In recent years, psychedelic substances have returned to the attention of researchers, considering the possibility of representing new therapeutic options used in the treatment of various mental disorders. However, the neurobiological mechanisms that explain the therapeutic effects of psychedelics are not fully known. Mental disorders – especially affective disorders and anxiety disorders – represent an important burden for the entire health system. Psychotropic medication has a series of limitations, including numerous adverse effects, therefore there is a permanent need to discover new therapeutic options. Such a therapeutic option can be represented by the use of psychedelic substances, which have antidepressant, anxiolytic, anti-suicidal and even anti-addictive effects. This recent attention paid to psychedelic substances has led to an increase in tourism with the purpose of using psychedelics, which aims to treat various somatic diseases, mental disorders, or even psychological problems. Additionally, there is an increased interest and even hopes related to the acceptance and approval of psychedelics as a pharmacological choice for the treatment of various mental disorders.

Psychedelic substances – a new therapeutic option for mental disorders?

Pot fi substanţele psihedelice o nouă opţiune terapeutică pentru tulburările psihice?

First published: 23 aprilie 2024

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.76.1.2024.9463

Abstract

Rezumat

În ultimii ani, substanţele psihedelice au revenit în atenţia cercetătorilor, avându-se în vedere posibilitatea ca acestea să reprezinte noi opţiuni terapeutice utilizate în tratamentul diferitelor tulburări psihice. Cu toate acestea, mecanismele neurobiologice care să explice efectele terapeutice ale psihedelicelor nu sunt pe deplin cunoscute. Tulburările psihice, în special de tipul tulburărilor afective şi de anxietate, reprezintă o povară importantă pentru întregul sistemul de sănătate. Medicaţia psihotropă are o serie de limitări, inclusiv numeroase efecte adverse, de aceea există o nevoie permanentă de a descoperi noi alternative terapeutice. O astfel de opţiune terapeutică poate fi reprezentată de utilizarea substanţelor psihedelice, care au efecte antidepresive, anxiolitice, antisuicidare şi chiar antiadictive. Această atenţie acordată în ultima perioadă substanţelor psihedelice a făcut să amplifice şi turismul pentru utilizarea psihedelicelor, având drept scop tratarea diferitelor afecţiuni medicale, psihice sau a unor probleme psihologice. Suplimentar, există un interes crescut şi chiar speranţe legate de acceptarea şi aprobarea psihedelicelor ca opţiune farmacologică pentru tratarea diferitelor tulburări psihice.

The term “psychedelic” originates from the Greek words psyche, which means soul, and delos, which means to show. The term “psychedelic substance” was used for the first time in 1956, by psychiatrist Humphry Osmond, who was conducting research on lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)(1).

The main psychedelic substances still studied today have had a significant value since ancient times, being used as entheogenic substances for spiritual or shamanic rituals in Central and South America.

Psychedelics can be classified into three major categories, namely tryptamines, phenethylamines, and lysergamides. These were also classified as illegal substances, which led to the stigma and persistent negative perception of psychedelics, as well as their constant denigration and criminalization. However, in recent years, information and clinical studies have begun to appear regarding the role of psychedelics in the treatment of mental disorders, such as alcohol and tobacco addiction, mood and anxiety disorders, or in depression associated with severe oncological conditions. Thus, in 2019, Food and Drug Administration has approved the use of Spravato®, a ketamine analog developed by Johnson and Johnson for treatment-resistant depression. Also, psilocybin is in the process of being approved as a “breakthrough therapy” for major depressive disorder, through the companies Compass Pathways Ltd. (2018) and the Usona Institute (2018)(1,2). Psychedelics can also be used in the psychotherapeutic process. Psychotherapy assisted by psychedelics, in addition to classical psychotherapy, involves a preparation phase, an actual treatment phase and, later, an integration phase of the lived experience. In order to minimize the negative experiences during psychotherapy, a more careful screening of patients who can benefit from this type of psychotherapy should be considered(2,3). The patient will require a more careful monitoring regarding the possible physiological and psychological effects that may appear during the therapy assisted by psychedelics, with the involvement of doctors, psychologists and therapists. Additionally, the patient will be offered a session aimed at assisting in processing the lived experience and at obtaining an adequate perspective from this therapy. For a more careful monitoring of the obtained results, it has been proposed to measure them with certain evaluation scales, but many clinical evaluation tools available so far demonstrate a high variability and a low sensitivity and/or specificity in psychedelic-assisted therapy(2,4).

The researchers identified the patients who are not eligible for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, namely:

-

people with a personal or family history of psychotic disorder;

-

people diagnosed with cardiovascular diseases (for example, hypertension, tachyarrhythmias);

-

people receiving therapy with SSRIs, lithium, antipsychotics and MAOIs.

All of the studies did not include pediatric populations or older adults(2).

In 2010, the UK Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs analyzed data on 20 substances with potential for abuse, in order to indicate the level of risk represented by auto- or heteroaggression. It is used a score from 0 to 100, a higher score indicating a greater risk of morbidity, mortality and dependence for a given substance. Thus, alcohol has the highest score, with a value of 72, heroin and cocaine have a moderate risk (value of 55 and 27, respectively), and hallucinogens, such as ketamine, MDMD or LSD, have a low risk (15, 9, and, respectively, 7)(5).

The use of psychedelics in the treatment of mental disorders implies a series of benefits. Thus, the researchers indicate that, unlike traditional psychopharmacological options, the onset of action of psychedelics appears to be significantly faster. Most promising are the initial data from a study demonstrating a strong dose-response relationship, with sustained benefits, such as a single dose of psilocybin reduce the symptoms of depression and anxiety for up to one year(6,7).

Psychedelics are generally well tolerated, and the adverse effects are relatively minor and persist for a short period after administration (less than 72 hours). However, clinical research remains limited, the studies performed are not randomized or double-blind, and most of them have a small population sample size and relatively short duration of treatment and follow-up period. Most of the available studies provide limited insight into the adequate dose that can be used, the therapeutic response or efficacy, and they have focused, above all, on determining the appropriate dose regarding the safety of administration of the psychedelics(8,9).

Many studies refer to the use of psychedelics in combination with psychotherapy, with the participation of well-trained and experienced personnel. But psychotherapy is traditionally considered a first-line treatment for many mental health conditions and, thus, it can create a significant confusion, both for the patient and the therapist, regarding the therapeutic utility of psychotherapy assisted by psychedelics. To this it is added the fact that, until now, there have been no estimates regarding the costs of this therapy(10). On the other hand, Data Bridge Market Research estimates that, during the forecast period 2020-2027, the market for psychedelic drugs in the US is expected to grow to 6859.95 million USD by 2027, from 2077.90 million USD in 2019. Also, for the forecast period 2020-2027, Data Bridge Market Research believes that the European market for psychedelic drugs is expected to grow to 361.13 million USD by 2027(11).

Regarding the population’s acceptance of the use of psychedelics in the treatment of mental disorders, a study that included 3050 adults, living in the USA, Canada, the United Kingdom, France and Germany, highlighted the fact that 65% of respondents agreed or deeply agreed with the statement that they would consider using this treatment option, if it were approved and proposed by the doctor(12,13). Also, in a study conducted in the USA, which included 324 psychiatrists, 42.5% moderately or strongly agreed with the statement that “the use of hallucinogens shows promise in the treatment of psychiatric disorders”. On the other hand, 64.9% moderately or strongly agreed that “the use of hallucinogens increases the risk of subsequent mental disorders”(14).

Regarding the perspectives of the use of psychedelics in the therapy of mental disorders, a controversy persists between scientists and politicians regarding the acceptance of the use of psychedelics. Additionally, their neurobiological and physiological mechanisms of action still require a clear elucidation(12). As in the use of various psychotropic drugs – such as, for example, antidepressants – more rigorous data, based on clinical evidence, are needed before the full acceptance of psychedelics in modern medicine. Also, the education of all interested parties is necessary to reduce the stigma associated with psychedelics, and their use as therapeutic agents will be extremely important for the appropriate clinical use(12,15).

Another important problem regarding the use of psychedelics in therapy is represented by the particularities of informed consent, which must be much more specific compared to that for the usual treatment of a mental disorder. Thus, there are proposals to use phrases that include information about the potential impact of the use of psychedelics in psychotherapy, for example(16,17).

Regarding the possible side effects of the use of psychedelics in the treatment of mental disorders, a meta-analysis that included studies or case reports from the period 1940-2000 indicated rare and transient adverse effects when psychedelics were administered(18). In a study from 1968, Savage et al. highlighted the appearance of transitory psychosis manifestations and a manic reaction(19). Chandler and Hartman, in a study from 1960, reported a case of suicide in a patient with a history of suicide attempts and depressive symptoms, associated with alcohol and drug addiction. The case of a patient who inflicted repeated automutilation injuries and another case of a patient who suffered a “transient psychosis” that lasted until the end of the treatment’s day were also reported(20). The definition of possible adverse events and side effects should constitute a fundamental element of future research in this field(6). However, modern studies regarding the therapeutic use of psychedelics do not indicate the frequent occurrence of worrisome adverse events. The first double-blind, placebo-controlled study that examined the safety and the efficacy of LSD and psilocybin in the treatment of anxiety symptoms associated with terminal illness observed adverse effects such as clinically insignificant elevations in blood pressure, headaches and migraines, nausea, transient anxiety, transient paranoia and transient thought disorders, in the descending order of incidence(21,22).

The studies carried out on patients who were diagnosed with a medical condition in the terminal phase and associated anxiety highlighted the improvement of symptoms, with favorable results that were maintained up to six months after the administration of one or two doses of LSD or psilocybin. Low, repeated doses of LSD can prevent the exacerbation of anxiety symptoms induced by stress, but without affecting other behaviors or depressive symptoms. Repeated doses of LSD have an anxiolytic effect mediated by a mechanism of increasing 5-HT1A neurotransmission and/or by increasing cortical synaptogenesis. But additional studies will be necessary to highlight the therapeutic role of LSD in anxiety disorders which are not associated with medical conditions(23).

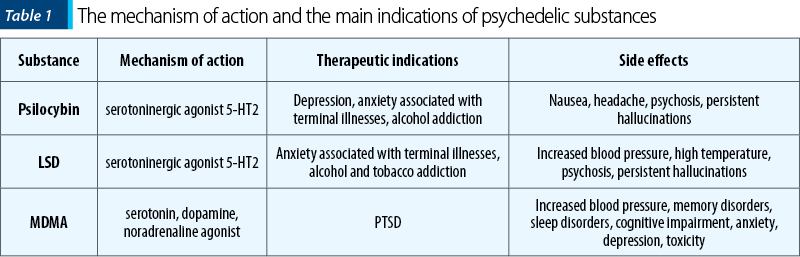

There are still numerous barriers regarding the possibility of studying and the later approval by the competent institutions of the use of psychedelic substances as a therapeutic possibility, taking into account their history of abuse, but also the social prejudices regarding these substances(24). However, in 2018 and later in 2019, the FDA accepted psilocybin to have breakthrough therapy status for the treatment of treatment-resistant depressive disorders or severe depressive disorders. Thus, Table 1 summarizes the possibilities of therapeutic use, as well as the possible side effects of the main psychedelic substances(24).

Psychedelic substances can be used especially in the treatment of those mental disorders that are characterized by the existence of avoidance mechanisms, because these substances can promote the acceptance process. However, there are authors who argue that some avoidance mechanisms may be too strong or inflexible to be resolved with the help of these substances. So, according to the model proposed by Wolff and collaborators, the patient must have a minimum of spontaneous acceptance, otherwise there would be an increased risk of generating experiences without therapeutic value or even worsening the avoidance(25). Therefore, these substances seem to be promising in the treatment of depression, panic disorder, PTSD, psychosomatic disorders or addiction, and they are not recommended in psychotic disorders or ADHD. Also, some authors have supported the use of these substances in the treatment of personality disorders, especially the borderline type(25,26).

In conclusion, in the last 20 years, there has been a revival of clinical and research interest in psychedelic substances. The American Psychiatric Association’s Work Group on Biomarkers and Novel Treatments published in 2020 an extensive study, highlighting the main research on the use of psychedelic substances in the treatment of various mental disorders. If these substances will be approved in the future as a possible therapeutic option, psychiatrists will be directly responsible for their prescription, as well as for the management of these patients. Thus, doctors will have to ensure adequate screening of patients, adequate informed consent, with discussion of possible risks, and the appropriate management of cases of acute medical or psychiatric complications that may occur, including psychomotor agitation or aggressive manifestations. Also, psychiatrists will have to play an important role in providing psychotherapy after the treatment with psychedelics, because there are many patients who will require subsequent therapy sessions to integrate these experiences, lived under the administration of psychedelics, into their daily life, and reduce the possible negative effects persistent after the administration of psychedelics(26,27).

Corresponding author: Ovidiu Alexinschi E-mail: alexinschi@yahoo.com

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: none declared.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: none declared.

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

-

Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, Grant J, Ali A, Gordon L, Ngwa W. Psychedelics. Alternative and Potential Therapeutic Options for Treating Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Molecules. 2022.14;27(8):2520.

-

Wolff M, Evens R, Mertens LJ, Koslowski M, Betzler F, Gründer G, Jungaberle H. Learning to Let Go: A Cognitive-Behavioral Model of How Psychedelic Therapy Promotes Acceptance Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11:5.

-

Roseman L, Nutt DJ, Carhart-Harris RL. Quality of acute psychedelic experience predicts therapeutic efficacy of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Front Pharmacol. 2018;8:974.

-

Carhart-Harris RL, Erritzoe D, Haijen E, Kaelen M, Watts R. Psychedelics and connectedness. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235(2):547–50.

-

Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD; Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs. Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. Lancet. 2010;376(9752):1558-1565.

-

Rucker JJH, Iliff J, Nutt DJ. Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs. Past, present & future. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:200-218.

-

Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, et al. The Therapeutic Potential of Psilocybin. Molecules. 2021;26(10):2948.

-

Dos Santos RG, Osório FL, Crippa JA, Riba J, Zuardi AW, Hallak JE. Antidepressive, anxiolytic, and antiaddictive effects of ayahuasca, psilocybin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD): a systematic review of clinical trials published in the last 25 years. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(3):193-213.

-

Mithoefer MC, Grob CS, Brewerton TD. Novel psychopharmacological therapies for psychiatric disorders: psilocybin and MDMA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(5):481-488.

-

Bahji A, Forsyth A, Groll D, Hawken ER. Efficacy of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020;96:109735.

-

https://www.databridgemarketresearch.com/reports/us-psychedelic-drugs-market

-

Rucker JJ. Evidence versus expectancy: the development of psilocybin therapy. BJ Psych Bull. 2024;48(2):110-117.

-

PSYCH. The Psychedelics as Medicine Report. 4th Ed. PSYCH, 2022. https://psych.global/report/

-

Barnett BS, Siu WO, Pope J, Harrison G. A survey of American psychiatrists’ attitudes toward classic hallucinogens. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206(6):476–80.

-

Fantegrossi WE, Murnane KS, Reissig CJ. The behavioral pharmacology of hallucinogens. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(1):17–33.

-

Smith WR, Appelbaum PS. Novel ethical and policy issues in psychiatric uses of psychedelic substances. Neuropharmacology. 2022;216:109165.

-

https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/233919/depression/rebirth-psychedelic-psychiatry/page/0/3

-

Weston NM, Gibbs D, Bird CIV, et al. Historic psychedelic drug trials and the treatment of anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(12):1261-1279.

-

Savage CC, Hughes MA, Mogar R. The effectiveness of psychedelic (LSD) therapy: A preliminary report. The British Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1968;2(1):59-66.

-

Chandler AL, Hartman MA. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25) as a facilitating agent in psychotherapy. AMA Archives of General Psychiatry. 1960;2(3):286-299.

-

Gasser P, Holstein D, Michel Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(7):513-520.

-

Grob CS, Danforth AL, Chopra GS, et al. Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(1):71-78.

-

De Gregorio D, Inserra A, Enns JP, et al. Repeated lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) reverses stress-induced anxiety-like behavior, cortical synaptogenesis deficits and serotonergic neurotransmission decline. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(6):1188-1198.

-

https://www.clinicaladvisor.com/home/topics/psychiatry-information-center/psychedelics-applications-in-mental-health/

-

Wolff M, Evens R, Mertens LJ, et al. Learning to Let Go: A Cognitive-Behavioral Model of How Psychedelic Therapy Promotes Acceptance. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:5.

-

Zeifman RJ, Wagner AC. Exploring the case for research on incorporating psychedelics within interventions for borderline personality disorder. J Context Behav Sci. 2020;15:1–11.

-

Holoyda B. The rebirth of psychedelic psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):13-16.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Asocierea dintre psihoterapiile structurate şi psihoeducaţie în prevenţia recăderilor din tulburarea bipolară

Tulburările psihice sunt considerate printre cele mai importante probleme de sănătate publică, prin prisma frecvenţei în populaţie şi a costului fo...

Depresia la vârsta a treia – aspecte clinice

Depresia la vârsta a treia, una dintre cele mai frecvente entități nosologice, este deseori subdiagnosticată și subtratată. Diagnosticul precoce și...

„Părinţii mei chiar sunt canibali.“ Schizofrenie paranoidă şi tulburare de personalitate narcisică

Prezentăm cazul unui pacient în vârstă de 35 de ani, diagnosticat cu schizofrenie la vârsta de 22 de ani, cu o personalitate premorbidă dizarmonică...

Managementul sevrajului la alcool

Managementul sevrajului la alcool este unul complex, atât din cauza frecventelor comorbidităţi asociate care trebuie luate în considerare, cât şi a...