Dissociative stupor is a rare psychiatric condition, included in the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) among Other Specified Dissociative Disorders, as an acute dissociative reaction to a stressful event. Like other acute pathological dissociative presentations, it is primarily related to traumatic experiences.

Aim. This article aims at presenting the case of dissociative stupor in a 21-year-old male who presented firstly with mixed symptoms of tonic seizures and catatonia.

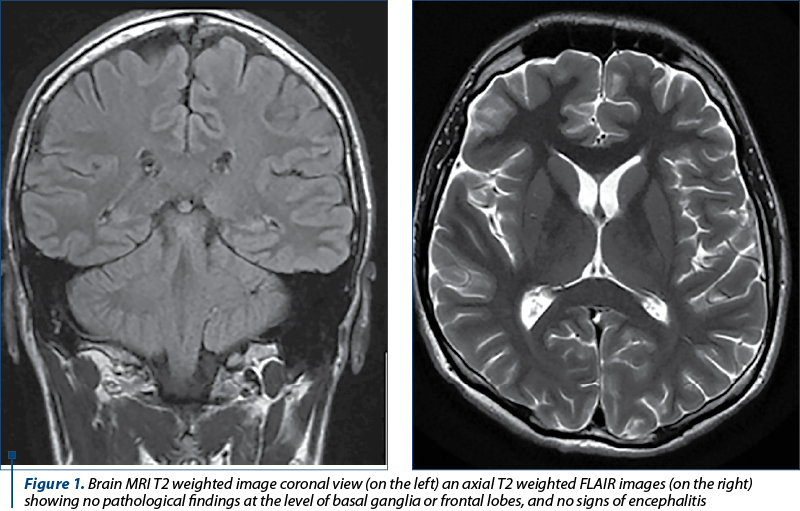

Method. Before the present admission, the patient had two previous emergency department presentations, upon which he presented altered consciousness, muscular rigidity, unresponsiveness to external stimuli, alternated with episodes of psychomotor agitation and visual hallucinations, symptoms partially remitted after the administration of propofol, levetiracetam and solumedrol. During the presentation, the patient’s mother revealed that the patient may have seen the dead body of his grandfather, with whom he had a previously close relationship, and found out in this manner that he passed away during the previous night. Urinary tox-screen was positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Also, complete blood count (CBD), basic metabolic panel (BMP), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), both native and angiographic sequence, and electroencephalogram (EEG) were performed, with results within normal range. The treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI’s; sertraline) and second-generation antipsychotics (SGA; olanzapine) was initiated.

Discussion. From a psychiatric point of view, the patient needs to be reevaluated periodically regarding the psychopharmacologic therapy; also, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or hypnosis may be an option in this case.

Conclusions. The diagnosis and therapeutic management of dissociative stupor represents a real challenge due to the need of excluding other psychiatric or somatic conditions and the fact that there are no available data regarding the psychopharmacological treatment. However, there is much ongoing research in the neurobiology of trauma-related altered states of consciousness and the promising results of them are the basis of future psychopharmacological strategies.

Stuporul disociativ la adultul tânăr. Provocări ale diagnosticului diferenţial şi managementului terapeutic

Dissociative stupor in young adults. Challenges in differential diagnosis and treatment management

First published: 18 aprilie 2022

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.68.1.2022.6310

Abstract

Rezumat

Stuporul disociativ este o afecţiune psihiatrică rară, inclusă în cea de-a cincea ediţie a Manualului de Diagnostic şi Statistică a Tulburărilor Mintale (DSM-5) printre alte tulburări disociative specificate, precum reacţia disociativă acută la un eveniment stresant. Asemănător altor stări disociative patologice acute, este în relaţie directă cu experienţe traumatice.

Scop. Acest articol îşi propune să prezinte un caz de stupor disociativ la un bărbat de 21 de ani care a prezentat în primul rând o simptomatologie mixtă, atât neurologică, de tipul convulsiilor tonice, cât şi psihiatrică, de tipul catatoniei.

Metodă. Anterior internării actuale, pacientul a avut două prezentări la departamentul de primiri urgenţe, cu simptome precum alterarea stării de conştienţă, rigiditate musculară, lipsă de răspuns la stimuli externi, alternând cu episoade de agitaţie psihomotorie şi halucinaţii vizuale, simptome parţial remise după administrarea de propofol, levetiracetam şi solumedrol. În timpul prezentării la unitatea de primiri urgenţe, mama pacientului a dezvăluit că pacientul ar fi văzut cadavrul bunicului său, cu care a avut o relaţie apropiată anterior, şi a aflat astfel că a decedat în noaptea precedentă. Evaluarea toxicologică urinară a fost pozitivă pentru tetrahidrocanabinol (THC). De asemenea, s-au efectuat hemoleucogramă completă, biochimie, analiza lichidului cefalorahidian (LCR), imagistică prin rezonanţă magnetică cerebrală (RMN), atât secvenţa nativă, cât şi angiografică, şi electroencefalogramă (EEG), cu rezultate în limite normale. A fost iniţiat tratament cu inhibitori selectivi de recaptare a serotoninei (ISRS; sertralină) şi antipsihotice de generaţia a doua (olanzapină).

Discuţie. Din punct de vedere psihiatric, pacientul trebuie reevaluat periodic în ceea ce priveşte terapia psihofarmacologică; de asemenea, terapia cognitiv-comportamentală sau hipnoza ar putea fi o opţiune în acest caz.

Concluzii. Diagnosticul şi managementul terapeutic al stuporului disociativ reprezintă o provocare, din cauza nevoii de excludere a altor afecţiuni psihiatrice şi somatice şi a lipsei unui tratament psihofarmacologic specific. Totuşi, există multe cercetări privind neurobiologia tulburărilor conştienţei legate de traumă, iar rezultatele promiţătoare pot reprezenta baza unor viitoare strategii psihofarmacologice.

Introduction

Dissociative stupor is a rare psychiatric condition, included both in the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), among Other Specified Dissociative Disorders, as an acute dissociative reaction to a stressful event, and in the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), among Dissociative (Conversion) Disorders. In modern psychiatry, dissociation is conceptualized as a disruption, interruption or discontinuity of the subjective normal integration of potentially any experience, including behavior, memory, identity, consciousness, emotion, perception, body representation and motor control. Pathological dissociative presentations can occur acutely, primarily related to traumatic and/or overwhelming experiences, or as lifelong dissociative adaptations such as dissociative identity disorder(1). To date, there is little epidemiological data regarding the incidence and prevalence of dissociative stupor in the general population. However, some studies report the prevalence of dissociative disorders in the United States of America as high as 1.5% in the general population, roughly equal across genders: 1.6% for males and 1.4% for females(2). Other studies report higher rates in the general population of dissociative disorders, ranging from 12.2% to 18.3%, with high rates of dissociative amnesia (6-7.3%)(1).

There are few genetic studies regarding dissociative disorders; nevertheless, twin studies comparing monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs suggest that genetic factors may explain 50% or more of the interindividual variance in dissociative symptoms. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes like 5-HTTLPR, relating to serotonin function, have been associated with increased pathological dissociation symptoms. The FKBP5 gene was associated with dissociative symptoms in women with childhood trauma histories, and COMT gene has been linked to increased dissociative symptoms in abused children. There are also genetic data regarding genes involved in one’s trait hypnotizability, and a gene polymorphism relating to dopaminergic function (COMTVal158Met) has been associated with individual differences in hypnotizability(1). To date, there are no available data regarding neurobiology and dissociative stupor; however, there are a few theories applied on animal models as a basis for understanding dissociative responses in the context of traumatic experience. Maggie Schauer and Thomas Elbert have suggested that traumatic events that provoke marked psychobiological arousal may lead to a prolonged immobile defensive posture in humans, similar to the animal defense of “playing dead”. They hypothesize that this leads to functional sensory deafferentation at the level of the thalamus, gating what are otherwise overwhelming incoming visual, auditory, somatosensory and proprioceptive information. This survival-based psychobiological process may compromise sensory integration and modulation at limbic (amygdala, hippocampus) and higher cortical centers (e.g., frontal cortex, anterior cingulate, occipital cortex), that is dissociation at the neurobiological level. These freezing behaviors are commonly reported by individuals experiencing extreme trauma where they cannot fight or flee – for example, rape and/or in situations of captivity. Individuals with severe early life trauma histories with dissociative disorders often report involuntary immobilization and freezing in response to earlier life danger that persists into their later lives.

There are also other ways to induce a dissociative state. Drug use is associated with dissociative symptoms such as depersonalization, derealization and distorted sense of time. Drugs that have been reported to produce these dissociative symptoms include marijuana, hallucinogens, opiates, cocaine and its relatives, and dissociative anesthetics such as ketamine. A series of studies using ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist that increases glutamate release, have suggested that dysregulation of the NMDA glutamate receptor may play a central role in dissociative symptoms. Ketamine produces dose-dependent increases in dissociative symptoms, including the slower perception of time, tunnel vision, derealization and depersonalization. The treatment with a benzodiazepine or with lamotrigine, an anticonvulsant that decreases glutamate release, reduces by about a half the dissociative effects of ketamine. Other neurochemical systems putatively implicated in depersonalization and derealization include the cannabinoid system. Cannabinoids, such as marijuana, have been consistently shown to induce depersonalization, with a pronounced component of temporal disintegration. In addition to their action at the cannabinoid CB receptors, cannabinoids block NMDA receptors at sites distinct from other noncompetitive NMDA antagonists. A PET study using intravenous tetrahydrocannabinol (the active compound in marijuana) found that cerebral blood flow increase in the right frontal and anterior cingulate correlated with depersonalization severity, while there was a subcortical cerebral blood flow decrease in the amygdala, hippocampus, basal ganglia and thalamus(1).

Regarding diagnosis, the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) requires the symptoms of the characteristic dissociative disorder to cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning, without meeting the full criteria of any of the disorders in the dissociative disorders diagnostic class. Furthermore, being a transient condition, it is included as an acute dissociative reaction to a stressful event, lasting typically less than one month, and sometimes only for hours or days(3). According to the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), in order to make a diagnosis of dissociative stupor, one requires to fulfill the criteria for stupor, without any evidence of physical cause, along with positive evidence of psychogenic causation in the form of either recent stressful events or prominent interpersonal or social problems. Stupor is diagnosed on the basis of a profound diminution or absence of voluntary movement and normal responsiveness to external stimuli such as light, noise and touch. The individual lies or sits largely motionless for long periods of time. Speech and spontaneous and purposeful movement are completely or almost completely absent. Although some degree of disturbance of consciousness may be present, muscle tone, posture, breathing and sometimes eye-opening and coordinated eye movements are present, such that it is clear that the individual is neither asleep nor unconscious(4).

Regarding treatment, to date there are no available data regarding treatment options in dissociative stupor, and experts mainly have focused on recommendations of other dissociative disorders such as dissociative identity disorder or amnestic disorder. Guidelines for the use of medications with dissociative patients emphasize the need to identify specific treatment-responsive symptoms rather than attempting to treat the dissociation per se. Medications may be helpful in attenuating symptoms to assist the patient in stabilizing during treatment. As a hypothetical expansion, psychopharmacological strategies adopted in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder or symptoms of dissociative identity disorder may be useful to treat dissociative stupor, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (if the patient can reliably maintain diet safely), mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines, SGA, first-generation antipsychotics (FGA; if the patient fails trials of SGA), β-blockers and selective opioid receptor antagonist(1). Hypnosis is a set of techniques that facilitate treatment, not a treatment in and of itself. It may be useful in identifying the past traumatic experience after the patient’s stuporous state resolves, and later to help create relaxed mental states in which negative life events can be examined without overwhelming anxiety(1).

Case report

In November 2021, a 21-year-old patient was brought to the Neurology Clinic of the Cluj County Emergency Clinical Hospital, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, sent from the Baia Mare Emergency Hospital for waxy flexibility, negativism, posturing, generalized muscular rigidity, and fixity of posture regardless of external stimuli. The current disease began insidiously in August 2021 by altered state of consciousness, tonic crises and behavioral disorder due to alcohol and psychoactive substances intake. The symptoms completely remitted after the administration of propofol, being discharged at home with antiepileptic treatment, levetiracetam 1 g/day, with the patient showing a good evolution, with socioprofessional reintegration. Three months later the patient was hospitalized in the Sighetu-Marmaţiei Municipal Hospital, at the neurology department, for altered state of consciousness and generalized muscular rigidity. Given the altered state of consciousness, a magnetic resonance angiography was performed, with no acute changes described. The patient underwent a lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analyses and the cytological examination revealed: clear liquid appearance, CSF biochemistry with no abnormal cells, but with cytologic-albumin dissociation detected (50.1 mg/dL). the treatment was started with 3 g of solumedrol, with the partial relief of the symptoms, and he was later transferred to our neurological clinic for further investigation.

The neurological examination at admission revealed temporo-spatial disorientation, confusion, no involuntary movements were observed, no cranial nerves involved, without motor deficit, no coordination disturbances, bradylalia and bradypsychia.

The differential diagnosis focused on the exclusion of neurological pathologies such as nonconvulsive status epilepticus, stiff-person syndrome, stroke, anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis, anti-VGKC-complex encephalitis, neuroacanthosis, and Wilson’s disease with psychiatric onset. The routine laboratory findings revealed hepatocytolysis syndrome (GPT-90 U/L, GOT-68 U/L) and mild deficit of B12 vitamin (170 ng/dl). Serum ceruloplasmin level was low (12.94 mg/dL), but serum copper level was within range which ruled out Wilson’s disease. Peripheral blood smear was in normal range, which also made the neuroacanthosis disease excluded. HIV and syphilis screening was negative. PTH was normal which excluded stiff-person syndrome. Serum immunology panel did not reveal any modifications (p-ANCA, c-ANCA, Borrelia IgG + IgM, anti-RO, dc DNA). The EEG was performed in our hospital but did not reveal any ictal discharges or other EEG abnormalities. To rule out autoimmune encephalitis, in particular anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis and anti-VGKC-complex encephalitis, NMDA receptor antibody, IgG and anti-voltage-gated potassium channel antibodies (anti-VGKC-Ab) were harvested from the cerebrospinal fluid, but within normal range.

The lumbar puncture revealed clear liquid appearance, CSF biochemistry with no abnormal cells, but with cytologic-albumin dissociation detected (50.1 mg/dL). To rule out autoimmune encephalitis, in particular anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis and anti-VGKC-complex encephalitis, NMDA receptor antibody, IgG and anti-voltage-gated potassium channel antibodies (anti-VGKC-Ab) were harvested from the cerebrospinal fluid, but within normal range.

One week after the admission, the patient became apathetic, lacking voluntary movements, he did not react to external stimuli, with akinetic mutism, sweating and sinus tachycardia. Given the high suspicion of catatonic syndrome, lorazepam 2 mg (i.v.) was administered, with the relief of clinical symptoms within 15 minutes. Excluding the already aforementioned neurological disorders, a psychiatric consult was performed and the patient was transferred to the psychiatry department. On admission in the psychiatry department, the patient was absent of psychomotor activity, presented both passive and active motor negativism, total verbal negativism, altered conscious state with nonverbal response to pain stimulation, symptoms highly variable in intensity, with episodes of remission during treatment administration and dining.

The patient’s mental status during the remission of negativism had the following characteristics.

Appearance

Personal identification: alternating cooperative with uncooperative episodes, evasive look.

Behavior and psychomotor activity: low levels of psychomotor activity, low interest in motor activity, describing high levels of fatigue and need for bed rest.

General description: partially neat clothing, avoiding eye contact during episodes of remission.

Speech:

Low intensity, monotonous, slightly lacking productivity.

Mood and affect

Mood: low levels of anxiety regarding current admission at the observatory psychiatric ward.

Affect: low level of anxiety expression

Thinking and perception

Form of thinking

Productivity: slow thinking, the patient speaks only when questions are asked.

Continuity of thought: normal continuity

Language impairments: coherent speech.

Content of thinking and thought disturbances: absence of abnormal thought content.

Risk assessment: absence of suicidal or homicidal ideation.

Perceptual disturbances

Hallucinations and illusions: absence of perceptual abnormalities.

Depersonalization and derealization: one episode of depersonalization during the first admission after being death threatened by his cannabis provider.

Sensorium

Alertness: fluctuation in the level of awareness from preserved vigilance to stupor.

Orientation

Time: the patient identifies the year and month correctly but he doesn’t know the exact date.

Place: the patient knows that he is in a psychiatric hospital.

Person: The patient doesn’t know the name but recognizes the appearance of the examiner.

Concentration and calculation: slightly slow mental calculation process.

Memory

Remote memory: the patient recognizes important events that occurred when the patient was younger and free of illness.

Recent past memory: intact memory of the past few months, with selective amnesia regarding his grandfather’s death.

Recent memory: capable to recall what he did the day before.

Immediate retention and recall: unable to repeat all figures after the examiner dictates them, unable to repeat at all backward.

Effect of defect on patient: the patient hasn’t developed coping mechanisms with the defect.

Fund of knowledge: the patient has difficulties functioning at the level of his formal education.

Abstract thinking: low abstraction capability.

Insight: incapable of recognizing the illness.

Judgment: fair social judgment during the psychiatric interview.

The physical examination revealed generalized sweating and body temperature up to 37.8-38ºC. A real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test for the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was performed, with a positive result. The patient underwent full protocol investigation for SARS-CoV-2 infection, with a favorable outcome, establishing an asymptomatic form of the disease, without the need for treatment. Our differential diagnosis at this point included catatonic stupor, depressive stupor, manic stupor and dissociative stupor. Concluding from the clinical presentation and the heteroanamnestic data from the patient’s family, the lack of imagistic and laboratory pathological evidence, we established the diagnosis of dissociative stupor, based on the extremely probable psychotraumatic past situation of the patient finding of his grandfather’s death by seeing his body lying on the bed absent of life. Regarding the past use of cannabis, we considered it an aggravating factor due to the possible dissociation outcome following the cannabinoids ability to block NMDA receptors at sites distinct from other noncompetitive NMDA antagonists. Psychiatric treatment was initialized using up to 6 mg of lorazepam/day, 20 mg of olanzapine and 50 mg of sertraline. Also, during the stupor episodes, the patient received intradermic suggestive therapy injected in the dorsal neck region, with an immediate favorable response. He was discharged after 44 days of hospitalization with a favorable outcome, with recommendations of complete abstinence regarding cannabis, alcohol or any other psychoactive substances, to continue the treatment with olanzapine 10 mg/day and sertraline 50 mg/day, with monthly reevaluation and initiation of CBT in order to achieve the coping mechanisms needed to ease the passing away of his grandfather.

Discussion

This case represented increased challenges due to the heterogeneous clinical manifestation, the high number of neurologic and psychiatric differential diagnostics and the need to exclude every one of them in order to establish the psychogenic etiology. The patient’s current psychiatric status has improved, being now able to engage in social and professional activities.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of dissociative stupor remains a challenge because of the many other differential diagnoses and etiological causes of stupor which require consideration and investigation in order to be excluded. Once established, the severity of the stressor varies, including frankly traumatic events such as the unexpected, violent death of a relative, or experiencing a natural disaster. However, less stressful events may also precipitate this presentation. Although to date there is no available data regarding psychopharmacological treatment options, there is much ongoing research in the neurobiology of trauma-related altered states of consciousness and regarding the neurochemical signaling system in key neurological pathways involved in the pathological process, the promising results of which are the basis of future psychopharmacological strategies.

Bibliografie

-

Sadock B, Sadock V, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017.

-

Tasman A, Kay J, Liberman JA, First BM, Riba MB. Psychiatry, 4th ed. The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015.

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

-

International Classifications of Mental and Behavioral Disorder: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva. World Health Organization. 1992.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Despre rost și depresie.

Scurte consideraţii lingvistico-medicale