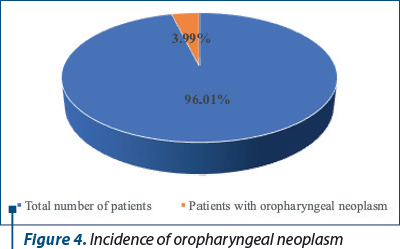

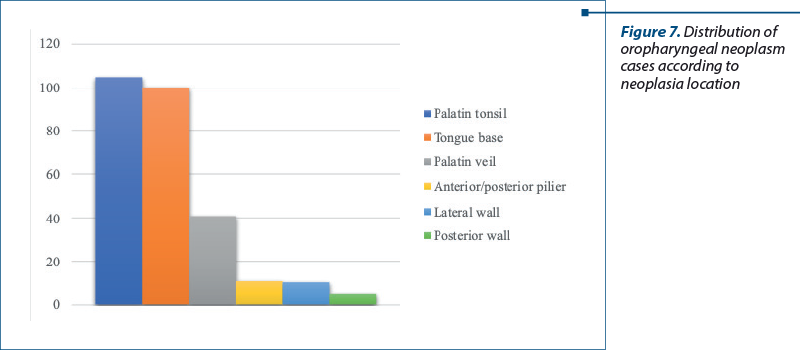

Introduction. Oropharyngeal neoplasm is currently one of the main causes of morbidity worldwide, and patients still present late to the ENT doctor, which limits the therapeutic potential of this pathology. Objective of the study. The permanent follow-up, as closely as possible, of the patients diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm, with their orientation towards the optimal treatment option. Purpose of the study. Establishing a causal relationship between chronic exposure to carcinogens (tobacco, alcohol, areca nuts and human papillomavirus infection) which causes genetic abnormalities in the cells of the oral mucosa, inducing the activation of proto-oncogenes, and inactivation of tumor suppressor genes and genomic instability, the cells changing their rate of growth and multiplication, with the appearance of oropharyngeal cancer. Materials and method. The study analyzed a group of 272 patients hospitalized in the ENT Clinic of the Craiova County Emergency Clinical Hospital, over a period of five years, between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2021, diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm. Results. Between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2021, in the ENT Clinic of the Craiova County Emergency Clinical Hospital, we found that, out of a total number of 6806 hospitalized patients, 272 cases were diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm, resulting in an incidence of 3.99%, most cases of oropharyngeal neoplasms being located at the level of the palatine tonsil, namely 105 cases (38.60%), the next locations being at the base of the tongue (100 cases; 36.76%), at the palatine veil (41 cases; 15.07%), the anterior/posterior pillar (11 cases; 4.04%), at the oropharyngeal lateral wall (10 cases; 3.67%) and the posterior wall of the oropharynx (five cases; 1.83%). Conclusions. The most often asymptomatic character at the onset, the fear of the disease associated with the delay in presenting to the doctor, and the lack of preventive oncological controls make the oropharyngeal neoplasm a dreaded disease, with a reserved prognosis.

The clinical-epidemiological study of oropharyngeal neoplasm – work carried out in the ENT Clinic of the Craiova County Emergency Clinical Hospital

Studiul clinco-epidemiologic al neoplasmului orofaringian – lucrare efectuată în Clinica ORL a Spitalului Clinic Judeţean de Urgenţă Craiova

First published: 30 mai 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ORL.59.2.2023.8110

Abstract

Rezumat

Introducere. Neoplasmul orofaringian reprezintă în prezent una dintre principalele cauze de morbiditate la nivel mondial, iar pacienţii încă se prezintă tardiv la medicul ORL, ceea ce limitează potenţialul terapeutic al acestei patologii. Obiectivul lucrării. Urmărirea permanentă, cât mai atentă, a pacienţilor diagnosticaţi cu neoplasm orofaringian, cu orientarea lor către opţiunea optimă de tratament. Scopul lucrării. Stabilirea unei relaţii de cauzalitate între expunerea cronică la carcinogeni (tutun, alcool, nucile de areca şi infecţia cu papilomavirusul uman) ce determină anomalii genetice la nivelul celulelor mucoasei orale, inducând activarea protooncogenelor, inactivarea genelor supresoare tumorale şi instabilitatea genomică, celulele modificându-şi ritmul de creştere şi multiplicare, cu apariţia neoplasmului orofaringian. Materiale şi metodă. Studiul a analizat un grup de 272 de pacienţi internaţi în Clinica ORL a Spitalului Clinic Judeţean de Urgenţă din Craiova, pe o perioadă de cinci ani, între 1 ianuarie 2017 şi 31 decembrie 2021, diagnosticaţi cu neoplasm orofaringian. Rezultate. În perioada 1 ianuarie 2017 – 31 decembrie 2021, în Clinica ORL a Spitalului Clinic Judeţean de Urgenţă din Craiova am constatat că, dintr-un număr total de 6806 pacienţi internaţi, 272 de cazuri au fost diagnosticate cu neoplasm orofaringian, rezultând o incidenţă de 3,99%. Majoritatea cazurilor de neoplasm orofaringian au fost localizate la nivelul amigdalei palatine (105 cazuri; 38,60%), următoarele localizări fiind la nivelul bazei de limbă (100 de cazuri; 36,76%), al vălului palatin (41 de cazuri; 15,07%), al pilierilor anteriori/posteriori (11 cazuri; 4,04%), al peretelui lateral orofaringian (10 cazuri; 3,67%) şi la nivelui peretelui posterior al orofaringelui (cinci cazuri; 1,83%). Concluzii. Caracterul de cele mai multe ori asimptomatic la debut, frica de boală, asociate cu întârzierea prezentării la medic şi cu lipsa unor controale oncologice preventive, fac din neoplasmul orofaringian o boală de temut, cu prognostic rezervat.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer is a heterogeneous group of tumors affecting the oral cavity, pharynx and larynx, being the sixth most common cancer worldwide, with an estimated annual incidence of over 686,000 cases and with approximately 300,000 deaths(1,2). Approximately 85-90% of head and neck cancers are represented by squamous cell carcinomas(3). Oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer is the fourth most common cancer worldwide, accounting for more than 90% of oral cancers(4,5). In the USA, approximately 49,670 new cases are registered each year, representing approximately 2.9% of all new cancer cases and approximately 9700 associated deaths(6).

Another current issue that we want to emphasize is the permanent follow-up, as closely as possible, of patients diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm, with their orientation towards the optimal treatment option.

Oropharyngeal neoplasias are the most common types of cancer of the head and neck region, being among the top ten of malignancies worldwide. In Romania, the most optimistic statistics give a five-year survival rate of 30%, the cause of this poor prognosis being the delay in diagnosis and, implicitly, of the curative treatment.

It is worth emphasizing that 15% of patients with cancer of the palatine tonsil, when they were examined, presented another cancer in neighboring areas, such as the larynx, esophagus or lung, and 10-40% will develop a second cancer in the second year or later.

The major etiological role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) was proven in 2011. The epidemic increase of OPSCC has been attributed to a significant increase in HPV infection, since HPV causes the most common sexually transmitted infections worldwide. This last public issue is a matter of concern for the entire international community. Based on the European Cancer Observatory (EUCAN) 2012, the highest incidences of OPSCC together with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) in Eastern European countries were reported in Hungary, Slovakia and Romania, while for Western European countries, they were detected in France, Germany and Belgium, and for Northern Europe, they were observed in Denmark and Lithuania, but also in the United States of America(7,8).

OPSCCs are different from OSCCs and are named as HPV-positive or HPV-negative tumors, based on the World Health Organization (WHO) 2017 New Classification of Head and Neck Tumors. The typical locations of HPV-positive OPSCC are the base of the tongue and palatine tonsils. HPV-positive OPSCC have a lower risk of death than HPV-negative cases. The incidence of other secondary tumors or distant metastases is reported to be lower at onset, but they develop later over the next five years, and this implies the responsibility for long-term medical surveillance(9,10).

Materials and method

The study was carried out on a number of 272 (3.99%) cases of carcinomas located at the level of the oropharynx, hospitalized in the Otorhinolaryngology Clinic of the Craiova County Emergency Clinical Hospital between 1.01.2017 and 31.12.2021.

The group of patients was divided according to gender, environment of origin ± alcohol user status ± smoking status, age decade, topographic location of the tumor formation (palatine tonsil/palatine veil/base of the tongue/anterior or posterior pillar/lateral wall/posterior wall), histopathological type, degree of tumor differentiation and TNM staging at the time of diagnosis.

When exploring the patients, we followed the stages of a protocol of methods and investigations that included: anamnesis, signs and symptoms characteristic of oropharyngeal neoplastic disease, clinical examination, paraclinical examination, imaging examination, endoscopic examination, followed by biopsy with the obtaining of tissue specimens that were subjected to histopathological and immunohistochemical examination.

Regarding the anamnesis, it was insisted on questioning regarding the living and working conditions of the studied patients, hereditary-collateral antecedents, personal physiological and pathological antecedents, behaviors (smoking, alcohol etc.). The mostly asymptomatic character at the onset, the fear of the disease associated with the delay in presenting to the doctor, and the lack of preventive oncological controls make the oropharyngeal neoplasm a dreaded disease, with a reserved prognosis.

We extracted the personal data of the patients: name, age, sex, place of origin, insurance category, exposure to toxic substances, that led to the creation of the statistical graphs. The oropharyngeal neoplasm had in most cases an insidious beginning due to minimal functional disorders – a “slight embarrassment in the throat”, so it remained undiscovered for a long time.

Unilateral dysphagia together with odynophagia were the most frequently encountered symptoms in the early stage of oropharyngeal neoplasm. The main clinical manifestations appeared when the tumor spread locoregionally and caught the cervical ganglions, with the appearance of a hard undermandibular angle ganglion most frequently; an acute or subacute episode of the pharynx categorized as “angina” is often found in the patient’s antecedents(11).

The onset was atypical, the patients presenting themselves to the otorhinolaryngologist for trismus (tightening of the pterygoid muscles – the clinical examination was done with difficulty); bleeding (clamping of the anterior pillar and tumor extension); fetid breath, weight loss, entrapment of the inferior alveolar nerve (especially in elderly edentulous patients) or externalization (appearance of adenopathy). When the cervical adenopathy was the initial sign, the tumor was searched meticulously, being able to be hidden in one of the tonsillar crypts.

The entire oral mucosa was systematically examined, the oropharynx was examined using a tongue depressor to be able to visualize both palatine tonsils, the posterior third of the tongue and the soft palate. With the help of the mirror, we examined the base of the tongue, the vallecula and the retronasal space, in such a way as the posterior face of the palatine veil could be visualized(12).

Most of the oropharyngeal neoplasias were located at the level of the palatine tonsils. In the ulcerative form, the tumor was round, with a sacriform appearance, with a diameter of approximately 5-6 mm, with irregular edges, granular bottom and intensely hyperemic; in the vegetative form, the tumor appeared as a red bud, with sessile implantation base and muroform appearance; in the cryptic form, it developed from the covering epithelium of a tonsillar crypt and appeared as a red bud that obstructed the tonsillar crypt; in the form of intercryptal development of the tumor, the tonsil appeared enlarged in volume, being hard. We identified cases of tonsillar neoplasm that presented in a mixed ulcerovegetative form.

In the advanced stages, we identified the palatine tonsil as being highly increased in volume, the patient’s otalgia was constant, and upon palpation it presented a woody hardness. Cancer of the base of the tongue cannot be detected on a superficial examination, its identification being made using the laryngeal mirror and manual palpation of the base of the tongue. In the advanced stages, it was found that tongue mobility disorders occurred, but also a foul breath due to tumor necrosis.

Cancer of the palatine arch was identified almost exclusively on the anterior surface of the soft palate, especially at the level of the anterior pillar, buccopharyngoscopy allowing its identification. Most frequently, we encountered it as an ulceration or as a leukoplakia, rarely in the exophytic form.

Palpation of the tributary nodes of the pharynx was performed: suprahyoid, subhyoid, carotid sulcus, the undermandibular angle nodes usually appearing first.

Panendoscopy, including nasopharyngoscopy, laryngoscopy and tracheobronchoscopy, must be a routine examination in all cases, even though the primary lesion is obvious and its limits are easily defined, knowing that the incidence of secondary occult tumors from primary tumors of the oropharynx is significant.

Results

Incidence of oropharyngeal neoplasm

In the period 1 January 2017 – 31 December 2021, in the ENT Clinic of the Craiova County Emergency Clinical Hospital, we found that, out of a total number of 6806 hospitalized patients, 272 cases were diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm, resulting in an incidence of 3.99%.

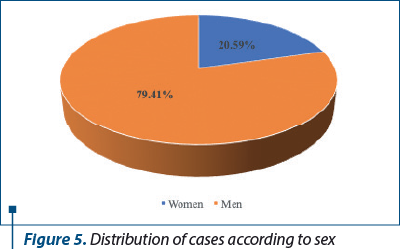

Following the analysis of the gender distribution of patients diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm, we found a number of 216 male patients (approximately 79.41% of the total number of patients) and a number of 56 women, respectively 20.59% of the total number of cases diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm.

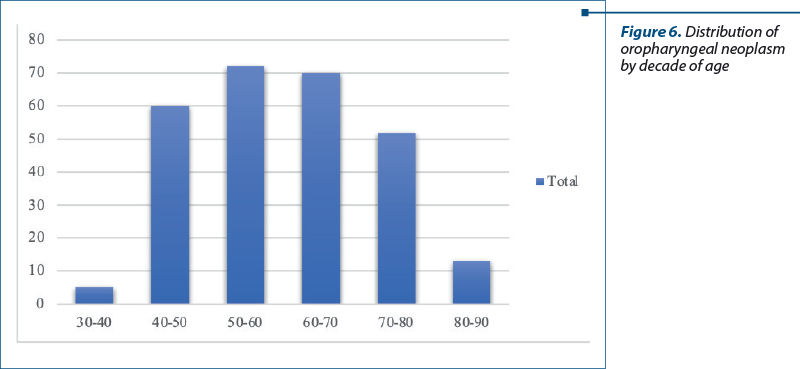

Distribution of oropharyngeal neoplasm cases according to sex by decade of age. Most of the patients were over 50 years old. The 30-40 years old decade had five diagnosed cases (1.83%), of which three men (1.10%) and two women (0.73%), the 40-50 years old decade had 60 diagnosed cases (22.05%), of which 51 men (18.75%) and nine women (3.30%). The decade of 50-60 years old included 72 cases (26.47%), with 57 men (20.95%) and 15 women (5.51%). The decade 60-70 years old included 70 cases (25.73%), with 61 men (22.42%) and nine women (6.98%). The decade of 70-80 years old had a total of 52 cases (19.11%), of which 45 men (16.54%) and seven women (2.57%). The decade of 80-90 years old included 13 cases (4.77%), with nine men (3.30%) and four women (1.47%).

Distribution of oropharyngeal neoplasm cases according to topographic location. Most cases of oropharyngeal neoplasm were located at the level of the palatine tonsil, namely 105 cases (38.60%), the next locations being at the base of the tongue (100 cases; 36.76%), the palatine veil (41 cases; 15.07%), anterior/posterior pillar (11 cases; 4.04%), oropharyngeal lateral wall (10 cases; 3.67%) and the posterior wall of the oropharynx (five cases; 1.83%).

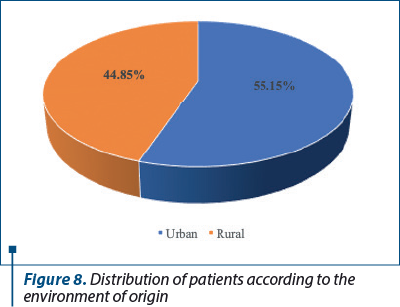

Distribution of patients according to the environment of origin

The patients from the urban environment are more affected by this pathology than those from the rural environment; we found that 150 cases (55.15%) came from the urban environment, while 122 cases (44.85%) came from the rural environment.

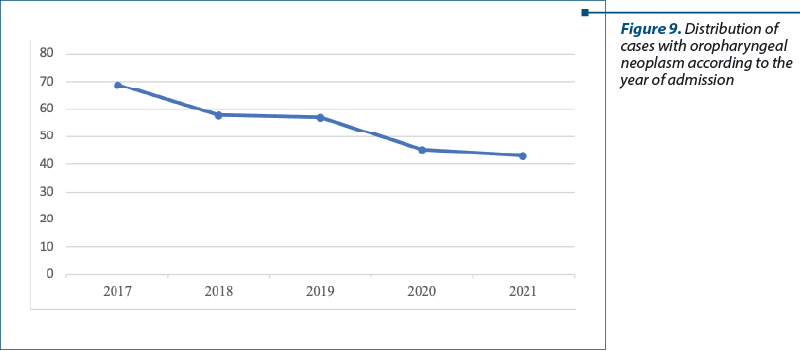

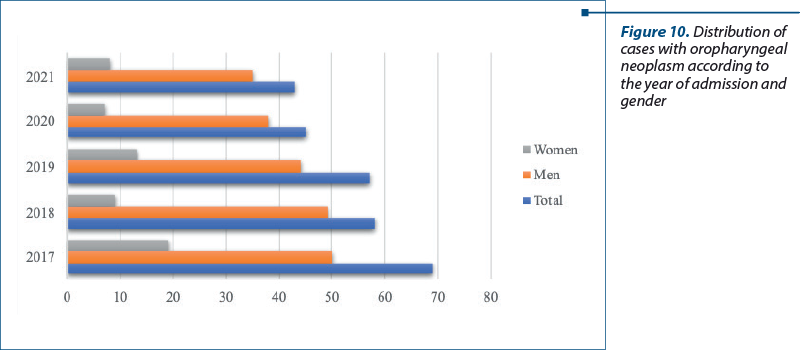

Distribution of patients according to the years studied

In 2017, there were 69 hospitalized cases diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm (25.36% of the total), in 2018 there were 58 cases (21.32%), in 2019 there were 57 cases (20.95%), in 2020 there were 45 cases (16.54%), and in 2021 there were 43 cases (15.80%). We also studied the distribution of cases by year according to sex. In 2017, out of a total of 69 patients, we found 50 men (72.46%) and 19 women (27.53%). In 2018, out of a total of 58 cases, we found 49 men (84.48%) and nine women (15.51%). In 2019, out of a total of 57 cases, 44 were men (77.19%) and 13 were women (22.80%). In 2020, out of a total of 45 cases, 38 were men (84.44%) and seven were women (15.55%). In 2021, out of a total of 43 cases, 35 were men (81.39%) and eight were women (18.60%).

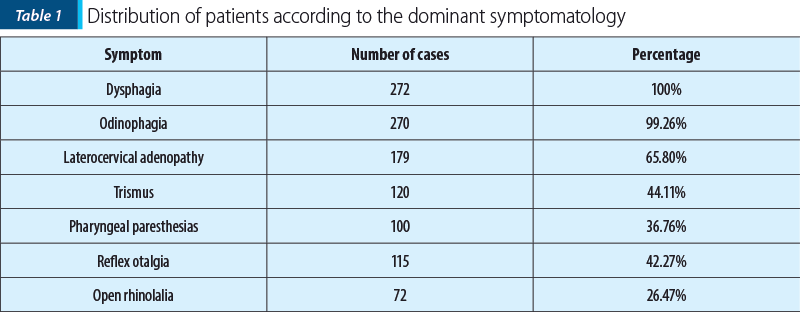

The distribution of oropharyngeal neoplasm cases according to the dominant symptomatology

From the analysis of the observation sheets of patients hospitalized and diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm, we calculated the number of cases and the percentages for each dominant clinical symptom and sign that outline the picture of this pathological entity, and we obtained the following results: most patients presented dysphagia at the time of admission, odynophagia, laterocervical adenopathy, trismus, pharyngeal paresthesias, reflex otalgia and open rhinolalia.

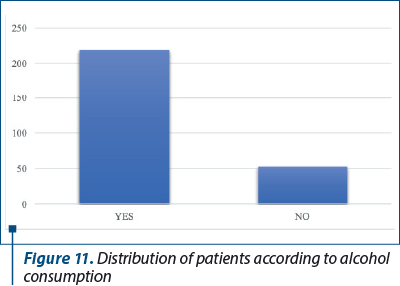

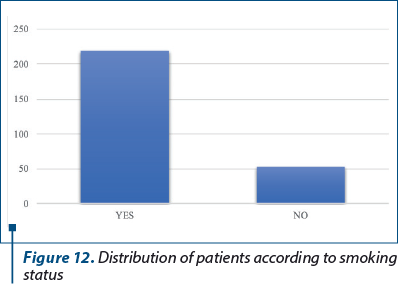

Distribution of patients with oropharyngeal neoplasm according to alcohol and tobacco consumption

The majority of patients stated alcohol consumption – 217 (79.77%) consumed alcohol and 55 (20.22%) denied alcohol consumption; 219 (80.51%) were smokers and 53 (19.48%) denied smoking.

Discussion

In the period 1 January 2017 – 31 December 2021, in the ENT Clinic of the Craiova County Emergency Clinical Hospital, we found that, out of a total number of 6806 hospitalized patients, 272 cases were diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm, resulting in an incidence of 3.99%.

Most cases of oropharyngeal neoplasm were located at the level of the palatine tonsil, namely 105 cases (38.60%), the next locations being at the base of the tongue (100 cases; 36.76%), the palatine veil (41 cases; 15.07%), anterior/posterior pillar (11 cases; 4.04%), oropharyngeal lateral wall (10 cases; 3.67%) and the posterior wall of the oropharynx (five cases; 1.83%).

Most of the patients were represented by those over 50 years old. The decade of 30-40 years old had five diagnosed cases (1.83%), in the decade of 40-50 years old we had 60 diagnosed cases (22.05%), the decade of 50-60 years old included 72 cases (26.47%), the decade of 60-70 years old included 70 cases (25.73%), the decade of 70-80 years old had a total of 52 cases (19.11%), and the decade of 80-90 years old included 13 cases (4.77%).

Following the analysis of the gender distribution of the patients diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm, we found a number of 216 male patients (approximately 79.41% of the total number of patients) and a number of 56 women, respectively 20.59% of the total number of cases diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm.

The patients from the urban environment are more affected by this pathology than those from the rural environment; we found that 150 cases (55.15%) came from the urban environment, while 122 cases (44.85%) came from the rural environment.

Regarding the distribution of patients according to the years studied, in 2017 there were 69 hospitalized cases diagnosed with oropharyngeal neoplasm (25.36%), in 2018 there were 58 cases (21.32%), in 2019 there were 57 cases (20.95%), in 2020 there were 45 cases (16.54%) and in 2021 there were 43 cases (15.80%), which shows us that, during the entire duration of the COVID-19 pandemic, the addressability to the doctor was reduced.

Most patients presented dysphagia, odynophagia, laterocervical adenopathy, trismus, pharyngeal paresthesias, reflex otalgia and open rhinolalia at the time of admission to the ENT Clinic.

The majority of patients stated alcohol consumption; 217 (79.77%) consumed alcohol and 55 (20.22%) denied alcohol consumption; 219 (80.51%) were smokers and 53 (19.48%) denied smoking.

Direct HPV testing for E6/E7 messenger DNA or RNA is done by in situ hybridization (ISH) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Indirect HPV testing is done by immunohistochemistry (IHC) by identifying the expression of the tumor suppressor protein p16. According to the systematic review and expert consensus, high-risk HPV screening for all new patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma (OPSCC), either from the primary tumor or from cervical nodal metastases, using p16 IHC is recommended, but not routinely recommended for other head and neck carcinomas. p16 overexpression is a stable and reliable surrogate marker of HPV-mediated carcinogenesis, but only for oropharyngeal localization, with a sensitivity of 96.8% and a specificity of 83.8%. It is also a major positive prognostic marker of OPSCC. The pathologists must report tumors as HPV positive or p16 positive(13).

Current recommendations in the US and Europe apply to both HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPSCC, according to staging. Primary surgery (transoral or open resection of the tumor with or without cervical dissection) or definitive radiotherapy is recommended in early stages (T1/2, N0/1). It is very encouraging that the results are good for all patients with HPV-positive tumors, regardless of the type of unimodal treatment they received, with similar local disease control and with over 85% survival rate. On the other hand, p16-positive OPSCCs must have a better survival and response to multimodal treatment (chemoradiation) than HPV-negative tumors. A multidisciplinary medical board is needed and must include a dietitian and a speech/swallowing therapist to provide a wide range of recommendations for various clinical circumstances and patients’ preferences(14).

Conclusions

1. The most often asymptomatic character at the onset, the fear of the disease associated with the delay in presenting to the doctor, and the lack of preventive oncological controls make the oropharyngeal neoplasm a dreaded disease, with a reserved prognosis.

2. More and more studies show that chronic exposure to carcinogens causes genetic abnormalities in the cells of the oral, pharyngeal and laryngeal mucosa; these genetic anomalies determine the activation of proto-oncogenes and the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes, the cells proliferating chaotically, due to an aberrant control of the cell cycle(15).

3. The identification and elimination of risk factors involved in the etiopathogenesis of oropharyngeal tumors have an essential role in reducing the incidence of oropharyngeal tumor lesions. Classified into exogenous and endogenous (less known), the risk factors involved in the etiology of oropharyngeal neoplasm are: smoking, alcohol consumption, papillomaviruses (HPV), food and polluting substances (radon, asbestos).

4. Despite progress in understanding the disease and improved therapeutic interventions, the oropharyngeal neoplasm continues to be diagnosed at an advanced stage, and the survival rate remains low. The financial cost of treating this condition can be the highest of all cancers in the USA, and survivors often suffer major impairments in the quality of life.

5. Like other researchers(16,17), we also believe that the main risk factor for oropharyngeal cancer is smoking, because tobacco contains approximately 50 types of carcinogenic substances capable of producing changes in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), being in direct contact with the mucous membrane of the oral cavity during smoking(18-20). Numerous studies have shown that approximately 75% of HNC cases are caused by smoking and alcohol consumption(21). Other studies have shown that the risk for oral cancer drops by about 35% one to four years after quitting smoking and by about 80% twenty years after quitting. Even after the diagnosis of oral cancer, quitting smoking is important to improve the survival rate; patients who continue to smoke have a higher risk of cancer recurrence and show a weaker response to treatment than those who quit smoking(22).

Acknowledgment: This work was supported by the grant POCU/993/6/13/153178, “Performanţă în cercetare” (“Research performance”), co-financed by the European Social Fund within the Sectorial Operational Program Human Capital 2014-2020.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

-

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90.

-

Bălică NC, Poenaru M, Ştefănescu EH, Boia ER, Doroş CI, Baderca F, Mazilu O. Anterior commissure laryngeal neoplasm endoscopic management. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2016;57(2 Suppl):715–718.

-

Belcher R, Hayes K, Fedewa S, Chen AY. Current treatment of head and neck squamous cell cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110(5):551–574.

-

Warnakulasuriya S. Living with oral cancer: epidemiology with particular reference to prevalence and life-style changes that influence survival. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(6):407–410.

-

Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(4):212–236.

-

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30.

-

Taberna M, Mena M, Pavón MA, Alemany L, Gillison ML, Mesía R. Human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2386–2398.

-

Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4294–4301.

-

Katabi N, Lewis JS. Update from the 4th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumours: what is new in the 2017 WHO Blue Book for tumors and tumor-like lesions of the neck and lymph nodes. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11(1):48–54.

-

Sood AJ, Mcllwain W, O’Connell B, Nguyen S, Houlton JJ, Day T. The association between T-stage and clinical nodal metastasis in HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. Am J Otolaryngol. 2014;35(4):463–468.

-

Radu C. Tratamentul chirurgical al cancerului de amigdala palatină. Editura Conphis, Râmnicu Vâlcea, 2002.

-

Manu A. Chirurgie oncologică ORL şi cervico-facială. Editura Hamangiu, Bucureşti, 2020.

-

Gargano JW, Unger ER, Liu G, Steinau M, Meites E, Dunne E, Markowitz LE. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus in males, United States, 2013–2014. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(7):1070–1079.

-

Brotherston DC, Poon I, Le T, Leung M, Kiss A, Ringash J, Balogh J, Lee J, Wright JR. Patient preferences for oropharyngeal cancer treatment de-escalation. Head Neck. 2013;35(2):151–159.

-

Mogoanţă CA. Studiul clinic, histologic şi imunohistochimic al proceselor de metaplazie şi neoplazie de la nivelul cercului limfatic Waldayer. PhD Thesis, 2009.

-

Gandini S, Botteri E, Iodice S, Boniol M, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Boyle P. Tobacco smoking and cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(1):155–164.

-

Ciolofan S, Ioniţă E, Mogoanţă CA, Popescu FC, Anghelina F, Chiuţu L, Stanciu G. Malignant melanoma of nasal cavity. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011;52(2):679–684.

-

Danaei G, Vander Hoorn S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M; Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group (Cancers). Causes of cancer in the world: comparative risk assessment of nine behavioural and environmental risk factors. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1784–1793.

-

Gillison ML. Current topics in the epidemiology of oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. Head Neck. 2007;29(8):779–792.

-

Ram H, Sarkar J, Kumar H, Konwar R, Bhatt ML, Mohammad S. Oral cancer: risk factors and molecular pathogenesis. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2011;10(2):132–137.

-

Warnakulasuriya S. Living with oral cancer: epidemiology with particular reference to prevalence and life-style changes that influence survival. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(6):407–410.

-

Gray JL, Maghlouth AA, Hussain HA, Sheef MA. Impact of oral and oropharyngeal cancer diagnosis on smoking cessation patients and cohabiting smokers. Tob Induc Dis. 2019;17:75.