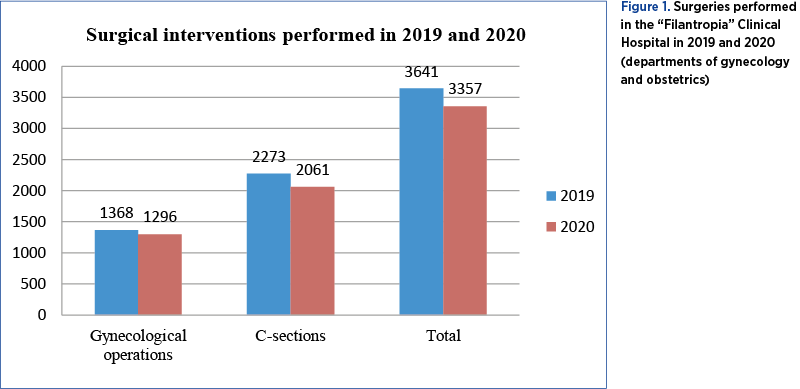

Background. The COVID-19 pandemic has put an important strain on the healthcare system all over the world. Several strategies to mitigate its impact have been proposed, with the sole purpose to prioritize the finite resources in different healthcare settings, in order to still provide qualitative medical services. As a result, elective surgeries, even for oncologic patients, were postponed or even cancelled, if the patient’s healthcare safety could not be maintained. Surgical site infections (SSIs), as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), are a well-known cause of patient morbidity and of increased healthcare costs. Objectives. To assess the rate and impact of SSIs during the COVID-19 pandemic (the year 2020) compared to the rate during 2019 and to identify the prevention bundle to reduce their incidence in an important academic tertiary center in Romania. Materials and method. We performed a cohort study on operated patients in both obstetrics and gynecology departments, in a third-level maternity unit, the “Filantropia” Clinical Hospital of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Bucharest, regarding the prevalence of surgical site infections during one year of COVID-19 pandemic (2020) versus the prevalence and impact of the previous year (2019). This is an observational cohort retrospective study, analyzing the period from the 1st of January 2019 to the 31st of December 2019 and from the 1st of January 2020 to the 31st of December 2020, with the aim to evaluate the influence of highly surveillance and perioperative guidelines followed during the COVID-19 pandemic and to compare it to the regulations and guidelines followed during 2019. Results. Taking into account both gynecological interventions and caesarean sections, 6998 interventions were performed (3641 in 2019 and 3357 in 2020), with no significant difference regarding patients’ demographics. The number of operations performed were different, with fewer caesarean sections in 2020 (2061) compared to 2273 in 2019. Also, fewer operations for malignancies such as ovarian or endometrial cancers and laparoscopic procedures were performed in 2020 compared to 2019, due to difficulties in maintaining the patients’ and medical personnel safety. No significant difference rates were observed regarding postoperative complications or the length of stay. However, the total SSI complication rate was reduced in 2020 (1.22%) compared to the previous year (1.92%) due to the introduction of higher surveillance protocols and to medical personnel theoretical and hands-on education. Discussion. Risk factors, such as high Body Mass Index, increased blood glucose levels, smoking status, immunodeficiency or MRSA status, have an important role in facilitating the SSIs. Considering the epidemiological context, a reduced referral to medical services during pandemic, excluding emergencies, led to fewer surgeries performed in the gynecology department, fewer caesarean sections and to a total SSI rate decreased compared to 2019. Thus, understanding the multiple factors involved in the pathology, the importance of a responsible care and the existence of a record of these cases may help diminish the rate, especially during pandemic. Conclusions. Beside challenges faced during the pandemic period, we continued to perform surgical procedures with timely planning and meticulous care, keeping a low rate of SSIs (1.22%). The use of standardized protocols and a bundle of preventive strategies may be of great help in the better control of this type of infections.

Infecţiile asociate plăgilor operatorii în pandemia de COVID-19: un studiu comparativ

Surgical site infections in the COVID-19 era: a comparative cohort study

First published: 25 aprilie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.69.2.2021.4985

Abstract

Rezumat

Introducere. Pandemia de COVID-19 a impus noi abordări, cu singurul scop de a prioritiza resursele în oferirea, în continuare, de servicii medicale calitative. Intervenţiile chirurgicale elective, chiar şi pentru pacienţii oncologici, au fost amânate sau chiar anulate, dacă nu s-a putut menţine siguranţa medicală a pacientului. Infecţiile asociate plăgilor (SSI), aşa cum sunt definite de Centrul pentru Prevenirea şi Controlul Bolilor (CDC), sunt o cauză bine cunoscută de morbiditate în cazul pacienţilor şi a costurilor crescute ale asistenţei medicale. Obiective. Evaluarea ratei şi a impactului infecţiilor asociate plăgilor în timpul pandemiei de COVID-19 (anul 2020) faţă de rata din 2019 şi identificarea metodelor de prevenţie pentru a reduce incidenţa acestora într-un centru terţiar din România. Materiale şi metodă. Am efectuat un studiu de cohortă la pacienţi operaţi în secţiile de obstetrică şi ginecologie din cadrul Spitalului Clinic de Obstetrică şi Ginecologia „Filantropia”, Bucureşti, cu privire la prevalenţa infecţiilor asociate plăgilor, pe parcursul unui an al pandemiei de COVID-19 (2020), comparativ cu prevalenţa şi impactul din anul precedent (2019). Acesta este un studiu retrospectiv, observaţional, care analizează perioada de la 1 ianuarie 2019 până la 31 decembrie 2019 şi de la 1 ianuarie 2020 până la 31 decembrie 2020, cu scopul de a evalua influenţa supravegherii înalte şi a implementării ghidurilor perioperatorii în timpul pandemiei de COVID-19, în comparaţie cu măsurile abordate în anul precedent. Rezultate. Luând în considerare atât intervenţiile ginecologice, cât şi operaţiile cezariene, au fost efectuate 6998 de intervenţii (3641 în 2019 şi 3357 în 2020), fără o diferenţă semnificativă privind demografia pacientului. Numărul de operaţii efectuate a fost diferit, cu mai puţine operaţii cezariene în 2020 (2061) comparativ cu 2273 în anul 2019. De asemenea, s-au efectuat mai puţine operaţii pentru tumori maligne, precum cancerul ovarian sau cel endometrial, şi proceduri laparoscopice în 2020 comparativ cu 2019, din cauza dificultăţilor în menţinerea siguranţei pacientului şi a personalului medical. Nu s-au observat diferenţe semnificative privind complicaţiile postoperatorii sau durata spitalizării. Cu toate acestea, rata totală a complicaţiilor SSI a fost redusă în 2020 (1,22%) comparativ cu anul precedent (1,92%), ca urmare a introducerii unor protocoale de supraveghere superioare şi a educaţiei teoretice şi practice a personalului medical. Discuţie. Factorii de risc, cum ar fi indicele crescut de masă corporală, nivelul glicemiei, statusul privind fumatul, imunodeficienţa sau infecţiile MRSA (stafilococul auriu multirezistent la antibiotice), au un rol important în facilitarea SSI. Având în vedere contextul epidemiologic, o adresare mai redusă la servicii medicale în timpul pandemiei, excluzând situaţiile de urgenţă, a condus la mai puţine operaţii efectuate în secţia de ginecologie, la mai puţine cezariene şi la o rată totală a SSI mai scăzută comparativ cu 2019. Astfel, înţelegând factorii multipli implicaţi în patologia acestor infecţii, este evidentă importanţa unor îngrijiri responsabile şi a existenţei unei baze de date cu documentarea clară a acestor cazuri. Concluzii. Dincolo de provocările apărute în timpul pandemiei, am continuat să efectuăm proceduri chirurgicale planificate, cu o îngrijire minuţioasă, păstrând o rată scăzută a SSI, de 1,22%. Utilizarea protocoalelor standardizate şi a unui pachet de strategii preventive a fost de un real folos pentru controlul mai bun al acestui tip de infecţii.

Introduction

Surgical site infections (SSIs), as defined by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), are infections associated to an operative procedure at the site of incision (superficial or deep) or at the site of an organ opened or manipulated during a surgical procedure, within 30 days(1). In superficial incisional SSIs, the infection involves only skin and subcutaneous tissue, while deep incisional SSIs involve fascial and muscle layers(2,3).

SSIs are a well-known cause of patients’ morbidity and mortality. The current literature mentions a 2% to 5% rate of infections for all surgeries, including approximately 2% of hysterectomies(4,5). However, the registered rate is still unknown due to the fact that these infections appear after hospital discharge and many patients tend to present to other hospital for care. Not only the increase in mortality and morbidity is noticed, but also the healthcare costs. Surveillance over risk factors is demonstrated to be effective in reducing the risk of hospital-acquired infections.

Materials and method

We performed a cohort study on operated patients in both obstetrics and gynecology departments, at a third-level maternity unit, “Filantropia” Clinical Hospital of Obstetrics and Gynecology, in Bucharest, regarding the prevalence of SSIs during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to its prevalence a year before (in 2019). This is an observational retrospective study performed on data extracted from digital electronic health records from the 1st of January 2019 to the 31st of December 2019 and from the 1st of January 2020 to the 31st of December 2020 to evaluate the influence of high surveillance during the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of known risk factors on the development of more severe SSI cases, and the management of patients suffering from SSIs.

Results

Patient demographics

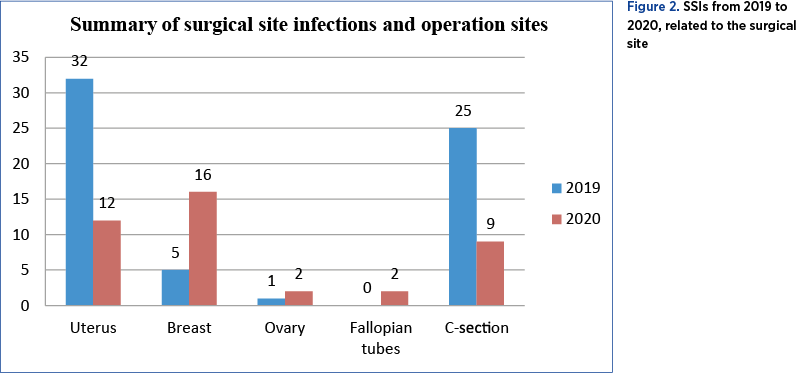

During the study period, 6998 interventions were performed (3641 in 2019, with 2273 caesarean sections and 1368 operations in the Department of Gynecology; and 3357 in 2020, with 2061 caesarean sections and 1296 operations in the Department of Gynecology), with no significant difference regarding patient’s demographics (Figure 1). The majority of patients operated in the Department of Gynecology were over 60 years old, overweight or obese, with multiple comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus or cardiovascular diseases. Approximately one third of patients operated on the Department of Obstetrics share a high Body Mass Index (BMI) that may complicate the interventions.

COVID-19 status

According to the protocol of our hospital, patients underwent the preoperative screening for symptoms of COVID-19 using a standardized questionnaire and, from April 2020, the preoperative testing with nasopharyngeal swabs was introduced and the patients were required to provide a maximum of seventy-two hours issued reverse-transcriptase polymerase-chain reaction (RT-PCR) SARS-CoV-2 negative test result before being admitted for surgery. Patients undergoing mild interventions, that did not require general anesthesia or intubation, were admitted for surgery after performing an antigen SARS-CoV-2 test with a negative result during the day prior to the operation. If tested positive and the operation or caesarean section needed to be done, they were referred to a specific COVID-19 unit.

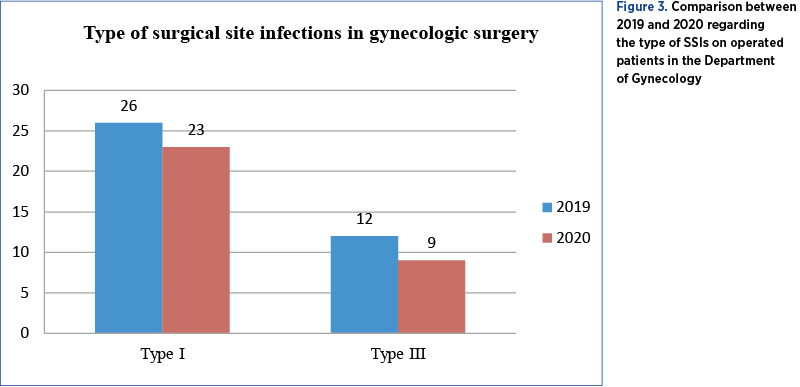

Out of the 1296 interventions performed in the Department of Gynecology in 2020, 32 patients (2.469%) developed SSIs, 23 (1.774%) of them registered with type I SSIs and 9 (0.694%) with type III SSIs (Figure 3). Regarding the Department of Obstetrics, 2061 caesarean sections were performed in 2020, with 9 women (0.436%) developing SSIs, 7 of them (0.339%) presenting with type I and only two (0.097%) of them with type III SSIs. Analyzing the electronic records of patients operated on in 2020, we discovered that there were 16 cases (50%) out of 32 that presented type I infections after breast surgery, two patients (6.25%) developed infections after surgery of the ovaries (one of type I and one of type III), 12 patients (37.5%) out of 32 developed infections after surgery on uterus, with a majority of eight (25%) having type III infections and two patients (6.25%) developing type I infections after surgeries performed on the fallopian tubes.

Due to the fact that 50% of SSIs registered in the Department of Gynecology were related to breast surgery (Figure 2), it is appropriate to mention the factors that could produce risks, such as: previous breast biopsy, intraoperative bleeding, postoperative drainage, and drainage time. However, the immediate reconstruction, axillary lymph node dissection or previous chemotherapy or corticotherapy showed no further influence on SSIs(6). A number of 16 patients with gynecologic diseases were excluded from the study because they did not match the selection criteria. Hysterectomy or any other surgery addressed to the uterus was the second most frequent surgery associated with risks for SSIs, therefore it is understandable the potential prejudice to the organism. The potential pathogens associated with this type of infections could come from the skin or ascend from the vagina and endocervix to the operative site, causing vaginal cuff cellulites, pelvic cellulites or abscesses(7).

Evaluating the bacterial species involved, we discovered that the most frequent isolated germ from cultures was Staphylococcus epidermidis, followed by Staphylococcus aureus.

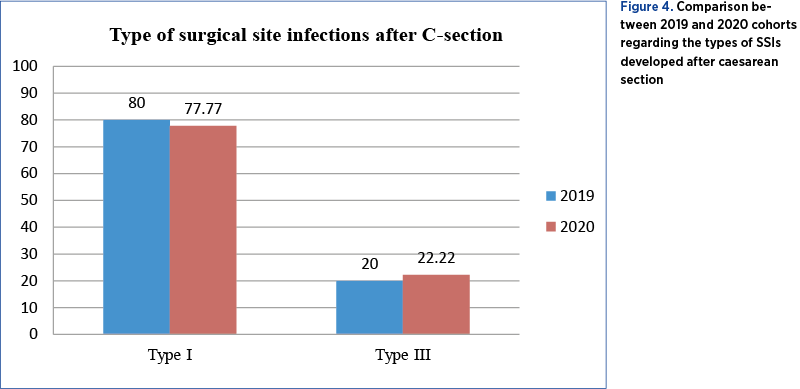

On the other hand, out of 1368 surgeries performed in the Department of Gynecology in 2019 (more than in 2020), 38 patients (2.77%) developed SSIs, 26 of them (1.90%) registered with type I SSIs and 12 (0.877%) with type III SSI. Regarding the Department of Obstetrics, 2273 caesarean sections were performed all over the year, with 25 women (1.09%) developing SSIs, 20 of them (0.879%) presenting with type I and five (0.219%) with type III SSIs – as observed, an increase in every percentage compared to 2020 (Figure 4). Also, by analyzing the electronic records of operated patients in 2019, we discovered 32 cases out of 38 (84.21%) who developed SSIs after surgery on the uterus, with 21 cases (55.26%) presenting type I infections, 9 cases (23.68%) developing type III infections (vaginal cuff abscess and two cases with infection affecting the peritoneum); five patients (13.15%) developed type I infections after breast surgery, and one patient (2.63%) out of 38 developed a type III infection after ovarian surgery (Figure 3). Being another epidemiological context, more surgical interventions were performed in the field of gynecologic oncology, explaining the higher rate of SSIs of this type, compared to the ones related to the breast in 2020.

Because more than 75% of SSIs registered in the Department of Gynecology were associated with hysterectomy (Figure 2), it is appropriate to mention the factors that could reduce risks, such as the long duration of the operation, a wider open area exposed to germs, intraoperative bleeding, postoperative drainage and drainage time. A number of 14 patients (seven with Bartholin gland abscesses and seven with postpartum mastitis) did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded from the study. As for the most frequent isolated germ, Staphylococcus aureus occupied the first place, followed by Staphylococcus epidermidis.

Discussion

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed the classification of SSIs, including clinical symptoms and diagnosis criteria. Type I is represented by the superficial incisional infection that appears within 30 days, characterized by tenderness and peri-incisional pain, swelling, erythema or heat. For diagnosis, at least one symptom is requested and one of the following: purulent drainage, positive culture for a microorganism, incision opened by the surgeon, under the concern of superficial SSI. Type II is the deep incisional infection that affects the fascia or the muscle, appearing with 30 up to 90 days and characterized by fever (>38°C) and localized pain or tenderness. The diagnosis in this case is given by the purulent discharge, wound dehiscence or intentionally opened by a surgeon and positive culture. Type III is the organ/space SSI appearing within 30 up to 90 days, characterized by specific symptoms like fever (>38°C), hypotension, nausea and vomiting, pain or tenderness or even elevated levels of transaminases. The diagnosis combines specific symptoms with at least one of the following: purulent drainage, positive cultures, abscesses or different collections and radiological imagining suggestive of infections(1).

The risk factors that may impact the SSIs are numerous. Obesity contributes to surgical infection by limiting the surgical approach, prolonging the operative time, decreasing the absorption of preoperative antibiotics and by poor nutritional status(8,9). Obese women may benefit from subcutaneous sutures or vacuum drainage to prevent infections(10). Beside a high Body Mass Index, blood glucose level needs to be regulated prior to surgery, hyperglycemia in both diabetic and nondiabetic patients increasing the risk, being demonstrated that intensive glycemic control for 24 hours postoperative in diabetes mellitus patients may decrease the rate of SSIs by 35% compared to patients receiving intermittent sliding scale insulin(11,12). It is advisable to maintain the 6 a.m. blood glucose at 180 mg/dL or lower on postoperative days 1 and 2(13). Another risk factor that needs to be assessed before surgery is the smoking status, that can cause tissue ischemia and delayed wound healing. It is recommended to encourage smoke cessation within 30 days of the procedure(14,15). Time of wound exposure is another risk factor that has a high contribution on the appearance of SSIs; by exposing the area directly, although protected by sterile fields, to external pathogens or by altering the temperature regulation, can result in SSI. Especially when talking about surgery in gynecologic oncology, the immunodeficiency status must be checked prior to surgery. It can occur due to malnutrition, chemotherapy use, HIV infection or chronic treatments, in all cases the result being an impaired ability to fight the infection. It should be reminded that, when talking about surgical site infections, it is important to assess the antibiotic-resistance and, moreover, the MRSA status (being one of the most frequent germs involved). It is recommended to check the medical records and give strict surveillance for appropriate prophylactic therapy(16).

Despite the previously mentioned risks factors, the pandemic changed the rules of the game at several levels. Trying to prioritize resources in the healthcare system, many elective surgeries were put on hold or even cancelled, if no further prejudice. The remained ones were planned meticulously, deciding the time, place and mode of the surgery, in order to protect both patients and the medical personnel involved. Avoiding aerosol transmission from general anesthesia has led to changes in intraoperative pathways. Emerging evidence suggested the importance of minimizing the risks of hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection during the perioperative period. As for the oncologic patients, each case was managed by a multidisciplinary team, putting in balance both the advantages and the disadvantages of postponing and, when recommended, the intervention was made with suitable personal protective equipment (PPE). The same protective measures were taken in the Department of Obstetrics, to diminish the risk of acquiring SSIs.

Strategies for SSIs prevention

n Preoperative care and intraoperative care

In 2017, Pellegrini et al. described a consensus bundle regarding SSIs prevention in gynecologic surgery, made of four concepts: Readiness, Recognition and Prevention, Response, and Reporting and Systems Learning(17). The Readiness includes six areas of focus to prevent SSIs:

1. Standard preoperative care instructions and patient’s education prior to the surgery. Studies reveal that 40% up to 80% of the information given to the patient is forgotten immediately or retained incorrectly. This is due to the patient’s anxiety regarding the operation or because of the poor understanding of medical terms. Thus, any modality like verbal, written pamphlets, instruction sheets or videos should be used to increase compliance. The preoperative care and patient’s education should reunite the following: showering with an antimicrobial solution prior to surgery, not shaving before the procedure, not taking anything by mouth, knowing and controlling preexisting medical conditions, antibiotic administration, and a few information about the medical personnel involved, surrounding devices and immediate recovery(18).

2. Staff responsibility. Because the prevention of SSIs is part of a collective responsibility, each member of the perioperative team – namely, surgeons, anesthetists and the nursing team – should be advised to follow a protocol(19-21). Hand hygiene, use of sterile surgical attire and barrier devices, patient decolonization and skin cleansing with antiseptics are among the most important.

3. Temperature regulation is another area of interest in preventing SSIs. It includes the ambient operating room and the patient normothermia that is influenced by the type of anesthesia used. Current literature shows a decrease of about 1.6ºC in the first hour after the induction of general anesthesia. Preventing hypothermia is important due to the risk of decreased tissue oxygenation, impairment of immune function and altered metabolic needs(19).

4. Selection and timing of the administration of antibiotic prophylaxis. Studies proved that 30-60 minutes prior to skin incision is the best suitable period for complex gynecologic procedures with use of antibiotic regimen against the most likely infecting organisms, such as Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus species. Our protocol recommends a single dose of cephalosporin. It is important to check the MRSA status also for possible resistance.

5. Timing of discontinuation of prophylactic antibiotic. A second dose of antibiotic will be administered in case of blood loss more than 1.5 L, a duration of surgery longer than 3 hours or of obesity. There is no documented benefit in the reduction of surgical site infection after skin closure. Antibiotics should be continued only when clear medical indications are present(20).

6. Appropriate skin preparation. This is a critical step to follow in preventing SSIs. Shower with soap or an antiseptic agent the night or early in the morning before surgery is a simple and efficient recommendation(18).

Also, the preoperative care includes the Recognition concept of Pellegrini. As described before, the most frequent risks factors in gynecological surgery and in obstetrics are the blood glucose level, the high Body Mass Index, the smoking status, the nutritional status, the potential immunodeficiency and the MRSA status.

The Response domain involves the development of intraoperative timeouts to address antibiotic dosage, timing, prophylaxis issues, and patient-specific issues. There is a need to reassess the length of surgery, the blood loss, the potential bowel incision or vaginal contamination(21).

n Postoperative care

Before discharging the patient, a few postoperative care instructions should be offered by the medical personnel. The patient should be advised to take a proper care of the wound, avoiding excessive activities like stair climbing, exercising with dumb-bells, even driving, taking medication for pain management and schedule for follow-up visits. Also, the medical documents offered to the discharged patient should mention the urgent situations when the patient must present to the hospital: excessive bleeding and pain, site infections, fever, altered drainage or faintness.

The last concept of the prevention bundle created by Pellegrini is the Reporting and Systems Learning. There are a few elements to follow for a better management of the operated patient. Establish a culture of huddles, as described by Pellegrini, referring to a brief meeting to discuss possible events during surgery that may impact the patient afterwards. Secondly, creating a system to analyze, report and measure outcomes of surgical site infection for future better investigations on the subject. We need to encourage the ongoing feedback of SSIs and provide education and leadership to surgical and perioperative personnel for a better knowledge of the rate and possibilities to diminish it.

Despite challenges faced during 2020, we were able to maintain a high level of surgical care and face the difficulties of our patients, despite the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic which had a great impact on surgical services worldwide(22-25).

Limits of the study

In performing this study, we faced some limitations, because most of these infections manifested when the patients were discharged and some of them did not continue the follow-up in our clinic.

Conclusions

Surgical site infections are persistent and preventable healthcare-associated infections, with an increased demand for evidence-based interventions for prevention.

Consistent with the information provided, this cohort study reports a decreased rate of SSIs during the pandemic of 1.22%, compared to 1.92% in 2019. Maintaining the operating rooms active during the pandemic was possible with meticulous and timely planning, with appropriate personal protective equipment and use of standardized protocols. Also, we managed to minimize the SARS-CoV-2 transmission perioperatively by offering theoretical and hands-on training with PPE. But for the further peaks of the pandemic, the training of medical personnel, especially for the nursing staff, is required for the postoperative periods to enhance recovery and minimize the postoperative complications. The purpose of the present study is to demonstrate that, using a standard protocol, known and respected by each of the members of the perioperative team, can reduce the risks for surgical site infections, even in a difficult situation like the COVID-19 pandemic. We emphasize the teamwork, the shared responsibilities and the medical knowledge.

Bibliografie

-

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Surgical Site Infection (SSI) Event. 2016. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/ 9pscssicurrent.pdf. Accessed 13 Feb, 2021.

-

Berríos-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, et al. Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2017. JAMA Surg. 2017 Aug 1;152(8):784-791.

-

Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13(10):606-8.

-

Anderson DJ, Kaye KS, Classen D, et al. Strategies to prevent surgical site infections in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(suppl 1):S51-61.

-

Lake AG, McPencow AM, Dick-Biascoechea MA, Martin DK, Erekson EA. Surgical site infection after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:490.e1-9.

-

Xue DQ, Qian C, Yang L, Wang XF. Risk factors for surgical site infections after breast surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO). 2012;38(Issue 5):375-381.

-

Lachiewicz MP, Moulton LJ, Jaiyeoba O. Pelvic surgical site infections in gynecologic surgery. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2015;2015:614950.

-

Colling KP, Glover JK, Statz CA, Geller MA, Beilman GJ. Abdominal hysterectomy: reduced risk of surgical site infection associated with robotic and laparoscopic technique. Surg Infect. 2015;16:498-503.

-

Young H, Knepper B, Vigil C, Miller A, Carey JC, Price CS. Sustained reduction in surgical site infection after abdominal hysterectomy. Surg Infect. 2013;14:460-3

-

Committee opinion no. 619: Gynecologic surgery in the obese woman. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jan;125(1):274-278.

-

Al-Niaimi AN, Ahmed M, Burish N, Chackmakchy SA, Seo S, Rose S, et al. Intensive postoperative glucose control reduces the surgical site infection rates in gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecologic Oncology. 2015;136(1):71–76.

-

Richards JE, Kauffmann RM, Obremskey WT, May AK. Stress-induced hyperglycemia as a risk factor for surgical-site infection in non-diabetic orthopaedic trauma patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2013;27(1):16–21.

-

Deverick AJ, Podgorny K, Berríos-Torres SI, Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Greene L, Nyquist AC, Saiman L, Yokoe DS, Maragakis LL, Kaye KS. Strategies to Prevent Surgical Site Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2014;35(6):605-27.

-

Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(4):250–278.

-

Theadom A, Cropley M. Effects of preoperative smoking cessation on the incidence and risk of intraoperative and postoperative complications in adult smokers: a systematic review. Tob Control. 2006;15(5):352–358.

-

Kavanagh KT, Calderon LE, Saman DM, Abusalem SK. The use of surveillance and preventative measures for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in surgical patients. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 2014 May 14;3:18.

-

Pellegrini JE, Toledo P, Soper DE, Bradford WC, Cruz DA, Levy BS, Lemieux LA. Consensus Bundle on Prevention of Surgical Site Infections After Major Gynecologic Surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jan;129(1):50-61. Erratum in: Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jun;133(6):1288.

-

Nelson G, Bakkum-Gamez J, Kalogera E, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in gynecologic/oncology: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations – 2019 update. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer. 2019 May;29(4):651-668.

-

Nguyen N, Yegiyants S, Kaloostian C, Abbas MA, Difronzo LA. The Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) initiative to reduce infection in elective colorectal surgery: Which performance measures affect outcome? American Journal of Surgery. 2008;74(10):1012–1016.

-

Bratzler DW, Houck PM. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: An advisory statement for the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. American Journal of Surgery. 2005;189:395–404.

-

World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist. Available at: https://www.who.int/patientsafety/topics/safe-surgery/checklist/en/. Accessed on 19 Apr, 2021.

-

Ielpo B, et al. Global attitudes in the management of acute appendicitis during COVID-19 pandemic: ACIE Appy Study. Br J Surg. 2020 Oct 8;10.1002/bjs.11999.

-

An Y, et al. Surgeons’ fear of getting infected by COVID19: A global survey. Br J Surg. 2020;107(11):e543–e544.

-

Bellato V, et al. Screening policies, preventive measures and in-hospital infection of COVID-19 in global surgical practices. J Glob Health. 2020;10(2):1–15.

-

Bellato V, et al. Impact of asymptomatic COVID-19 patients in global surgical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2020;107(10):e364–e365.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Placenta accreta – o preocupare tot mai mare în epidemia de operaţii cezariene

În ultimii ani, este de remarcat creşterea îngrijorătoare a numărului de operaţii cezariene efectuate la nivel global. Această intervenţie urmează ...

Sarcina cicatricială după operaţia cezariană – o continuă dilemă terapeutică. Serie de cazuri şi review al literaturii

Sarcina cicatricială după operaţie cezariană (CSP) este o tulburare iatrogenă care pune viaţa în pericol, cu o incidenţă tot mai mare, din cauza cr...

O analiză a factorilor de risc pentru preeclampsie

Preeclampsia este o tulburare sistemică a sarcinii caracterizată prin diverse manifestări ale disfuncţiei organelor, asociată cu diverse afecţiuni ...

Tipuri actuale de naştere şi impactul lor asupra mamei şi fătului

În urma evoluţiei modalităţii de naştere, am constatat, potrivit unui studiu observaţional efectuat în clinica noastră în perioada 2017-2021, o ten...