Rheumatic diseases, through the chronic immune inflammation that defines their individualized evolutionary course, can induce emergency-type, sometimes life-threatening events. Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is a rare but life-threatening complication that can occur most frequently as an onset manifestation, sometimes during the course of the disease, years after onset, but possibly, less frequently, even in remission. It most commonly affects patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (Still’s disease). The inducing triggers are diverse, but most commonly infection is involved. Consequently, the diagnosis may be delayed by the similarity of symptoms sometimes to sepsis or to the flare appearance of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The use of specific MAS criteria (EULAR-ACR-PRINTO, 2016) facilitates early diagnosis, essential especially for severe forms in which prompt anticytokinetic therapeutic intervention can save the patient’s life. In its absence, there may be a risk of nonresponse to other therapies such as cortisone pulse therapy, remitting and immunosuppressive medication, or immunoglobulin.

Emergencies in pediatric rheumatology (I) – macrophage activation syndrome

Urgenţe în reumatologia pediatrică (I) – sindromul de activare macrofagică

First published: 30 aprilie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Pedi.69.1.2023.7981

Abstract

Rezumat

Bolile reumatismale, prin inflamaţia cronică imună care le defineşte parcursul evolutiv individualizat, pot induce evenimente de tip urgenţă, uneori ameninţătoare de viaţă. Sindromul de activare macrofagică (SAM) este o complicaţie rară, dar cu risc vital, care poate surveni cel mai frecvent ca manifestare de debut, uneori pe parcursul evolutiv, după ani de la debutul, posibil însă şi mai rar, chiar în faza de remisiune a bolii. Cel mai frecvent afectează pacienţii cu artrită juvenilă idiopatică în forma sistemică (boala Still). Factorii declanşatori sunt diverşi, dar cel mai frecvent infecţia este cea implicată. În consecinţă, diagnosticul poate fi întârziat prin similitudinea simptomatologiei uneori cu sepsisul sau asemănătoare puseului acut din artrita juvenilă idiopatică. Utilizarea criteriilor specifice MAS (EULAR-ACR-PRINTO, 2016) facilitează diagnosticul precoce, esenţial mai ales pentru formele severe, la care intervenţia terapeutică anticitokinică promptă poate salva viaţa pacientului. În absenţa acesteia, există riscul lipsei de răspuns la alte terapii, precum pulsterapia cortizonică, medicaţie remisivă şi imunosupresoare sau imunoglobulina.

Introduction

Rheumatic diseases, through the chronic immune inflammation that defines their individualized evolutionary course, can induce emergency-type, sometimes life-threatening events. Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is a rare but life-threatening complication that can occur in rheumatic diseases, most commonly as an onset manifestation, often during the course of the disease, years after onset, but possibly, less frequently, even in remission. It most commonly affects patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (Still’s disease), but cases of systemic lupus, Kawasaki vasculitis and periodic fever have been reported. Also, MAS can be associated with a variety of other pathologies such as neoplasms, infections (e.g., EBV) or primary immunodeficiency, but with a lower incidence compared to rheumatic diseases. Its clinical-biological expression may be partially superimposable on the onset picture of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) or sepsis, which delays the diagnosis and the appropriate treatment, putting the patient at risk.

Clinical case

The patient S.M., male, 8 years old, from Iaşi county, presented in the Emergency Unit of the “Sf. Maria” Emergency Clinical Hospital for Children, Iaşi, for fever (T max. 39ºC) accompanied by pain in the lower abdominal floor. From the personal pathological history, we mention that he was diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), in systemic form, at the age of 4 years old, a form that later evolved to seronegative polyarticular subtype, under initial treatment with nonsteroidal nonselective anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The patient was noncompliant to pulsations with methylprednisolone, and under remission treatment with methotrexate (>9 months) hematotoxicity was objectified, for which it was discontinued. At this stage, it was decided to initiate therapy with anti TNF-alpha biologic agents (etanercept) – the only one available at that time in Romania, under which he developed an allergic reaction, the parents subsequently refusing the therapy. The patient subsequently followed treatment with sulfasalazine and medrol ± NSAIDs, incorrectly and discontinuously administered, rarely presenting at regular check-ups.

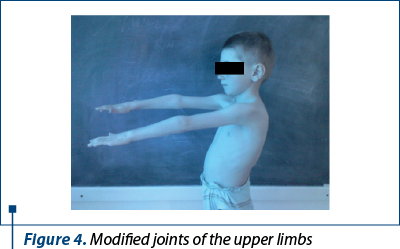

Clinical exam: height 113 cm (-2.41 SD), weight 16.5 kg (-4.18 SD), mucocutaneous pallor, joint stiffness and bilateral movement impairment in the knee, tibio-tarsal, hip and radiocarpal joints, swelling of the knees, tibio-tarsal and radio-carpal bilaterally (Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4), VAS joint pain 6/10 (Figure 5), AV 80/min., BP 90/55 mmHg, FR 16/min., Sat O2 99%, cardiopulmonary and neurologicalally normal, liver and spleen within normal limits.

Investigations: Hb 11g/dl, GA 23,340/mmc, Tr 304,000/mmc, PN 79.1%, L 14.2%, M 6.5%, E 0.1%, VSH 69 mm/1 h, Fg 988 mg/dl, RF absent, TGP 14 IU, TGO 18 IU, blood glucose 72 g/l, urea 0.22 g/l, PT 62.8 g/l, serine 55.9%, 1-6%, 2-18.1% , b1 9.7%, b2 4.7%, у 5.6%. Urine exam – normal; ENT – discrete pharyngeal congestion; Chest X-ray – normal; the ophthalmological exam for uveitis was normal.

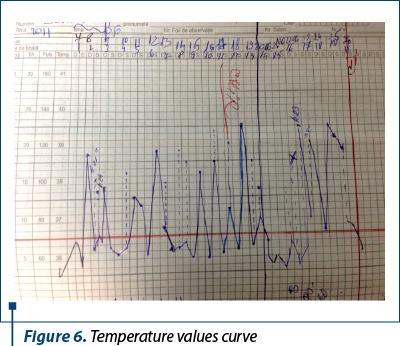

The evolution was progressively unfavorable; after 48 hours, the patient had persistent pain in the lower abdominal floor associated with septic fever and dyspeptic syndrome. Surgical consultation revealed an acute abdomen and the patient was transferred to the Pediatric Surgery Clinic for appendectomy. Postoperatively, he maintained the septic fever but peritoneal fluid culture, blood culture and urine culture were negative. The investigations revealed: Hb 10.1 g/dl, Ga 26,180/mmc, TR 322,000/mmc, PN 89.8%, L 6%, M 2.7%, E 1.1%; VSH 89 mm/1 h, Fg 917 mg/dl, Fe 34 µg/dl. The postoperative abdominal ultrasound was normal and the EKG was normal. Echocardiography – minimal pericardial reaction, 3-4 mm. Treatment with Tienam®, Targocid®, fluconazole, hydroelectrolytic and acid-base rebalancing, Salazopyrine®, PPI and antithermics was initiated. After 10 days, he was transferred to the Pediatric Clinic 2, with maintenance of high temperature values (Figure 6).

Investigations: Hb 9.8g/dl¯, Ga 15,270/mmc, TR 256,000/mmc, PN 87.3%, L 9.1%, M 3.6%, elevated seric ADA, 71 Ui/ml; VSH 40,mm/1 h, Fg 580mg/dl; blood glucose, hepato-renal function normal; IgG and IgA immune deficiency; IDR 2 IU PPD negative. Chest X-ray – normal image. Medulogram – normal granulopoiesis, erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis; secretory plasmacytosis; BK culture (gastric swab) and Quantiferon test – normal values.

At this stage, it was decided to administer pulses of methylprednisolone in combination with sulfasalazine, immunoglobulin i.v. 500 mg/kg, hydroelectrolytic rebalancing and proton pump inhibitors (PPI). However, the general condition progressively deteriorated on the 17th postoperative day, the patient in afebrile condition had intermittent knee and bilateral tibio-tarsal arthralgia, hepatosplenomegaly 3 cm below the rim, watery stools, postural vomiting initially, later in “coffee grounds”, cold extremities, low pulse, AV 98/min, BP 80/40 mmHg, arrhythmic heart, FR 20/min and Sat O2 94%. It was decided to transfer him to the intensive care unit (ICU) for monitoring.

The ICU investigations show rapid multisystemic degradation, coagulation abnormalities, leukocytosis and anemia: Hb 9.7 g/dl, Ga 56,120/mmc, TR 98,000/mmc, HT 41.5%, R 0.26%, PN 80.8%, L 16.7%, M 0.7%, E 0.5%, VSH 10 mm/h, Fg 200 mg/dl, TGP 580, TGO 749 UI, urea 65 mg/dl, creatinine 0.85 mg/dl, blood glucose 112 mg/dl, BT 1.79, BD 1.10, BI 0.69 mg/dl, CRP 94.78 mg/dl, RA 17.47, Na 127, K 5.04, Cl 94 mmol/l; T Quick 25.9 s, prothrombin activity 46%, INR 1.63, APTT 64.5. Urinalysis – intensely hyperchromatic (dark green), sediment: rare leukocytes, amorphous urates, rare hyaline cylinders, protein 30 mg/dl, bilirubin 1 mg/dl, urobilinogen 12 mg/dl, ketone bodies absent, density 1025, pH 5.5. Chest and abdominal X-ray – normal. Cardiorespiratory arrest occurred, which did not respond to resuscitation maneuvers, and death was subsequently declared.

The pathological examination revealed meningocerebral edema, pneumonia with serofibrinous pleurisy in the right lower lobe; alveoli with numerous macrophages, pericarditis (30 ml), hemorrhagic endomyocarditis (inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes, plasma cells, PMN, macrophages), hepatosplenomegaly (inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes, plasma cells, PMN, macrophages); frequent inflammatory nodular lesions in liver lobe, renal degeneration, mesenteric micropolyadenopathy and congestive gastritis.

Particularity of the case: a young patient diagnosed with JIA, systemic form, and seronegative polyarticular evolution in whom no disease control was obtained, on the one hand, by adverse reaction to medication, and on the other hand, by personal noncompliance with medical recommendations, and who associated during the evolution (four years from the time of diagnosis) MAS in severe form, with impaired vital prognosis.

Discussion

Most commonly, macrophage activation syndrome is associated with systemic JIA. Its severity varies, about 10% of patients may have a severe or fulminant form, with high life-threatening risks, but 30% may associate subclinical/mild or moderate manifestations of MAS. The clinical picture is of a “pseudo-sepsis” with prolonged fever, possible hepatosplenomegaly and adenomegaly, cutaneo-mucosal hemorrhagic elements, sometimes with severe neurological impairment in which the patient presents convulsions or even coma, and extensive systemic impairment (cardiopulmonary and renal)(1). Since arthritis is less evident or “apparently” improves in all these clinical manifestations, the risk of not early evoking the diagnosis of MAS is major. The biological criteria to support the diagnosis were established in 2016 by the European and American Societies of Rheumatology (EULAR; ACR) and Pediatric Rheumatology (PRINTO) and include hyperferritinemia (>684 mg/ml) plus two of the following criteria: thrombocytopenia, hepatocytosis syndrome, hypertriglyceridemia (>156 mg/dl) or fibrinogen (≤360 mg/dl). The inflammatory syndrome may be absent at onset. Previous diagnostic criteria were used in the diagnosis of lymphohistiocytic hemophagocytic syndrome (HLH) since 2004, which are much more extensive, involving the histopathological demonstration of medullary (CD163) or splenic or lymph node macrophagocytic hemophagocytosis (may be lacking in the initial phase and lacks specificity/sensitivity for MAS), elevated sIL2R (sCD 25 >2400 IU/ml) and sCD163 values, and low or absent LT-NK activity, pancytopenia, and more severe values of other biological criteria. Consequently, the risk of diagnostic error or delay is high, especially in mild or less severe forms at onset(2).

The existence of these criteria is beneficial in supporting a positive diagnosis, but also in differentiating SAM from the flare periods of JIA. The etiology of MAS is not currently elucidated, but there are numerous triggers cited that may induce it against a preexisting background of chronic immune inflammation (infections, operative stress, trauma etc.). Although the genetic component is now firmly established in familial forms of lymphohistiocytic hemophagocytic syndrome (HLH), however 40% of secondary forms of HLH associate heterozygous mutations. The pathogenic mechanism is related, on the one hand, to the activation of the macrophage proinflammatory phenotype and, implicitly, to the increased synthesis of some cytokines (IL6, IL1, IL18, TNF) that maintain the immune inflammatory cascade, and on the other hand, with the functional imbalance created between LT-NK (native immunity) whose deficient activity determines the persistence of antigenic stimulation by delaying the destruction of dendritic cells and overstimulating LT-CD8 (adaptive immunity) promoters of the inflammatory immune cascade(3). LT-NK malfunction seems to be induced by some genetic defects inducing altered synthesis of cellular cytolytic lymphocyte proteins, such as perforins, and causing disruption of apoptosis of macrophages, lymphocytes and infected cells. As a result, the therapeutic target is cytokine blockade by anti-cytokine monoclonal Ac or receptor antagonists: aIL1 R (anakinra, canakinumab), anti-IL6R (tocilizumab), CTLA4Ig (CD28/abatacept), Jak1/2 (Janus-kinase inhibitor, tofacitinib)(4,5). The classical therapeutic approach include cortisone pulse therapy (methylprednisolone), but to which many patients may be nonresponders, with risk on vital prognosis impairment; i.v. immunoglobulins, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine A (with very good results), plasmapheresis; etoposide, with good results, especially when the trigger was the EBV infection. Stem cell transplantation is the only one that, in extremis, can ensure survival in familial forms of HLH.

The presented case falls into the AJI risk group for MAS – i.e., the systemic subtype that evolved to seronegative polyarticular type. The triggering factors for the onset were loss of disease control through adverse drug reaction to methotrexate, and allergic reaction to anti-TNF-alpha agents (the only ones in use in JIA on the national protocol at that time) and, also, family noncompliance to i.v. methylprednisolone. Moreover, the patient followed intermittently the recommended background treatment (NSAIDs, sulfasalazine, oral Medrol®). Prolonged febrile syndrome associated with acute painful surgical abdomen delayed the diagnosis of MAS, the operative stress being itself another trigger for this severe complication(6). The patient also associated a polyclonal immune deficiency which increased the risk of infectious complications, likely triggering MAS in the setting of therapeutically uncontrolled JIA. Despite therapy with methylprednisolone associated with sulfasalazine and i.v. immunoglobulin, the patient developed a severe form of MAS, resulting in his death by multiorgan failure and fatal heart rhythm disturbances. Subsequently, the histopathological examination confirmed multiorgan MAS. Currently, there are situations that can evolve to this complication with impact on vital prognosis even though JIA was under an apparent clinical-biological control and in which, unfortunately, we do not always have at hand the anticytokine intervention drugs recommended by the guidelines to stop the inflammatory cascade and its fatal evolution(7).

In conclusion, macrophage activation syndrome represents an emergency in rheumatic diseases which in their severe forms affect the vital prognosis of the patient and which can constitute a diagnostic trap in mild and moderate forms, due to its similarity to other pathologies and/or the “flare” aspect of JIA. Consequently, early diagnosis and aggressive treatment, as well as multidisciplinary team care, must be a priority.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY

Bibliografie

- Crayne CB, Albeituni S, Nichols KE, Cron RQ. The Immunology of Macrophage Activation Syndrome. Front Immunol. 2019;10:119.

- Ravelli A, Minoia F, Davi S, Horne A, Bovis F, Pistorio A, et al. 2016-Classification criteria for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology/Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation Collaborative Initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:481–9.

- Minoia F, Davi S, Horne A, Bovis F, Demirkaya E, Akikusa J, et al. Dissecting the heterogeneity of macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:994–1001.

- Jenkins MR, Rudd-Schmidt JA, Lopez JA, Ramsbottom KM, Mannering SI, Andrews DM, et al. Failed CTL/NK cell killing and cytokine hypersecretion are directly linked through prolonged synapse time. J Exp Med. 2015;212:307–17.

- Das R, Guan P, Sprague L, Verbist K, Tedrick P, An QA, et al. Janus kinase inhibition lessens inflammation and ameliorates disease in murine models of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2016;127:1666–75.

- Cron RQ, Davi S, Minoia F, Ravelli A. Clinical features and correct diagnosis of macrophage activation syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015;11:1043–53.

- Sonmez HE, Demir S, Bilginer Y, Ozen S. Anakinra treatment in macrophage activation syndrome: a single center experience and systemic review of literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37:3329–35.