Pregnancy-related elements that should be taken into consideration when facing the important chapter of differentiated thyroid cancer in relationship with the moment of diagnosis versus pregnancy involve distinct scenarios: either the confirmation of this thyroid malady was established before pregnancy (hence, the patient already received the multidisciplinary management), during gestation or immediately after birth. While using radioiodine therapy amid gestation is an absolute contraindication, thyroidectomy is rarely indicated (mostly during the second trimester, preferably being postponed after delivery). Here, we aim to introduce the case of an adult female of reproductive age seeking for fertility while she was suspected for a thyroid cancer. She delayed both the thyroid surgery and the pregnancy (despite recommendations) for almost 10 years and, hence, we discuss the practical points that come when dealing with thyroidectomy decision versus the decision to conceive.

Conundrum of differentiated thyroid cancer amid pregnancy

Provocările cancerului tiroidian diferenţiat în sarcină

First published: 22 decembrie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.71.4.2023.9132

Abstract

Rezumat

Elementele legate de sarcină care ar trebui luate în consideraţie privind importantul capitol al cancerului tiroidian diferenţiat în relaţie cu momentul diagnosticului său versus sarcină include scenarii diferite: fie confirmarea afecţiunii tiroidiene a fost stabilită înaintea sarcinii (deci pacienta deja a urmat un management multidisciplinar), în timpul gestaţiei sau imediat după naştere. Aplicarea radioiodoterapiei în timpul sarcinii este o contraindicaţie absolută, în timp ce tiroidectomia este rar indicată (cel mai probabil, în trimestrul al doilea al sarcinii, dar este de preferat să fie amânată după naştere). Ne propunem să introducem cazul unei femei de vârstă reproductivă care doreşte o sarcină, în timp ce investigaţiile au suspicionat un cancer tiroidian. Pacienta a tergiversat chirurgia tiroidiană, dar şi sarcina (în ciuda recomandărilor) pentru aproximativ 10 ani. În acest context, vom discuta aspectele practice care sunt asociate deciziei de tiroidectomie versus deciziei de a concepe.

1. Introduction

Primary thyroid malignancy embraces several types, namely differentiated (papillary and follicular), medullary and anaplastic, the differentiated forms representing the most frequent endocrine cancer(1,2). The medical progress of modern era and the introducing of screening protocols in several high-risk population subgroups, as well as the iodination national programs improved the epidemiologic impact and the outcome; however, this condition remains a current issue with multidisciplinary interplay(3,4).

Pregnancy-related elements that should be taken into consideration when facing the important chapter of thyroid cancer in relationship with the moment of diagnosis versus pregnancy involve distinct scenarios: either the diagnosis of this thyroid malady was established before pregnancy, during gestation, or immediately after birth(5,6).

The impact of prior applied therapies in cases of pre-pregnancy management includes post-thyroidectomy-associated hypothyroidism and the need of lifelong levothyroxine replacement, respectively, the adjustment of the doses during each gestation trimester, and previously (if any) radioiodine therapy that requires a free interval of at least six months up to two years (depending on the dose and guidelines) until conception(7,8). If the confirmation or suspicion of a thyroid malignancy is done for the first time in life when the subject is already pregnant, thyroidectomy should be decided only in a selected number of cases, while “wait and see” approach seems more adequate in most subjects for the concern of mother’s and fetus’s health(9,10). If the diagnosis is performed postpartum, the interferences with the natural process of breastfeeding should be cautiously assessed(11,12).

Of note, the typical acumen of the thyroid neoplasia management involves radioiodine therapy and thyroid/whole body scintigram based on using 123 or 131 iodine tracers that are prohibited amid gestation; also, in certain individuals, the assessment of lymph nodes involvement (such as those from laterocervical area) and even distant metastases (like lung spreading) requires computed tomography which cannot be done under these specific circumstances, thus raising new challenges for the clinicians(13,14). Another important aspect relates to the safety of providing thyroid surgery to a pregnant female, and only a limited time window allows the procedure during the second trimester (or, ideally, after delivery)(14,15).

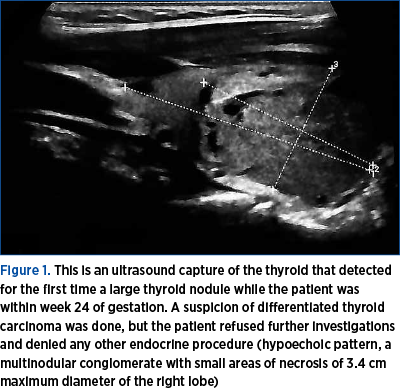

Other essential insight is derivate from the adherence and compliance of a pregnant female to a close follow-up amid the endocrine requirements during pregnancy in these specific instances such as monthly hormonal testing for iatrogenic hypothyroidism and regular thyroglobulin assays or ultrasound surveillance for suspected thyroid nodules with prompt decision of fine needle aspiration or even thyroid removal(16,17). A particular impact of delaying or dismissing supplementary endocrine investigations in gestation was registered during the COVID-19 pandemic due to associated regulations and restrictions(18,19) (Figure 1).

Here, we aim to introduce the case of an adult female of reproductive age seeking for fertility while she was suspected for a thyroid cancer; she delayed both the thyroid surgery and the pregnancy (despite recommendations) for almost 10 years and, hence, we discuss the practical points that come when dealing with thyroidectomy decision versus the decision to conceive.

2. Case presentation

We present the case of a 33-year-old female who was admitted for a thyroid nodule checkup that was previously detected (a decade ago) while she was seeking for her fertility status in order to become pregnant. Currently, the clinical presentation was within normal limits, except for a large, multinodular goiter with no palpable local lymph nodes. Her family medical history included both parents with high blood pressure starting with their seventh decade of life.

Her medical records showed (10 years prior) the identification of a thyroid nodule on the right lobe of 2.8 cm maximum diameter, with normal thyroid function and negative antibodies against thyroid and serum calcitonin. After one year since the initial diagnosis, the nodule increased and a fine needle aspiration was performed; the cytological report showed follicular aspects with some areas of hyperplasia, positive colloid, and a follicular adenoma with areas of hemorrhage and post-hemorrhage resorption (cystic transformation). Within the following two years, the thyroid nodule moderately increased, and two microcalcifications were added to the ultrasound traits (within the nodule and perinodular). Hence, a suspicion of a papillary thyroid carcinoma was done, and thyroidectomy was recommended which the patient delayed, neither had she opted for a pregnancy in the meantime due to thyroid concerns. She remained on ultrasound surveillance and she looked for other second opinions that were all conclusive in the favor of thyroid removal (which the patient continued to refuse).

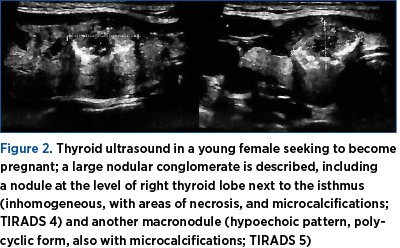

However, during the pandemic years, she was no longer under follow-up for three years until early post-pandemic period when she was admitted once again for intermittent neck compressive symptoms. This current evaluation showed TIRADS4 lesions at ultrasound (Figure 2).

Furthermore, fine needle aspiration was repeated and showed a prior hemorrhagic background with chronic inflammation, frequent follicular epithelium having a compact and trabecular pattern, oxyphil areas, anisocytosis, nuclear inclusions, hyperchromia, and rare psammoma bodies; overall, these highlights were suggestive features for a papillary thyroid carcinoma (Bethesda 6).

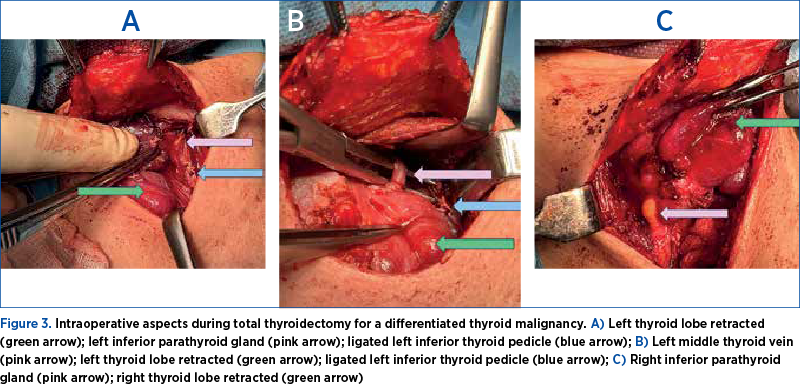

The lady finally agreed to undergo total thyroidectomy which was performed without any complication (Figure 3).

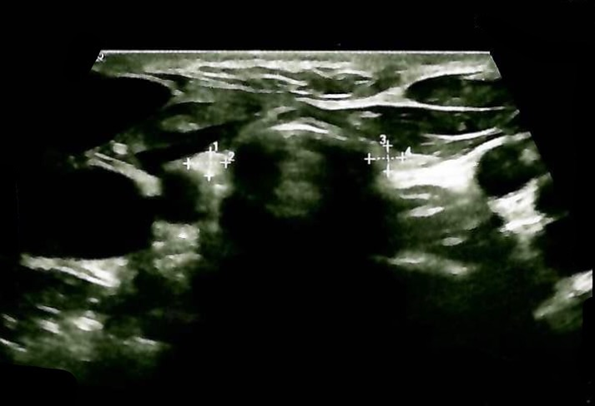

The postoperative period was uneventful, and iatrogenic hypothyroidism required the initiation of replacement therapy followed by TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) suppressive levothyroxine-based therapy (100 µg daily morning and periodic checkup of the thyroid profile) because of the malignancy confirmation. The serum thyroglobulin was 0.04 ng/mL (with negative anti-thyroglobulin antibodies) at TSH of 0.13 µUI/mL (normal values between 0.5 and 4.5 µUI/mL, but targeted TSH due to pathological report is 0.1-0.5 µUI/mL) and a FT4 (free levothyroxine) level of 17.2 pmol/L (normal range between 9 and 19 pmol/L). Early postoperative ultrasound showed no remnants, only a very small edema (Figure 4).

The pathological report confirmed a papillary thyroid carcinoma located at the junction between the right inferior lobe and the isthmus, partially encapsulated, mildly infiltrative to the surroundings, of 1.4 by 1.2 cm, with papillary and follicular pattern, associating frequent psammoma bodies (pT1bpNx LVI+). Further on, the patient is planned for a radioiodine therapy which should delay the conception for at least one year, thyroid malignancy-related features representing a priority at this point in the overall multidisciplinary management. Nevertheless, a future pregnancy will not impact the outcome of the thyroid condition, thus it is not contraindicated (only delayed for medical purposes). Periodic analyses for TSH, free T4, thyroglobulin and thyroid ultrasound are lifelong mandatory.

3. Discussion

This case’ hallmarks are as follows:

Potential pregnancy-related evolution of a differentiated thyroid cancer

Generally, a thyroid nodule detected during pregnancy or during pre-gestation has a low rate of growth when taking into consideration the potential impact of the pregnancy-related environment and hormonal pattern, as well as the fetal development. Overall, there is a reduced risk of malignancy transformation, pregnancy not being regarded as a risk factor for a thyroid nodule/malignancy, neither statistically significantly impacts the prognostic of a previously diagnosed thyroid cancer(20,21). The standard care is similar to non-pregnant subjects to a certain point; however, in cases when fine needle aspiration-based cytological report indicated a differentiated thyroid cancer, the immediate surgical approach is less likely to be recommended until birth, with no particular concern to the maternal and fetal outcomes(22,23). However, as seen in this case, a highly suggestive thyroid nodule for a malignancy should be addressed and managed before conception in order to ensure the best prognosis, both from an endocrine/endocrine surgery and obstetrical perspective(24,25).

Maternal-fetal risks: the thyroid perspective

The current trend of delaying motherhood is in fact applicable for the women who were priorly diagnosed and treated for a papillary and/or follicular thyroid cancer, particularly for those who received radioiodine therapy(26,27). Yet, most meta-analyses agree that the rate of negative outcomes such a premature labor, miscarriage and congenital anomalies is similar to that of women of reproductive age without a history of thyroid cancer(28). Moreover, the presence of a suspected thyroid nodule amid gestation does not represent a fetal risk factor with concern to birth and newborn period(29). When dealing with a woman of reproductive age who is planning a pregnancy (but not in a matter of days or weeks), a thyroid nodule that is very suggestive for being a cancer should be addressed, as in the present case(30).

Maternal post-thyroidectomy hypothyroidism (as in our case) is easily manageable during pregnancy similarly to the group of pregnant females who display hypothyroidism due to other causes such as autoimmune Hashimoto’s thyroiditis that represents the most frequent cause of low thyroid hormones levels in nonendemic areas(23,31). Of course, additional multidisciplinary management should pay attention to the comorbidities of the future mother, as well as syndromic endocrine conditions etc.(32-34) Untreated hypothyroidism might bring additional risks with cardiovascular and metabolic impact on one hand, while overtreatment with levothyroxine might increase the cardiac rhythms, systolic blood pressure and even bone resorption(23,35).

Patient’s compliance

This was a real-life-medicine situation whereas the lady delayed undergoing thyroidectomy for almost a decade during her reproductive years. The importance of patient’s education is essential for a better outcome. Consecutively, the subject should adhere to the surveillance plan that includes periodical hormonal check-up in addition to tumor markers assays; during pregnancy, an increase of levothyroxine doses is expected to be offered to the subjects(36,37). In case of cancer relapse, radioiodine therapy or, alternatively, redo surgery should be taken into consideration but, if this happens during pregnancy, ideally, surgery should be postponed after delivery, while radioiodine is strictly contraindicated during gestation(38,39).

4. Conclusions

Despite prior opinions that pregnancy represents a risk factor for a differentiated thyroid cancer, this aspect is mostly no longer available nowadays. However, a particular awareness is required in a selected high-risk subgroup of patients confirmed (as in this case) with a more aggressive form following thyroidectomy and requiring an adequate radioiodine therapy that should delay the conception. A multidisciplinary team is mandatory.

Acknowledgement. We thank the medical and surgical teams that were involved in the case and patient’s surveillance over the years. We thank the patient for her written consent upon agreeing to present her medical records. The Ethical approval to introduce the thyroid parameters (no. 608/28.06.2023) was signed by the Local Ethical Committee of the “Dr. Carol Davila” Central Military Emergency University Hospital, Bucharest, Romania.

Corresponding author: Florica Şandru, e-mail: florysandru@yahoo.com

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

-

Langdon J, Gupta A, Sharbidre K, Czeyda-Pommersheim F, Revzin M. Thyroid cancer in pregnancy: diagnosis, management, and treatment. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2023;48(5):1724-1739.

-

van Velsen EFS, Leung AM, Korevaar TIM. Diagnostic and Treatment Considerations for Thyroid Cancer in Women of Reproductive Age and the Perinatal Period. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2022;51(2):403-416.

-

Tsakiridis I, Giouleka S, Kourtis A, Mamopoulos A, Athanasiadis A, Dagklis T. Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy: A Descriptive Review of Guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2022;77(1):45-62.

-

Lee SY, Pearce EN. Assessment and treatment of thyroid disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18(3):158-171.

-

Haymart MR. Year in Thyroidology - Recent Developments and Future Challenges: Clinical Science Review. Thyroid. 2022;32(1):9-13.

-

Iijima S. Effects of fetal involvement of inadvertent radioactive iodine therapy for the treatment of thyroid diseases during an unsuspected pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;259:53-59.

-

Kitahara CM, Slettebø Daltveit D, Ekbom A, Engeland A, Gissler M, Glimelius I, Grotmol T, Trolle Lagerros Y, Madanat-Harjuoja L, Männistö T, Sørensen HT, Troisi R, Bjørge T. Maternal Health, Pregnancy and Offspring Factors, and Maternal Thyroid Cancer Risk: A Nordic Population-Based Registry Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2023;192(1):70-83.

-

Sorrenti S, Baldini E, Pironi D, Lauro A, D’Orazi V, Tartaglia F, Tripodi D, Lori E, Gagliardi F, Praticò M, Illuminati G, D’Andrea V, Palumbo P, Ulisse S. Iodine: Its Role in Thyroid Hormone Biosynthesis and Beyond. Nutrients. 2021;13(12):4469.

-

Girardelli S, Mangili G, Cosio S, Rabaiotti E, Fanucchi A, Valsecchi L, Candiani M, Gadducci A. A narrative review of pregnancy after malignancies in young women that don’t originate in the female genital organs or in the breast. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;159:103240.

-

Kim HO, Lee K, Lee SM, Seo GH. Association Between Pregnancy Outcomes and Radioactive Iodine Treatment After Thyroidectomy Among Women with Thyroid Cancer. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):54-61.

-

Mannathazhathu AS, George PS, Sudhakaran S, Vasudevan D, Krishna Km J, Booth C, Mathew A. Reproductive factors and thyroid cancer risk: Meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2019;41(12):4199-4208.

-

Peng CC, Pearce EN. An update on thyroid disorders in the postpartum period. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45(8):1497-1506.

-

Colombo C, De Leo S, Giancola N, Trevisan M, Ceruti D, Frattini F, Persani L, Fugazzola L. Persistent Thyroid Carcinoma and Pregnancy: Outcomes in an Italian Series and Review of the Literature. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(22):5515.

-

Winder M, Kosztyła Z, Boral A, Kocełak P, Chudek J. The Impact of Iodine Concentration Disorders on Health and Cancer. Nutrients. 2022;14(11):2209.

-

Horgan D, Führer-Sakel D, Soares P, Alvarez CV, Fugazzola L, Netea-Maier RT, Jarzab B, Kozaric M, Bartes B, Schuster-Bruce J, Dal Maso L, Schlumberger M, Pacini F. Tackling Thyroid Cancer in Europe-The Challenges and Opportunities. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(9):1621.

-

Cao Q, Zhu H, Zhang J, Li Y, Huang W. Pregnancy Outcomes in Thyroid Cancer Survivors: A Propensity Score-Matched Cohort Study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:816132.

-

Jiskra J, Horáček J, Špitálníková S, Paleček J, Límanová Z, Krátký J, Springer D, Žabková K, Vítková H. Thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer in women with positive thyroid screening in pregnancy: a double-centric, retrospective, cohort study. Eur Thyroid J. 2022;11(2):e210011.

-

Popescu M, Ghemigian A, Vasile CM, Costache A, Cârşote M, Ghenea AE. The new entity of subacute thyroiditis amid the COVID-19 pandemic: from infection to vaccine. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022:12(4):960.

-

Şandru F, Cârşote M, Petca RC, Gheorghisan-Gălăţeanu AA, Petca A, Valea A, Dumitraşcu MC. COVID-19-related thyroid conditions (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22(1):276.

-

Angell TE, Alexander EK. Thyroid Nodules and Thyroid Cancer in the Pregnant Woman. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2019;48(3):557-567.

-

Galofré JC, Riesco-Eizaguirre G, Alvarez-Escolá C; Grupo de Trabajo de Cáncer de Tiroides de la Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición. Clinical guidelines for management of thyroid nodule and cancer during pregnancy. Endocrinol Nutr. 2014;61(3):130-8.

-

Papini E, Crescenzi A, D’Amore A, Deandrea M, De Benedictis A, Frasoldati A, Garberoglio R, Guglielmi R, Pio Lombardi C, Mauri G, Elisa Miceli R, Puglisi S, Rago T, Salvatore D, Triggiani V, Van Doorne D, Mitrova Z, Saulle R, Vecchi S, Basile M, Scoppola A, Paoletta A, Persichetti A, Samperi I, Cozzi R, Grimaldi F, Boniardi M, Camaioni A, Elisei R, Guastamacchia E, Nati G, Novo T, Salvatori M, Spiezia S, Vallone G, Zini M, Attanasio R. Italian Guidelines for the Management of Non-Functioning Benign and Locally Symptomatic Thyroid Nodules. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2023;23(6):876-885.

-

Li LQ, Hilmi O, England J, Tolley N. An update on the management of thyroid nodules: rationalising the guidelines. J Laryngol Otol. 2023;137(9):965-970.

-

Yamazaki H, Sugino K, Noh JY, Katoh R, Matsuzu K, Masaki C, Akaishi J, Hames KY, Tomoda C, Suzuki A, Ohkuwa K, Kitagawa W, Nagahama M, Rino Y, Ito K. Clinical course and outcome of differentiated thyroid cancer patients with pregnancy after diagnosis of distant metastasis. Endocrine. 2022;76(1):78-84.

-

Stagnaro-Green A. Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy: A Touch of Clarity. Thyroid. 2022;32(4):347-348.

-

Toro-Wills MF, Imitola-Madero A, Alvarez-Londoño A, Hernández-Blanquisett A, Martínez-Ávila MC. Thyroid cancer in women of reproductive age: Key issues for the clinical team. Women’s Health (Lond). 2022;18:17455057221136392.

-

Ding Z, Guo F, Zhou Y, Huang X, Liu Z, Fan J. Thyroxine Supplementation in Pregnant Women After Thyroidectomy for Thyroid Cancer and Neonatal Birth Weight. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:728199.

-

Moon S, Yi KH, Park YJ. Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Young Women with Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(10):2382.

-

Nobre GM, Tramontin MY, Treistman N, Alves PA Junior, Andrade FA, Bulzico DA, Corbo R, Vaisman F. Pregnancy has no significant impact on the prognosis of differentiated thyroid cancer. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Nov 24;65(6):768-777.

-

Minakata M, Ito M, Kishi T, Hada M, Masaki Y, Nakamura T, Kousaka K, Kasahara T, Kudo T, Nishihara E, Fukata S, Nishikawa M, Akamizu T, Miyauchi A. The magnitude of increased Levothyroxine dose during pregnancy in patients on thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) suppression treatment after total thyroidectomy for papillary carcinoma. Endocr J. 2022;69(2):165-172.

-

Şandru F, Cârşote M, Albu SE, Dumitraşcu MC, Valea A. Vitiligo and chronic autoimmune thyroiditis. J Med Life. 2021;14(2):1-4.

-

Şandru F, Petca A, Dumitraşcu MC, Petca RC, Cârşote M. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: skin manifestations and endocrine anomalies (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2021:22(6):1387.

-

Dumitraşcu MC, Şandru F, Cârşote M, Petca RC, Gheorghisan-Gălăţeanu AA, Petca A, Valea A. Anorexia nervosa: COVID-19 pandemic period (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22(2):804.

-

Radu L, Cârşote M, Gheorghisan-Gălăţeanu AA, Preda SA, Calborean V, Stănescu R, Gheorman V, Albulescu DM. Blood Parathyrin and Mineral Metabolism Dynamics. A clinical analyzes. Rev Chim. 2018;69(10):2754-8.

-

Urgatz B, Poppe KG. Update on therapeutic use of levothyroxine for the management of hypothyroidism during pregnancy. Endocr Connect. 2024:EC-23-0420.

-

Hepp Z, Lage MJ, Espaillat R, Gossain VV. The association between adherence to levothyroxine and economic and clinical outcomes in patients with hypothyroidism in the US. J Med Econ. 2018;21(9):912-919.

-

Biondi B, Wartofsky L. Treatment with thyroid hormone. Endocr Rev. 2014;35(3):433-512.

-

Delshad H, Amouzegar A, Mehran L, Azizi F. Comparison of two guidelines on management of thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer during pregnancy. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(10):670-3.

-

Varghese SS, Varghese A, Ayshford C. Differentiated thyroid cancer and pregnancy. Indian J Surg. 2014;76(4):293-6.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

What do we know about imaging in pregnancy?

Many conditions in pregnancy require noninvasive paraclinical examinations. These kinds of tests should never replace a good clinical examination, ...

Validarea unui sistem de inteligenţă artificială pentru interpretarea traseului antepartum al ritmului cardiac fetal (Ankara System Version 5.0)

The validation of an artificial intelligent system (AIS) – Ankara System Version 5.0 – for the interpretation of antepartum fetal heart rate (FHR) ...

The importance of chronic endometritis and dysbiosis in implantation failure in IVF cycles

We often face in vitro fertilization cycles in which embryo implantation does not occur despite the apparent exclusion of other maternal unfavorabl...

Teenage pregnancy – an unsolved problem of the 21st century. Populational register-based study in the County Clinical Hospital Constanţa

Studies regarding pregnant teenagers were carried out at the beginning of the 1950s, attracting the attention of both the medical community and var...