Introduction. Placenta praevia (PP) is an obstetrical complication where the maturing placenta obstructs a part or all of the internal cervical os. Abnormal placenta invasion and development are associated with a spectrum of conditions rather than a single obstetric pathology. Objective. To review the ultrasound markers for placenta praevia in our experience and correlate the imagistic and histopathological findings. Methodology. This is a retrospective study including 259 patients admitted with the diagnosis of PP in the Obstetrics-Gynecology Clinic II of the County Emergency Clinical Hospital Craiova, Romania, between 2018 and 2023. Results. The most important ultrasound features associated with placenta praevia with accreta were loss of retroplacental hypoechoic area, presence of placental lacunae, presence of bladder wall discontinuity, placental bulge, exophytic mass, subplacental and/or uterovesical hypervascularity, placental lacunae feeder vessels, and bridging vessels. According to the degree of placental invasiveness, the histopathological evaluation showed disorganization of the uterine wall, myocytes anarchically distributed among the villi and decidual cells, neoformation vessels invading the myometrium, and these aspects were correlated with hyperadherence and significant antepartum and intrapartum bleeding. Conclusions. The aforementioned ultrasound features may put doctors on alert and, thus, dictate the appropriate therapeutic management to prevent complications that could endanger fetal or maternal life.

Placenta praevia associated with accreta – update on clinical, imaging and histopathological aspects

Placenta praevia asociată cu accreta – actualizare privind aspectele clinice, imagistice şi histopatologice

First published: 22 decembrie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.71.4.2023.9127

Abstract

Rezumat

Introducere. Placenta praevia (PP) este o complicaţie obstetricală în care placenta în curs de maturizare obstrucţionează parţial sau total orificiul cervical intern. Invazia şi dezvoltarea anormală a placentei asociază un spectru de afecţiuni mai degrabă, decât o singură patologie obstetricală. Obiective. Revizuirea markerilor ecografici pentru placenta praevia în experienţa noastră şi corelarea rezultatelor imagistice şi histopatologice. Metodologie. Acesta este un studiu retrospectiv care a inclus 259 de paciente internate cu diagnosticul de PP în Clinica de obstetrică-ginecologie II a Spitalului Clinic Judeţean de Urgenţă din Craiova, România, în perioada 2018-2023. Rezultate. Cele mai importante caracteristici ecografice asociate cu placenta praevia cu acretizare au fost pierderea zonei hipoecogene retroplacentare, prezenţa lacunelor placentare, prezenţa discontinuităţii peretelui vezicii urinare, impresiune placentară, masă exofitică, hipervascularizaţie subplacentară şi/sau uterovezicală, lacune placentare, vase de alimentare şi vase de legătură. După gradul de invazivitate placentară, din punct de vedere histopatologic, peretele uterin poate fi dezorganizat, miocitele distribuite anarhic între vilozităţile placentare şi celulele deciduale, vasele de neoformaţie invadează miometrul, iar aceste aspecte conduc la hiperaderenţă şi la hemoragii importante antepartum şi intrapartum. Concluzii. Caracteristicile ecografice menţionate anterior pot pune în alertă medicul şi, astfel, să dicteze managementul terapeutic, pentru a preveni complicaţiile care ar putea pune în pericol viaţa fetală sau maternă.

Introduction

Placenta praevia (PP) is an obstetrical complication where the maturing placenta obstructs a part or all of the internal cervical os. It has a prevalence of 5.2 per 1000 pregnancies(1,2). PP can lead to serious maternal and fetal complications as a major cause of antepartum hemorrhage, especially in the third trimester(2). Pregnancies involving placenta praevia also lead to higher frequencies of preterm birth and fetal and neonatal disorders(3-6).

The invasion and abnormal placental development phenomena represent a spectrum of conditions rather than a single obstetric pathology. Each placenta has different degrees of invasion, and the areas affected vary widely from case to case. PP may be associated with abnormal placental implantation and invasion into the myometrium, and it may raise particular surgical challenges, leading to partial or total hysterectomy(7, 8).

The pathogenesis of the disease is not clearly understood(9). The wide variation in the prevalence rate can be attributed to the different degrees of PP, different methods and times for diagnosis, and to the diversity of the patient population studied(9).

Placenta praevia is strongly associated with placenta accreta (PA)(10). The incidence of PA is up to 67% in patients with PP and a history of multiple caesarean section (CS) deliveries(11). This association between CS, PP and PA is becoming increasingly acknowledged. It causes concern, because it implies a significant risk of emergency hysterectomy, with associated negative consequences, increased morbidity and mortality. Morbidities associated with PP include antepartum bleeding requiring blood transfusion, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), abnormal placental adhesion, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)(12), postpartum hemorrhage, sepsis and thrombophlebitis(13). A correct clinical and sonographic diagnosis is crucial for correctly managing PP tasks and for appropriate birth management.

The histopathological examination of morbidly adherent placentas that invade the myometrial structure, correlated with the associated risk factors and clinical and sonographic aspects offers details on the arrangement of placental and myometrial vascularity and outlines the pathogenic mechanisms that led to the development of PP(14).

Several clinical and epidemiological studies have observed an increased incidence of placenta praevia among women with advanced maternal age, multiparity, pregnancy with male fetuses, multiple pregnancies, previous caesarean birth and previous miscarriage or induced abortion. In addition, behavioral factors that have been implicated in the increased occurrence of PP include smoking during pregnancy. Also, pregnant women with a history of PP in a previous pregnancy have a higher risk of developing the condition in a subsequent pregnancy(3-6).

In the United States of America, maternal mortality is estimated at 0.03% of PP cases(13). Pregnant women with placenta praevia can also express significant emotional distress due to recurrent bleeding, along with hospitalizations that often occur in the second half of pregnancy. Placenta praevia is also associated with an increase in preterm birth and perinatal mortality and morbidity. Finally, there is a higher rate of congenital malformations among women with PP, although the specific mechanisms underlying this aspect are unclear(13).

Despite early diagnosis and close surveillance of women with PP, along with great advances in neonatal care, it is still a challenging task to avoid fetal and maternal complications and improve perinatal outcomes among women with this condition(14).

Our study aims to evaluate clinically and sonographically pregnant women with PP and their associated risk factors. We also analyzed the patients’ hemoglobin values and age concerning the clinical presentation, and we studied the histopathological aspects accompanying this condition according to the type of surgery performed.

Materials and method

This is a retrospective study including 259 patients admitted with the diagnosis of placenta praevia in the Obstetrics-Gynecology Clinic II of the County Emergency Clinical Hospital Craiova, Romania, between 2018 and 2023.

The patients were divided into two main groups: PP with bleeding (PP-H) and PP without bleeding (PP-0). Each group was subdivided into three classes: central PP (PP-C), partial PP (PP-P), and marginal PP (PP-M). Also, each class was subdivided according to invasion of the uterine wall into acute PP (PP-a), PP increta (PP-i), and PP percreta (PP-p).

For each class, we took into account the mean hemoglobin (Hb) value, age of the patients, number of previous births, type of previous births, number of previous abortions, smoking status, type of intervention performed for the birth associated with PP, and the histopathological analysis of the invasion into the uterine wall, a comparative analysis being performed using Microsoft Excel.

Transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound scans were performed on each patient using two-dimensional (2D) and color Doppler grayscale, revealing the loss of retroplacental hypoechoic area, the presence of placental lacunae, the presence of bladder wall discontinuity, placental bulge, exophytic mass, subplacental and/or uterovesical hypervascularity, placental lacunae feeder vessels, and bridging vessels. The examinations were performed using ultrasonography (US) machines equipped with 3-5 MHz transabdominal and 3-9 MHz transvaginal linear transducers (Voluson E10). Postoperatively, tissue was harvested from hysterectomy cases for classical histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation. These fragments were submitted to the Center for Microscopic Morphology and Immunology Studies of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Craiova for paraffin embedding, sectioning, staining and analysis. Placental fragments were fixed using 10% formalin at room temperature. Each patient signed the consent in the observation sheet and agreed to participate in this study.

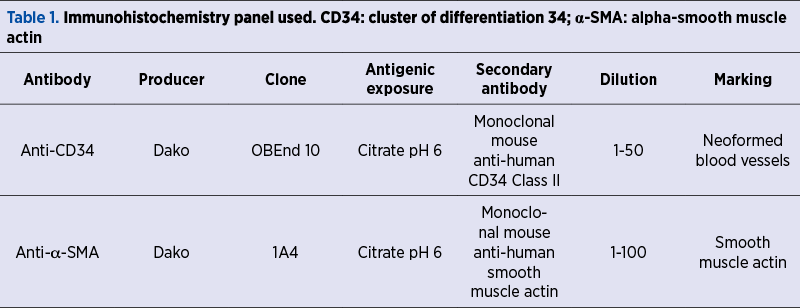

For the microscopic study, we used classical hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. For the immunohistochemical (IHC) study, we used anti-cluster of differentiation 34 (CD34) antibodies to label vascular endothelium alpha-smooth muscle actin (a-SMA) to highlight smooth muscle actin (Table 1).

Results

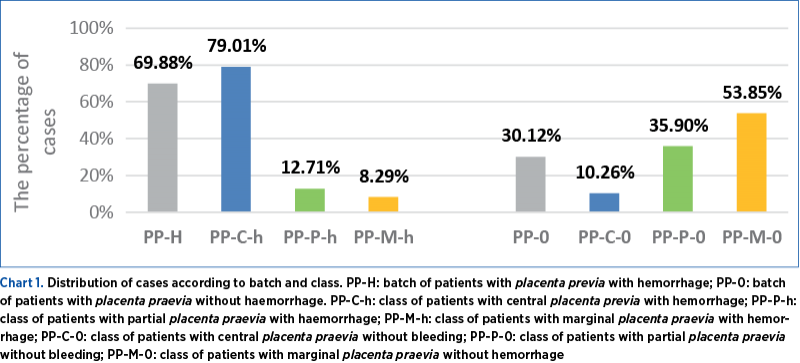

Regarding the distribution by groups, we observed that 69.88% of the patients were enrolled in the PP-H group, and 30.12% were in the PP-0 group. Within the first group, PP-H, 79.01% of the patients were included in the PP-C-h class after ultrasound examination in the third trimester of pregnancy, 12.71% in the PP-P-h class, and 8.29% in the PP-M-h class. In the second group of PP-0 patients, 10.26% were included in the PP-C class, 35.9% in the PP-P class, and 53.85% in the PP-M class (Chart 1 – Distribution of cases according to batch and class).

In the category of patients with PP-C-h, in 81.12% of the cases, caesarean section (CS) was performed, and the placenta was delivered without difficulty. In comparison, in 11.89% of the cases, the placenta could not be delivered during CS, and a total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy was necessary. The hysterectomy specimen was sent for histopathological examination, and the microscopic examination showed that, of the 17 patients presenting with PP-C-h, 88.24% presented with PP-C-a, 5.88% presented with PP-C-i, and 5.88% had PP-C-p. Of the patients with PP-P-h, 86.96% were associated with CS and normal placental abruption, and 13.04% were associated with peripartum total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy. Upon histopathological examination, we observed that all cases were associated with PP-P-a.

In patients with PP-M-h, 93.33% were associated with CS and normal placental abruption, and 6.67% were associated with peripartum total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy. All these patients, following histopathological examination, were diagnosed with PP-M-a. Regarding the group of patients with PP without bleeding, all cases ended with CS and normal intraoperative placental abruption.

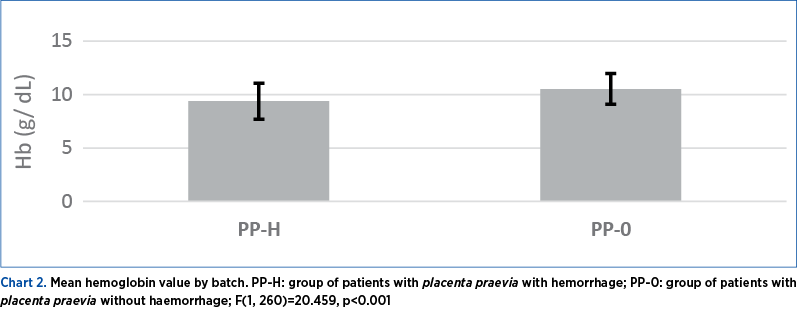

For both groups of patients, the mean pre-birth value of Hb was calculated, and we observed that in the case of PP-H, Hb varied between 7 g/dL and 12.9 g/dL, with a mean value of 9.39 g/dL (±1.69 g/dL), and in the case of PP-0, Hb varied between 8 g/dL and 14.12 g/dL, with a mean value of 10.54 g/dL (±1.44 g/dL) (Chart 2 – Mean hemoglobin value by batch). Using the Anova single factor test, we found statistically significant differences between the two groups – F(1, 260)=20.459; p<0.001.

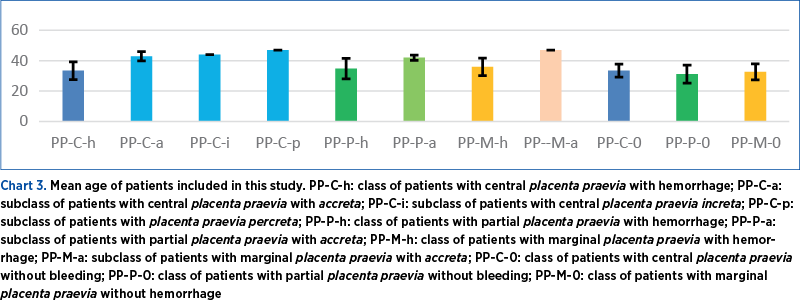

Regarding the age of the patients, we noted that, in the class of patients with PP-C-h, the age ranged from 17 to 49 years old, with a mean value of 33.38 years old (±5.85). Among them, in the case of patients with PP-C-a, the age ranged from 40 to 49 years old, with a mean value of 42.94 years old (±3.07). In the case of patients with PP-C-i, the age was 44 years old, and in the case of patients with PP-C-p, the age was 47 years old. Comparing the mean values, we observe that the highest recorded age was in the case of the PP-C-i patient. As for the PP-P-h patients, the age ranged from 20 to 44 years old, with a mean value of 34.78 years old (±6.7), and in the case of the PP-P-a subclass, the mean age of the three patients was 42 years old (±1.73). In the case of patients with PP-M-h, the age ranged from 24 to 47 years old, with a mean value of 36 years old (±5.76), and the age of the patient with PP-M-a was 47 years old. In the case of patients with PP without bleeding, we observed that in the PP-C-0 class, the age ranged from 24 to 39 years old, with a mean value equal to 33.5 years old (±4.3). In the class of patients with PP-P-0, the age varied between 20 and 43 years old, with a mean value of 31.21 years old (±5.87), and in the case of patients with PP-M-0, the age varied between 22 and 42 years old, with a mean value of 32.64 years old (±5.23). Comparing the two groups of patients, we observe that the age did not fluctuate much. Still, comparing the age of the patients who presented PP-C-a, PP-C-i or PP-C-p, we observe a significant difference of about 10 years (Chart 3 – Mean age of patients included in this study).

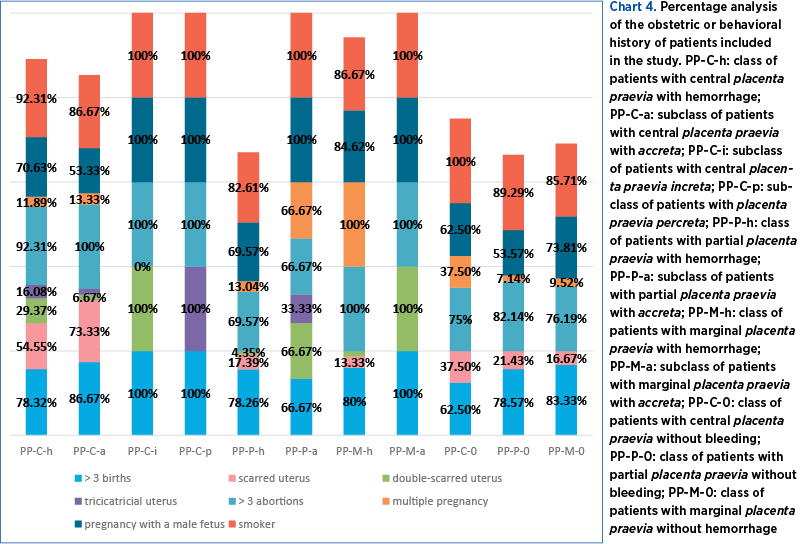

Most of the patients included in the study were multiparous (more than three previous births) and were distributed as follows: 78.32% of the PP-C-h class and 86.67% of the PP-C-a subclass were multiparous, along with 100% of PP-C-i and 100% of PP-C-p, 78.26% of PP-P-h, 66.67% of PP-P-a, 80% of PP-M-h, 100% of PP-M-a, 62.50% of PP-C-0, 78.57% of PP-P-0 and 83.33% of PP-M-0. We thus observe that more than 60% of patients in each class or subclass were multiparous (Chart 4 – Percentage analysis of the obstetric or behavioral history of patients included in the study).

Analyzing the obstetric history of the patients, we observed that 54.55% of PP-C-h, 73.33% of PP-C-a, 17.39% of PP-P-h, 13.33% of PP-M-h, 37.5% of PP-C-0, 21.43% of PP-P-0 and 16.67% of PP-M-0 were associated with a CS birth (Chart 4). Thus, we observe that most PP-C-h or PP-C-0 were associated with previous caesarean section delivery.

Regarding the presence of two caesarean sections in the antecedents, we observed that 29.37% of cases with PP-C-h, 6.67% of PP-C-a, 100% of cases with PP-C-i, 4.35% of cases with PP-P-h, 66.67% of cases with PP-P-a, 6.67% of cases with PP-M-h and 100% of cases with PP-M-a were associated with PP (Chart 4). We thus observe that double scar uterus was most frequently associated with the presence of PP-C-i and PP-M-a.

In cases with a history of three caesarean sections, we observed that 16.08% of PP-C-h, 6.67% of PP-C-a, 100% of PP-C-p, and 33.33% of PP-P-a were associated with PP (Chart 4). Thus, the invasiveness increased according to the number of caesarean deliveries. Regarding the cases with three previous miscarriages, we calculated that 92.31% of PP-C-h, 100% of PP-C-a, 100% of PP-C-i, 100% of PP-C-p, 69.57% of PP-P-h, 66.67% of PP-P-a, 100% of PP-M-h, 100% of PP-M-a, 75% of PP-C-0, 82.14% of PP-P-0, and 76.19% of PP-M-0 were associated with the presence of placenta praevia (Chart 4). We thus note that the percentage of cases with PP increases significantly with the number of previous abortions.

Regarding the association of multiple pregnancies, we found that 11.89% of PP-C-h, 13.33% of PP-C-a, 13.04% of PP-P-h, 66.67% of PP-P-a, 100% of PP-M-h, 37.5% of PP-C-0, 7.14% of PP-P-0 and 9.52% of PP-M-0 had twin pregnancies associated with PP (Chart 4). Thus, we notice that the presence of twin pregnancy can be associated with the presence of PP.

Analyzing the association of pregnancies with PP and the presence of male fetuses, we found that 70.63% of PP-C-h, 53.33% of PP-C-a, 100% of PP-C-i, 100% of PP-C-p, 69.57% of PP-P-h, 100% of PP-P-a, 84.62% of PP-M-h, 100% of PP-M-a, 62.50% of PP-C-0, 53.57% of PP-P-0 and 85.71% of PP-M-0 were associated with male fetuses (Chart 4). Thus, we observe that all classes or subclasses of patients were associated with more than 50% of male fetus pregnancies.

Analyzing patients’ behaviors and association with smoking before and during pregnancy, we observed that 92.31% of PP-C-h, 86.67% of PP-C-a, 100% of PP-C-i, 100% of PP-C-p, 82.61% of PP-P-h, 100% of PP-P-a, 86.67% of PP-M-h, 100% of PP-M-a, 100% of PP-C-0, 89.29% of PP-P-0 and 85.71% of PP-M-0 reported tobacco use before pregnancy and during pregnancy (Chart 4). Therefore, more than 80% of patients in each class and subclass were tobacco users.

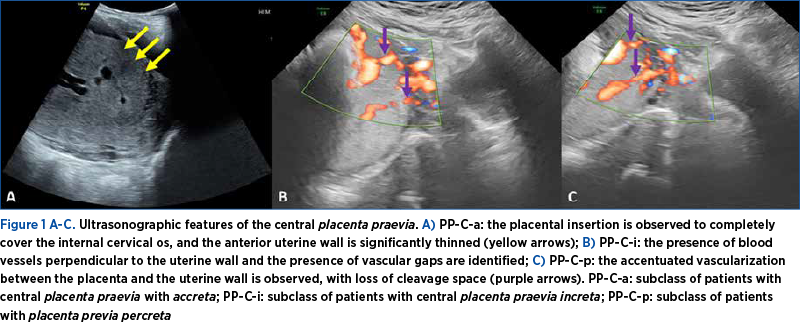

From the sonographic point of view, in cases with PP-C-a, PP-C-i or PP-C-p, we noted the presence of the placenta inserted at the level of the anterior uterine wall, completely covering the internal cervical orifice, passing towards the posterior uterine wall, the presence of multiple, irregular placental lacunae, accompanied by arterial or mixed blood flows, especially with perpendicular arrangement on the uterine wall (Figure 1A-C. Ultrasonographic features of the central placenta praevia). Also, in cases with PP-P-a and PP-M-a, the same sonographic features were observed, except that, in PP-P, the placenta no longer completely covered the internal cervical os, and in PP-M, the placenta was inserted to within 2 cm of the internal cervical os.

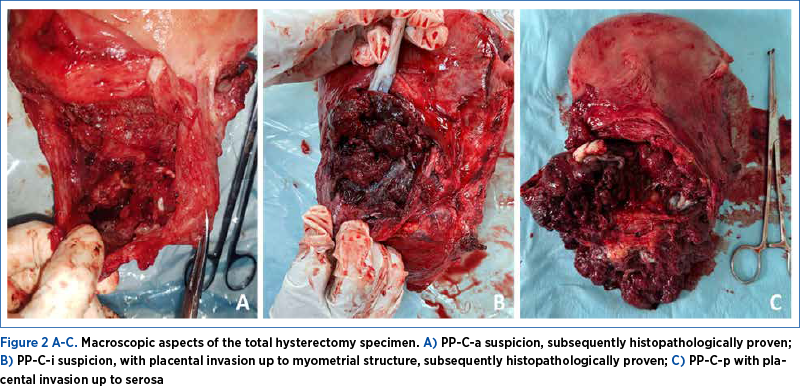

Intraoperatively, in the patients suspected by ultrasound and confirmed intraoperatively with PP-C-a, PP-C-i, PP-C-p or PP-P-a or PP-M-a, in whom the placenta could not be detached manually, emergency hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy was performed. The uterine specimen was sent for histopathological examination and, thus, the diagnosis of invasiveness was made. In these cases, the placental invasion was detected in the uterine wall, up to the level of the uterine serosa. In the case of PP-C-p, an intraoperative cystorrhaphy was required (Figure 2A-C. Macroscopic aspects of the entire hysterectomy specimen).

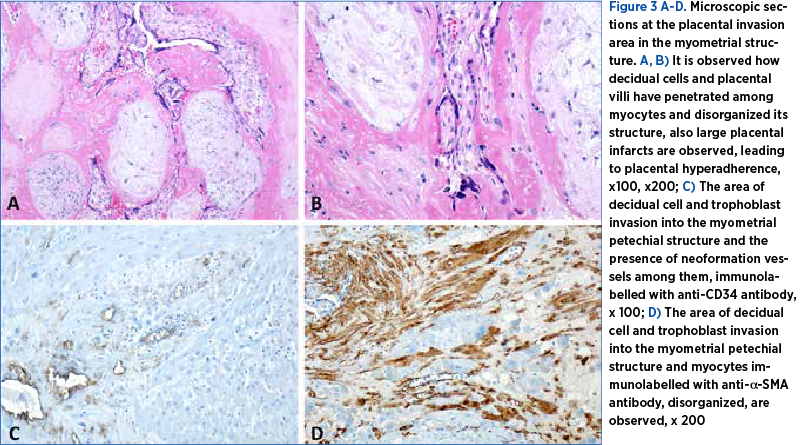

In patients who underwent hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, tissue fragments, including placenta adherent to the uterine wall, were analyzed. Using classical HE staining, we observed that decidual cells and placental villi were present among the myocytes, disorganizing the muscle structure and thus increasing the adhesiveness of the placenta to the uterine wall, making placental detachment impossible (Figure 3A, B. Microscopic sections at the placental invasion area in the myometrial structure). Immunohistochemical studies were also performed, and we observed that, adjacent to the decidual cells and villi invading the myometrium, there were numerous neoformation vessels immunolabelled with anti-CD34 antibody, leading to marked bleeding from this level during the operative procedure (Figure 3C. Microscopic sections at the placental invasion area in the myometrial structure). We labeled myocytes with anti-a-SMA antibody that revealed alpha-actin of smooth muscle to observe how the presence of placental structures disrupted the myometrium (Figure 3D. Microscopic sections at the placental invasion area in the myometrial structure).

Discussion

Placenta praevia is an obstetrical condition that can result in serious maternal and fetal complications. This obstetrical condition has been reported in 3-20 pregnancies out of 1000 reported. This wide variation in prevalence rate is attributed to the different degrees of PP, methods and timing of diagnosis, and the diversity of patients included in the studies(15).

Clinical and epidemiological studies have reported that placenta praevia is more common among older pregnant women, multiparous women, those who have previously given birth by caesarean section, those with multiple spontaneous or induced abortions, and in smokers or drug users during pregnancy(15).

Atherosclerotic changes in the uterine blood vessels have been cited in pregnant elderly women, leading to compromised uteroplacental blood flow through the development of large placental infarcts. To maintain optimal blood flow, a larger area of the uterine wall may be required for placenta attachment, which may lead to implantation of the placenta in the lower uterine segment(16). Our study observed that the age of patients with PP-C-a, PP-C-i or PP-C-p showed a significant difference of about 10 years compared to patients without accreta.

Our results also show a higher risk of placenta praevia in multiparous patients, confirming findings from previous studies. This is explained by areas of endometrial fibrosis where previous placentas were attached, with decreased local vascular density, which may lead to migration of placental villi to sites with denser vascular structures and the occurrence of PP. This may result in a larger placenta, which descends towards the internal cervical os or even covers it(17). Our research highlighted that over 60% of the PP patients investigated were multiparous. It was also reported that the multiparous are likely to be more elderly and that it is possible that advanced maternal age and multiparity are not independent risk factors for PP risk. This combined effect of the two risk factors was demonstrated in a large cohort study (n=37,956,020) conducted in the United States of America between 1989 and 1998(18). This study demonstrated that the risk of developing PP was not independent of maternal age and parity but rather that both factors exerted a common influence on the development of PP. In other words, increasing maternal age and multiparity conferred the highest risk of developing placenta praevia compared to the young primigravid group(18).

The history of caesarean delivery and the presence of repeated miscarriages led to an increased risk of PP through the presence of endometrial and myometrial lesions and scarring following surgery, with the development of fibrosis and local vascular deficit, demonstrated by a meta-analysis that corroborated the general findings reported in previous studies. These histopathological changes led to the migration of the placental villi to lower areas of the uterus, where vascularization was more intense(19). In the case of our study, we observed that the risk of PP increased due to the fibrosis arising after caesarean section, but also due to the thinning of the myometrial layer. We also noted that most PP-C-h or PP-C-0 were associated with CS birth in the antecedent. The increase in the number of uterine surgeries led in this study to the appearance of signs of accreta, and the degree of invasiveness increased with the number of caesarean births. Also, the percentage of cases with PP increased significantly with the number of previous abortions, consistent with the results of the studies mentioned before(19).

A higher risk of developing placenta praevia has been reported in pregnant smokers during pregnancy(17). A bigger placenta was observed among pregnant smokers, and this was caused by the vasoactive properties of nicotine and chronic hypoxia associated with carbon monoxide(20-22). Placental growth was more frequently associated with implantation near the internal cervical os(23,24). In this study, we observed that over 80% of patients in each class and subclass were tobacco users.

Previous research has shown that dichorionic twin pregnancies have a higher incidence of PP compared to monochorionic twin pregnancies. This is attributed to the doubling of implantation sites, as opposed to the simple increase in placental mass(25). Ananth et al. used US birth data and compared the incidence of placenta praevia among twin and singleton pregnancies, and they observed that the incidence of PP in twin pregnancies was 0.39%, representing a 40% increase compared to singleton pregnancies(26). Also, our study found twin pregnancies associated with PP, but the low number does not allow us to draw safe conclusions.

Male fetal sex has also been reported as a risk factor for developing placenta praevia(27-34). Several hypotheses have been proposed to support this: early or delayed fertilization during the menstrual cycle, change of implantation site(31), differences between transplacental hormones, and immunological status of pregnancies with female or male fetuses(35,36). A meta-analysis reported a 14% increase in PP among pregnancies with male fetuses(34). It was also found that eight of the nine studies reviewed reported an 11% increase in placenta praevia incidence among pregnancies with male fetuses in the Quebec population, thus making the correspondence between PP and male fetuses feasible(34-36). These correspondences have also been blamed on the higher weight of male compared to female fetuses, thus leading to increased placental surface area and increased risk of placenta praevia(37-41). The pathophysiological mechanism underlying this association with male sex is unknown. MacCiLLivray et al.(31) hypothesized that early or late insemination during the menstrual cycle may lead to an increase in male conception and may also result in a change in the implantation site. Major differences in transplacental hormones and immunological status exist between women carrying male and female fetuses. These fetal differences have led to pregnancy complications. Salzmann(35) reported that maternal intolerance of male fetal hormones can result in the development of preeclampsia(35). Noria et al.(36) observed factor V deficiency in pregnancy associated with Rh and PP immunization. Performing biochemical and immunological tests in PP-associated pregnancies and comparing the results provided important information about the pathophysiological mechanism of placenta praevia in pregnancies with male fetuses(36). Our study observed that over 50% of pregnancies were associated with male fetuses, similar to previously reported studies.

Ultrasound diagnosis of PP has been reported with a frequency of 5% in the second trimester of pregnancy and with a frequency of 0.3% at term. This is due to the enlargement of the lower segment of the uterus and upward migration of the bowel. In the case of scarring of the lower segment, the incidence of placenta praevia increases due to failure of placental migration(42-44). In 2016, The European Working Group on Abnormally Invasive Placenta proposed standardized descriptions of ultrasound signs used for the prenatal description of ultrasound signs, such as loss of retroplacental hypoechoic area(44,45), representing an abnormal extension of placental villi through the basal decidua into the myometrium, and it has been used by many authors as an ultrasound marker in cases of placenta praevia with accreta(46). Thinning of the myometrium to less than 1 mm or non-detection has been suggested as a prenatal diagnostic sign for PP-C, but it has been reported in only 50% of cohort studies(46). Numerous large, irregular and sonolucent intraplacental lacunae are the most common sonographic features associated with PP-C(45,47-49), giving the placenta a moth-eaten appearance in 80% of cases(46). Other sonographic signs suggestive of uterine wall invasion are the presence of bladder wall discontinuity, placental bulge, exophytic mass, subplacental and/or uterovesical hypervascularity, placental lacunae feeder vessels, and bridging vessels(50).

A defect of the trophoblast leading to excessive invasion into the myometrium has been reported microscopically(50). Another issue was a secondary defect of the endometrial-myometrial interface, leading to a failure of normal decidualization in the uterine scar, which allowed abnormally deep placental attachment with invasion of villi and trophoblast infiltration into the myometrium(48). With the occurrence of PP and myometrial invasion, intrapartum bleeding from the adherent zone has been reported(50), which we also noted in this study, where we observed that approximately 70% of patients bled before delivery. Their mean hemoglobin was lower compared to that of patients who did not bleed. By histopathological analysis, we observed, according to previous studies(38), that in PP samples there are extensive areas of placental infarction that led to the migration of villi to the internal cervical os and the development of placenta praevia.

We also noted in cases associated with PP-C-a, PP-C-I and PP-C-p the presence of villi in the myometrial structure, which led to disorganization of the uterine wall, the anarchic distribution of myocytes immunolabelled with anti-a-SMA antibody among villi and decidual cells, as well as the appearance and increased density of neoformation vessels immunolabelled with anti-CD34 antibody in the areas of accreta, which led to morbid adherence and massive bleeding from the placental site intraoperatively, leading to the necessity to perform hysterectomies.

Conclusions

The risk factors leading to placenta praevia were multiparity, an increased number of previous abortions, advanced maternal age, previous caesarean section births, the presence of twin pregnancies or pregnancies with male fetuses, tobacco use in pregnancy, and the degree of uterine invasiveness increased with the number of previous CS births.

The most important ultrasound features associated with placenta praevia with accreta were the loss of retroplacental hypoechoic area, the presence of placental lacunae, the presence of bladder wall discontinuity, placental bulge, exophytic mass, subplacental and/or uterovesical hypervascularity, placental lacunae feeder vessels, and bridging vessels. These may put doctors on alert and, thus, dictate the appropriate therapeutic management to prevent complications that could endanger fetal or maternal life.

According to the degree of placental invasiveness, the histopathological examination showed disorganization of the uterine wall, anarchically distributed myocytes among the villi and decidual cells, invasion of the myometrium by neoformation vessels, and these aspects led to morbidly adherent placenta and significant antepartum and intrapartum bleeding.

By analyzing and corroborating these clinical and ultrasonographic, as well as histopathological aspects, we could ensure prophylactic management to minimize the risks associated with massive bleeding at birth and those associated with emergency hysterectomies.

Corresponding authors: Elena-Iuliana-Anamaria Berbecaru, e-mail: iuliaberbecaru@gmail.com; George-Lucian Zorilă, e-mail: zorilalucian@gmail.com

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

-

Cresswell JA, Ronsmans C, Calvert C, Filippi V. Prevalence of placenta previa by world region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18(6):712–724.

-

Thomas JB. Obstetric haemorrhage. In: Steven GG, Jennifer RN, Joe LS editors. Obstetrics normal and problem pregnancies. 3rd Edition. New York: Churchill Livingstone: 1996:499-532.

-

Crane JM, Van Den Hof MC, Dodds L, Armson BA, Liston R. Neonatal outcomes with placenta previa. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(4):541–4.

-

Naeye RL. Placenta previa: predisposing factors and effects on the fetus and the surviving infants. Obstet Gynecol. 1978;52(5):52–5.

-

Wolf EJ, Mallozzi A, Rodis JF, Egan JF, Vintzileos AM, Campbell WA. Placenta previa is not an independent risk factor for a small for gestational age infant. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77(5):707–9.

-

Neri A, Gorodesky I, Bihari C, Ovadia Y. Impact of placenta previa on intrauterine fetal growth. Isr J Med Sci. 1980;16(6):429–32.

-

Marcellin L, Delorme P, Bonnet MP, Grange G, Kayen G, Tsatsaris V, Goffinet F. Placenta percreta is associated with more frequent severe maternal morbidity than placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(2):193.e1–9.

-

Collins SL, Alemdar B, van Beekhuizen HJ, Bertholdt C, Braun T, Calda P, Delorme P, Duvekot JJ, Gronbeck L, Kayem G, Langhoff-Roos J, Marcellin L, Martinelli P, Morel O, Mhallem M, Morlando M, Noergaard LN, Nonnenmacher A, Pateisky P, Petit P, Rijken MJ, Ropacka-Lesiak M, Schlembach D, Sentilhes L, Stefanovic V, Strindfors G, Tutschek B, Vangen S, Weichert A, Weizsäcker K, Chantraine F; International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta (IS-AIP). Evidence-based guidelines for the management of abnormally invasive placenta: recommendations from the International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(6):511–26.

-

Bi S, Zhang L, Wang Z, Chen J, Tang J, Gong J, Xie S, Lin L, Ren L, Zeng S, Huang L, Wang S, Du L, Chen D. Effect of types of placenta previa on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a 10-year retrospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;304(1):65–72.

-

Breen JL, Nuebecker R, Gregori CA, Franklin Jr JE. Placenta accreta, increta and percreta. A survey of 40 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1977;49(1):43-47.

-

Clark SL, Koonings PP, Phelan JP. Placenta previa/accreta and prior caesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66(1):89–92.

-

Karami M, Jenabi E, Fereidooni B. The association of placenta previa and assisted reproductive techniques: a meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31(14):1940–1947.

-

Crane JM, Van den Hof MC, Dodds L, Armson BA, Liston R. Maternal complications with placenta previa. Am J Perinatol. 2000;17(2):101–5.

-

Pătru CL, Marinaş MC, Tudorache Ş, Căpitănescu RG, Sîrbu OC, Zorilă GL, Cernea N, Istrate-Ofiţeru AM, Roşu GC, Iovan L, Iliescu DG. The performance of hyperadherence markers in anterior placenta previa overlying the Caesarean scar. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2019;60(3):861–867.

-

Faiz AS, Ananth CV. Etiology and risk factors for placenta previa: an overview and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Matern Fetal and Neonatal Med. 2003;13(3):175–190.

-

Williams MA, Mittendorf R. Increasing maternal age as a determinant of placenta previa: more important than increasing parity? J Reprod Med. 1993;38(6):425–8.

-

Naeye RL. Placenta previa: predisposing factors and effects on the fetus and the surviving infants. Obstet Gynecol. 1978;52(5):521–5.

-

Ananth CV, Demissie K, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. Placenta previa in singleton and twin births in the United States, 1989 through 1998: a comparison of risk factor profiles and associated conditions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):275–81.

-

Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. The association of placenta previa with history of cesarean delivery and abortion: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(5):1071–8.

-

Rose GL, Chapman MG. Aetiological factors in placenta previa – a case controlled study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;93(6):586–8.

-

Naeye RL. Maternal age, obstetric complications and outcome of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;61(2):210–16.

-

Christianson R. Gross differences observed in placenta of smokers and non-smokers. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110(2):178–87.

-

Williams MA, Mittendorf R, Leiberman E, Monson RR, Schoenbaum SC, Genest DR. Cigarette smoking during pregnancy in relation to placenta previa. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165(1):28–32.

-

Naeye RL. Effects of maternal cigarette smoking on the fetus and placenta. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1978;85(10):732–7.

-

Harper LM, Odibo AO, Macones GA, Crane JP, Cahill AG. Effect of placenta previa on fetal growth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):330.e1–5.

-

Ananth CV, Demissie K, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. Placenta previa in singleton and twin births in the United States, 1989 through 1998: a comparison of risk factor profiles and associated conditions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):275–81.

-

Record RC. Observations related to the aetiology of placenta previa with special reference to the influence of age and parity. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1956;10(1):19–24.

-

Rhodes P. Sex of the fetus in antepartum haemorrhage. Lancet. 1965;2(7415):718–719.

-

Hibbard BM. Foetal sex in antepartum haemorrhage. Lancet. 1965;2(7419):955–956.

-

Brenner WE, EdeLman DA, Hendricks CH. Characteristics of patients with placenta previa and results of ‘expectant management’. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978;132(2):180–91.

-

MacGillivray I, Davery D, Isaacs S. Placenta previa and sex ratio at birth. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292(6517):371–2.

-

Jakobovits AA, Zubek L. Sex ratio and placenta previa. Acta Obstet et Gynecol Scand. 1989;68(6):503–505.

-

Alberman ED, Butler NR, Kerr M, Rashad MN. Sex ratio and bleeding in pregnancy. Lancet. 1966; 7439(1):711.

-

Demissie K, Breckenridge MB, Joseph L, Rhoads CC. Placenta previa: preponderance of male sex at birth. Am J Epidemiol. 1999; 149(9):824–830.

-

Salzmann KD. Do transplacental hormones cause eclampsia? Lancet. 1955;ii:953–956.

-

Noia C, De CaroLis S, De Stefano V, Eerrazzani S, De Santis L, Carducci B, et al. Factor V deficiency in pregnancy complicated by Rh immunization and placenta previa. A case report and review of the literature. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76(9):890–892.

-

Berceanu C, Ciurea EL, Cirstoiu MM, Berceanu S, Ofiţeru AM, Mehedinţu C, Berbece SI, Ciortea R, Stepan AE, Balşeanu TA. Maternal-fetal management in trombophilia related and placenta-mediated pregnancy complications. Rev Chim. 2018;69(9):2396–2401.

-

Voicu NL, Bohîlţea RE, Berceanu S, Busuioc CJ, Roşu GC, Paitici Ş, Istrate-Ofiţeru AM, Berceanu C, Diţescu D. Evaluation of placental vascularization in thrombophilia and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2020;61(2):465-476.

-

Istrate-Ofiţeru AM, Berceanu C, Berceanu S, Busuioc CJ, Roşu GC, Diţescu D, Grosu F, Voicu NL. The influence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and gestational hypertension (GH) on placental morphological changes. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2020;61(2):371-384.

-

Berceanu C, Tetileanu AV, Ofiţeru AM, Brătilă E, Mehedinţu C, Voicu NL, Szasz FA, Berceanu S, Vlădăreanu S, Navolan DB. Morphological and ultrasound findings in the placenta of diabetic pregnancy. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2018;59(1):175–186.

-

Berceanu C, Mehedinţu C, Berceanu S, Voicu NL, Brătilă E, Istrate-Ofiţeru AM, Navolan DB, Niculescu M, Szasz FA, Căpitănescu RG, Văduva CC. Morphological and ultrasound findings in multiple pregnancy placentation. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2018;59(2):435–453.

-

Clark SL, Koonings PP, Phelan JP. Placenta previa/accreta and prior caesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66(1):89–92.

-

Wexler P, Gottesfeld KR. Early diagnosis of placenta previa. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;54(2):231–239.

-

Pasto ME, Kurtz AB, Rifkin MD, Cole-Beuglet C, Wapner RJ, Goldberg BB. Ultrasonographic findings in placenta increta. J Ultrasound Med. 1983;2(4):155–9.

-

Kerr de Mendonça L. Sonographic diagnosis of placenta accreta. Presentation of six cases. J Ultrasound Med. 1988;7(4):211–5.

-

Jauniaux E, Collins SL, Jurkovic D, Burton GJ. Accreta placentation. A systematic review of prenatal ultrasound imaging and grading of villous invasiveness. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(6):712–21.

-

Jauniaux E, Jurkovic D. Placenta accreta: pathogenesis of a 20th century iatrogenic uterine disease. Placenta. 2012;33(4):244–51.

-

Finberg HJ, Williams JW. Placenta accreta: prospective sonographic diagnosis in patients with placenta previa and prior cesarean section. J Ultrasound Med. 1992;11(7):333–43.

-

Comstock CH, Love JJ Jr, Bronsteen RA, Lee W, Vettraino IM, Huang RR, Lorenz RP. Sonographic detection of placenta accreta in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(4):1135–40.

-

Jauniaux E, Collins S, Burton GJ. Placenta accreta spectrum: pathophysiology and evidence-based anatomy for prenatal ultrasound imaging. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(1):75–87.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Placenta accreta – o preocupare tot mai mare în epidemia de operaţii cezariene

În ultimii ani, este de remarcat creşterea îngrijorătoare a numărului de operaţii cezariene efectuate la nivel global. Această intervenţie urmează ...

Cystic hygroma presenting as an isolated malformation – case report and literature review

Nuchal translucency (NT) is the ultrasound observation of subcutaneous fluid accumulation at the back of the fetal neck. When this accumulation be...

Management of placenta praevia percreta – a case report

Placenta percreta is a severe obstetrical condition of the placenta accreta spectrum (PAS), associated with a high rate of maternal morbidity and m...

Actualizări privind spectrul de placentă accreta – de la diagnostic la tratament

Spectrul de placentă accreta (PAS), cunoscut şi sub numele de „placenta cu aderenţă morbidă”, reprezintă o entitate patologică ce cuprinde diferit...