limited information regarding imunotherapy in cancers associated with chronic hepatitis. We report the case of a young man with metastatic nonkeratinizing nasopharyngeal carcinoma and viral C hepatitis, with sustained therapeutic response to standard chemotherapy and excellent outcomes with imunotherapy.

Răspuns terapeutic promiţător la imunoterapie într-un carcinom nazofaringian metastazat asociat cu hepatită virală C – caz clinic

Promising response to immunotherapy in metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma associated with hepatitis C virus – a case report

First published: 09 aprilie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ORL.51.2.2021.4945

Abstract

Rezumat

Carcinomul nazofaringian este rar la tineri, având incidenţa maximă între 40 şi 60 de ani şi, din cauza localizării sale anatomice particulare şi a paucităţii de simptome precoce, este adeseori diagnosticat în stadii avansate. Un studiu de literatură amănunţit a relevat puţine informaţii referitoare la imunoterapia în cancere asociate cu hepatită cronică. Prezentăm cazul unui bărbat tânăr, cu carcinom nazofaringian nekeratinizant metastazat şi hepatită virală, cu răspuns terapeutic susţinut la chimioterapia standard şi cu rezultate excelente la imunoterapie.

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is originating in the epithelial cells of the nasopharynx.

In 1921, the German pathologist Alexander Schminke along with the French radiologist Claude Regaud published the first paper on this hystology, described as a distinct entity from other types of throat cancers(1).

In 2020, the International Agency for Research on Cancer announced approximately 133,354 new cases of nasopharyngeal carcinoma, with higher incidence in males, and a ratio of about 2.6 in worldwide statistics. In the overall population, the peak incidence occurs between 50 and 60 years old.

There is an unbalanced global distribution, and South-Eastern Asia is an endemic region, with 85.2% of the total new cases(2).

The World Health Organization (WHO) classified in 2005 nasopharyngeal carcinoma into three main pathological subtypes: keratinising squamous cell carcinoma, nonkeratinising carcinoma, and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma(3).

The most important risk factors associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma include host genetics, environmental factors, and Epstein-Barr virus infection.

Epstein-Barr virus is almost always present in nasopharyngeal cancers, being correlated with a poor prognosis and highly associated with nonkeratinizing carcinoma.

Several epidemiological studies suggested a positive association between nasopharyngeal carcinoma and the consumption of preserved food and salted fish, poor oral health, and active or passive tobacco smoking. Moreover, people with a family history of nasopharyngeal carcinoma present a significantly higher risk of developing nasopharyngeal cancer(4-6).

This present report describes the treatment and evolution of a 25-year-old patient with metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Case report

A 25-year-old male, former smoker, with chronic hepatitis C virus infection and no oncological family history, was admitted to the “Elias” University Emergency Hospital, Bucharest, at the end of 2017.

His medical background presented a nasopharyngeal carcinoma diagnosed by endoscopic biopsy in July 2017. The histology report confirmed poorly differentiated nonkeratinizing squamous cell nasopharyngeal carcinoma, clinically staged T4N2M0, stage IV according to the fifth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer. The CT scan showed a left-sided mass in the nasopharynx, with skull base invasion and extension into the left carotid space, left ethmoid and sinus, and supracentimetric left and right laterocervical lymph node metastasis.

The patient received three courses of concurrent chemotherapy with cisplatin and external radiotherapy, with a total dose of 48.6 Gy, between September and October 2017. After definitive chemoradiotherapy, he underwent flexible fiberoptic pharyngoscopy which revealed no tumor mass, but diagnosed grade III radiation induced mucositis. A hole-body CT scan and bone scintigraphy showed no metastasis.

The definitive chemoradiotherapy was followed by adjuvant systemic therapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil, with a total of six cycles.

At the end of adjuvant chemotherapy, cerebral and cervical MRI showed nasopharyngeal asymmetry with focal thickening of the right-side wall with Rosenmüller fossa obstruction and enhanced contrast at this level. Chest CT scan was also conducted and did not reveal any metastasis. Given the nasopharyngeal location of the tumor and its frequent association with metastatic spread, it was agreed that PET-CT should be performed. This was done at the end of April 2018 and showed residual metabolic activity in the cavum, along with metabolically active bone lesions in the L2-L4 vertebrae.

Unfortunately, after the PET-CT, the patient neglected his disease until August, when it was decided to perform a biopsy of a bone lesion that confirmed the imaging suspicion.

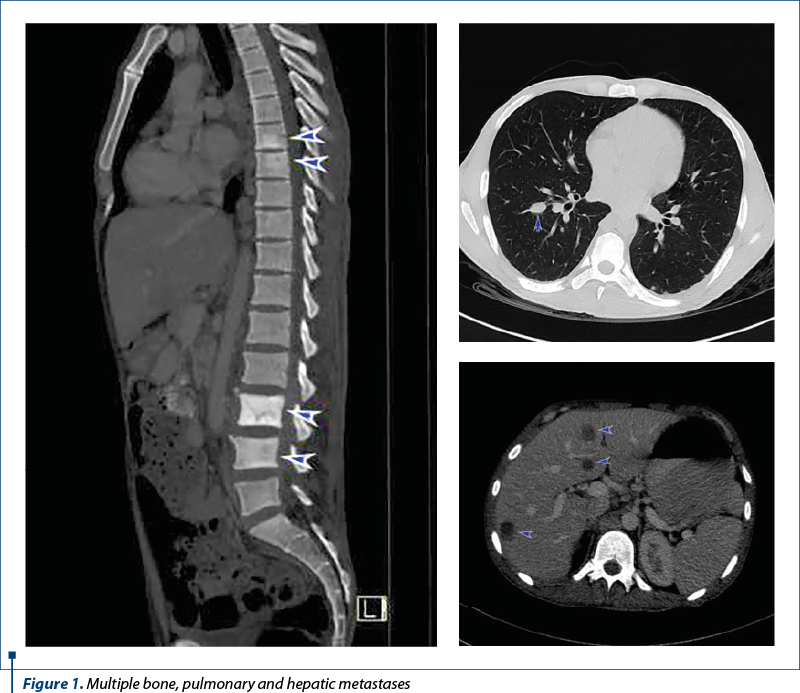

In August 2018, a total spine MRI showed rapidly disease progression with multiple bone metastases (T7, T8, L2, L3, L4, L5), a circumferential paravertebral tumor in the L2-L4 area with intracanalar invasion and significant compression of the filum terminale roots and a left iliac bone metastasis. Bone metastasis had a profound negative impact on the patients’ quality of life, determining important pain and spinal cord compression.

To complete the assessment, it was performed a CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, that showed multiple lung, liver, lymph nodes, retroperitoneal and bone metastases, resulting in further oncological progression.

A neurosurgeon’s opinion was also requested, stating that there is no indication for surgery. The tumor board decided to initiate palliative therapy with gemcitabine, cisplatin and zoledronic acid. Moreover, external radiotherapy was performed in the areas of L3-L4 vertebrae, with a total dose of 16 Gy.

The imaging after 12 courses of chemotherapy showed, in June 2019, a clear numeric and dimensional regression of the pulmonary, hepatic and lymphatic metastases, but the osteolytic lesions seen on the last CT scan were now described as blastic metastases.

The patient had no history of viral infection, but when elevated transaminases were discovered, a hepatitis serology was performed, with the detection of hepatitis C virus antibodies. Hepatitis cytolysis required the suspension from the oncologic treatment for approximatively five months.

After this delay, the tumor board decided to rechallenge with gemcitabine and cisplatin, because the patient did not progress while receiving chemotherapy.

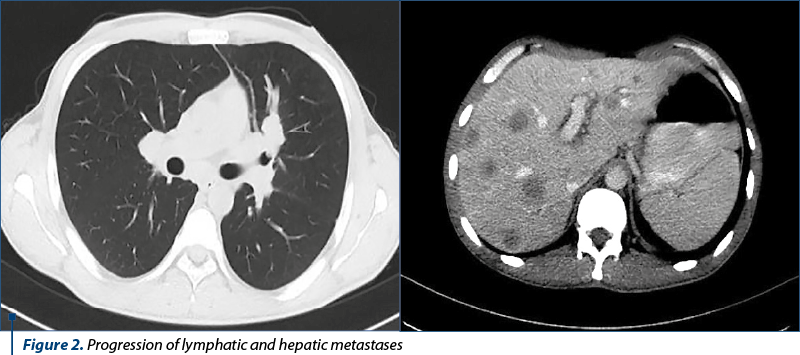

After seven courses of rechallenge therapy, the imagistic assessment demonstrated progressive lymphatic, hepatic and pulmonary metastases, whithout visceral crisis.

Thus, the tumor board decided the initiation of nivolumab flat dose (240 mg) q2w, until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. After three administrations, the patient developed progressive fatigue. A screening evaluation for immunotherapy-induced endocrinopathies was made, and a diagnosis of clinical primary hypothyroidism was established, managed by an endocrinology specialist who recommended substitution therapy with levothyroxine 125 mcg daily. Immunotherapy was not interrupted in the meanwhile.

The next imagistic assessment demonstrated partial response to immunotherapy, with dimensional regression of the pulmonary and lymphatic metastases.

The therapy was continued until the patient developed grade II transaminitis (acording to CTCAE criteria) caused by hepatitis C virus reactivation, with enhanced HCV-RNA viral load.

Thus, the treatment was interruped until liver enzymes normalized.

At present, the patient receives nivolumab, which he tolerates well, with good performance status (ECOG 1), 39 months after starting the initial treatment.

Discussion

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma has a distinct profile compared to other head and neck cancers, in terms of geographical distribution, histopathological subtypes and natural history.

Though rare among Europeans, nasopharyngeal carcinoma is particularly frequent in young adults, and the nonkeratinizing and undifferentiated subtypes are the most common.

This type of cancer is strongly associated with Epstein-Barr virus, but both environmental conditions and genetic predisposition play essential pathological roles(7,8).

A review of young patients (25 years old or younger) with nasopharyngeal carcinoma showed that 93% of the patients had advanced disease at the time of diagnosis.

But, despite the advanced presentation, in young patients the overall prognosis is surprisingly good after the aggressive treatment with concurrent chemoradiotherapy(9).

Moreover, a study using recent data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, assessed the prognosis of patients youger than 30 years of age with nasopharyngeal cancer. Reaserchers showed that younger patients presented with more advanced tumor stages (74.5% stage III/IV versus 63.1% in older patients) and a worse pathological differentiation, but had a better prognosis (p<0.0001)(10).

In nasopharyngeal carcinoma, the bone is the most common site of metastatic disease(11).

Data have shown that the median overall survival in patients diagnosed with metastatic stages is between 10 months to 20 months. But metastasis confined to the bones were associated with longer survival compared to hepatic involvement(12-14).

There are also studies indicating that the incidence of metastases and disease progression may be attributed to the differences in the histopathological patterns. Indeed, patients with nonkeratinizing or undifferentiated carcinomas present a higher risk of early metastases and local advanced tumors at diagnosis, compared to keratinizing cancers(15,16).

As a former smoker, our patient associated an increased risk of cancer, but he had no history of alcohol consumption, human papillomavirus or Epstein-Barr virus infections.

He survived for 39 months from the time the metastatic disease was first diagnosed.

Curative chemoradiotherapy followed by adjuvant sistemic therapy offered a good control of the primary lesion, but bone metastases rapidly occured. Therefore, palliative chemotherapy was needed.

After multiple relapses on platinum-based regimens, the next available category of drugs were the immune checkpoint inhibitors (nivolumab).

In 2016, FDA approved nivolumab for the treatment of recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck that is refractory to platinum-based therapy, based on the CheckMate-141 phase III trial. In this study, nivolumab conferred clinical benefit, with higher overall survival (7.5 months versus 5.1 months) and fewer severe side effects (13.1% versus 35.1%), compared with patients treated with cetuximab, docetaxel or metrotrexate(17).

Unfortunately, patients with nasopharingeal carcinomas were excluded from this trial.

Reconsidering the management of patients with nasopharingeal carcinoma, a recent subanalysis of the CheckMate-141 study evaluated the efficacy of nivolumab in cancer subtypes that were not included in the trial. Compared to histological subtypes assessed in CheckMate-141, in nasopharynx, nivolumab provided similar overall survival and progression-free survival(18).

Another important aspect of our case is represented by the chronic hepatitis C virus infection.

Unfortunately, our patient experienced a significant increase in ALT and AST levels, that required the discontinuation of chemotherapy. The hepatitis C virus reactivation negatively impacted the patients’ oncologic outcomes, with a delay in treatment and disease progression.

The oncological patients with viral hepatitis were frequently excluded from immune checkpoint inhibitors trials, due to the immune-related toxicities and the risk of viral reactivation(19).

In support, some recent studies showed the efficacy of immunotherapy in cancers associated with chronic hepatitis.

Studies evaluating HCV infected patients treated with PD-1 blockade established that nivolumab may potentially increase the production of specific CD8+ T cells and suppress the virus replication(20).

Cancer cells, such as chronic infections too, develop a mechanism to induce the exhaustion of the CD8+ T cells, in order to escape the immune destruction.

Specific CD8+ T cells are expressing high levels of PD1 (programmed death-1) and CTLA4 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4) molecules. Therefore, blocking these molecules can enhance the antiviral reaction and the immune responses(21).

Interestingly, in the CheckMate 040 trial, immune checkpoint inhibitors demonstrated low antiviral activity in some hepatitis C infected patients, with transitory reduction in HCV RNA(22).

In 2020, Pei-Chang Lee and collegues suggested that immune checkpoint inhibitors (nivolumab or pembrolizumab) were safe and not a contraindication in the treatment of advanced hepatocarcinoma and VHB infection. From 62 patients enrolled in this study, there were no HBV reactivations during this therapy(23).

Another recent review, from 2020, supports the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in hepatitis virus C or B infected patients with advanced cancer. The results showed that viral infection did not particularly impact the effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors, and it should not be an obstacle for patients to receive immunotherapy(24).

Moreover, the CheckMate 459 phase III trial, presented at the Virtual ESMO World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer 2020, supported the use of nivolumab, compared with sorafenib, in the first-line therapy of advanced hepatocarcinoma among patients with hepatitis C virus or B virus etiology (the overall survival was significantly higher in the nivolumab arm compared to sorafenib arm: 17.5 versus 12.7 months, HR 0.72, 95% CI, 0.51-1.02 for HCV; and 16.1 versus 10.4 months, HR 0.79, 95% CI, 0.59-1.07, for HBV)(25). In conclusion, HCV infection is not a contraindication for immunotherapy, being an efficient regimen in hepatitis C virus induced hepatocarcinoma.

Furthermore, a retrospective study demonstrated the safety and efficacy of nivolumab in hepatitis C infected patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, compared to noninfected subjects. Nivolumab was well tolerated, with no unexpected toxicity, and the increased levels of transaminases were more likely associated with autoimmune adverse events, because these patients had a stable viral load. Due to similarities of immune alterations in cancer and chronic hepatitis C infection, nivolumab can be a mutually beneficial therapeutic strategy to treat HCV infected cancer patients(26).

Conclusions

This case report highlights the eficacy of using nivolumab in nasopharyngeal carcinoma associated with chronic hepatitis C infection.

Even though there is a low level of evidence regarding immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with viral hepatitis, our patient presented a sustained therapeutic outcome and partial response after four months of immunotherapy.

This potential antiviral benefit derived from checkpoint inhibitors needs to be further observed in our case.

Bibliografie

-

Brennan B. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:23.

-

https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/4-Nasopharynx-fact-sheet.pdf, accessed on 19.12.2021

-

https://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/20/applications/NasopharyngealCarcinoma.pdf, accessed on 19.12.202

-

Liu Z, Chang ET, Liu Q, et al. Oral hygiene and risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma – a population-based case-control study in China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:1201–7.

-

Liu Z, Chang ET, Liu Q, et al. Quantification of familial risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in a high-incidence area. Cancer. 2017;123:2716–25.

-

Chang ET, Liu Z, Hildesheim A, et al. Active and passive smoking and risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a population-based case-control study in southern China. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:1272–80.

-

https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/nasalnasopharyngealgeneral.html, accessed on 29.12.2020

-

Abdulamir AS, Hafidh RR, et al. The distinctive profile of risk factors of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in comparison with other head and neck cancer types. BMC Public Health. 2008 Dec 5;8:400.

-

Cannon T, Zanation AM, Lai V, Weissler MC. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in young patients: a systematic review of racial demographics. Laryngoscope. 2006 Jun;116(6):1021-6.

-

Zhu Y, Song X, Li R, Quan H, Yan L. Assessment of Nasopharyngeal Cancer in Young Patients Aged ≤ 30 Years. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1179.

-

Sun XS, Liang YJ, Liu SL, et al. Subdivision of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients with bone‐only metastasis at diagnosis for prediction of survival and treatment guidance. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51:1259‐1268.

-

Wang CT, Cao KJ, Li Y, Xie GF, Huang PY. Prognosis analysis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients with distant metastasis. Ai Zheng. 2007;26:212‐215.

-

Chen MY, Jiang R, Guo L, et al. Locoregional radiotherapy in patients with distant metastases of nasopharyngeal carcinoma at diagnosis. Chin J Cancer. 2013;32:604‐613.

-

Lin S, Tham IW, Pan J, Han L, Chen Q, Lu JJ. Combined high‐dose radiation therapy and systemic chemotherapy improves survival in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic nasopharyngeal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35:474‐479.

-

Boia ER, Boia M, et al. Non-keratinizing undifferentiated carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2013;54(3 Suppl):839-43.

-

Reddy SP, Raslan WF, et al. Prognostic significance of keratinization in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Am J Otolaryngol. 1995 Mar-Apr;16(2):103-8.

-

Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr, et al. Nivolumab for Recurrent Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N Engl J Med. 2016 Nov 10;375(19):1856-1867.

-

Sato Y, Fukuda N, Wang X, et al. Efficacy of Nivolumab for Head and Neck Cancer Patients with Primary Sites and Histological Subtypes Excluded from the CheckMate-141 Trial. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:4161-4168.

-

Ziogas DC, Kostantinou F, et al. Reconsidering the management of patients with cancer with viral hepatitis in the era of immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2020 Oct;8(2):e000943.

-

Gardiner D, Lalezari, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled assessment of BMS-936558, a fully human monoclonal antibody to programmed death-1 (PD-1), in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. PLoS One. 2013 May 22;8(5):e63818.

-

Pu D, Yin L, Zhou Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with HBV/HCV infection and advanced-stage cancer: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(5):e19013.

-

Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10088):2492–2502.

-

Lee PC, Chao Y, et al. Risk of HBV reactivation in patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor-treated unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. 2020 Aug;8(2):e001072.

-

Pu D, Yin L, Zhou Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with HBV/HCV infection and advanced-stage cancer: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(5):e19013.

-

Sangro B, Park J, Finn R, et al. CheckMate 459: Long-term (minimum follow-up 33.6 months) survival outcomes with nivolumab versus sorafenib as first-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. ESMO World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer 2020 Virtual (1-4 July).

-

Tsimafeyeu I, Gafanov R, Protsenko S, et al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69(9):983–988.