Sleep and depression are two interconnected conditions that have a bidirectional relationship. While depression can lead to sleep problems, sleep disturbances can also trigger or worsen depression symptoms. Recognizing the interconnection between these conditions and addressing them concurrently may improve the treatment outcomes and the quality of life for patients.

Sleep and depression – understanding the bidirectional relationship

Somnul şi depresia – înţelegerea relaţiei bidirecţionale

First published: 30 iunie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.73.2.2023.8253

Abstract

Rezumat

Somnul şi depresia sunt două condiţii interconectate, aflate într-o relaţie bidirecţională una cu cealaltă. Pe de o parte, depresia poate afecta negativ calitatea somnului, dar şi tulburările de somn pot agrava simptomele depresiei sau pot fi un factor declanşator al acesteia. Conştientizarea interdependenţei dintre cele două condiţii şi abordarea lor concomitentă pot îmbunătăţi răspunsul la tratament şi calitatea vieţii pacienţilor.

Introduction

Sleep and depression are two interconnected conditions that have a bidirectional relationship. On one hand, depression can lead to sleep problems, including insomnia and hypersomnia, while on the other hand, sleep disturbances can trigger or worsen depression symptoms. Understanding this relationship is crucial in developing effective treatment plans for patients with either or both of these conditions.

Depression is a mental health disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, loss of interest in activities, and a range of physical and cognitive symptoms. Among the many symptoms associated with depression, sleep disturbances are common, affecting up to 90% of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD)(1). Insomnia, characterized by difficulty falling or staying asleep, is the most prevalent sleep problem in individuals with depression, while hypersomnia, or excessive sleepiness, is also common(2).

Several factors may contribute to the link between depression and sleep problems. The dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which controls the body’s stress response, is a key factor in depression and can also affect sleep quality and quantity(3). In addition, the disruption of circadian rhythms, the body’s internal clock that regulates sleep-wake cycles, may play a role in both depression and sleep problems(4).

While depression can lead to sleep problems, sleep disturbances can also trigger or worsen depression symptoms. Studies have shown that individuals with insomnia are at a higher risk of developing depression, compared to those without sleep problems(1). In addition, insomnia may also contribute to the persistence of depression symptoms and reduces the effectiveness of treatment.

The topography of normal sleep

Sleep is a complex process that can be divided into several stages, based on characteristic changes in brain wave activity and other physiological measures. Understanding the topography of normal sleep is essential for identifying and treating sleep disorders.

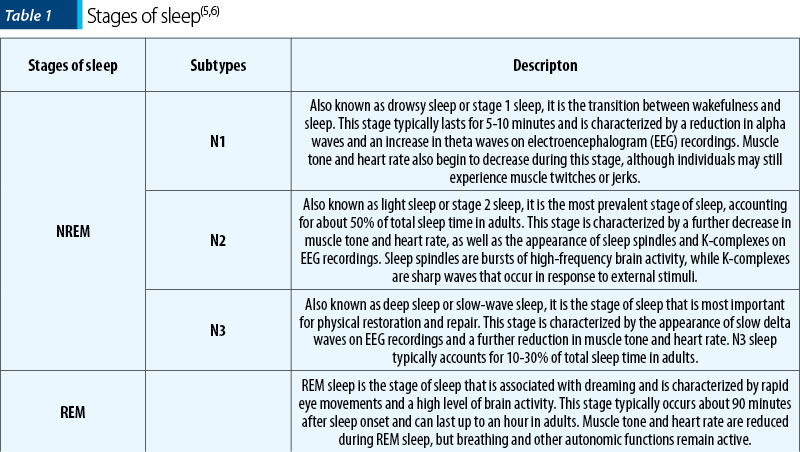

Normal sleep consists of two main stages: non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. NREM sleep can be further divided into three stages: N1, N2 and N3 (Table 1).

The topography of sleep refers to the distribution of different stages of sleep throughout the night. In healthy adults, sleep typically begins with N1 sleep and progresses through N2 and N3 sleep before returning to N2 and eventually entering REM sleep. This cycle typically repeats every 90 minutes throughout the night, with longer periods of N3 sleep occurring in the first half of the night and longer periods of REM sleep occurring in the second half. Understanding the topography of normal sleep is essential for identifying and treating sleep disorders.

Alterations of sleep neurophysiology in depression

Sleep disturbances are a common symptom of depression, affecting up to 90% of individuals with major depressive disorder(7). The relationship between depression and sleep is complex, with alterations in neurophysiology being observed in both disorders. Understanding the alterations of sleep neurophysiology in depression can provide insight into the pathophysiology of the disorder, as well as inform treatment approaches.

One of the primary alterations in sleep neurophysiology in depression is decreased slow-wave sleep (SWS). SWS is the deepest stage of non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, and is characterized by slow brain waves. It is thought to play a critical role in the restoration and recovery of the brain(8). In individuals with depression, SWS is often reduced or absent, which may contribute to the cognitive deficits and emotional dysregulation observed in the disorder(9).

Another alteration in sleep neurophysiology in depression is represented by the increased rapid eye movement (REM) sleep latency. REM sleep is the stage of sleep during which most dreaming occurs. In individuals with depression, REM sleep latency is often prolonged, meaning it takes longer to enter REM sleep(10). This may be due to alterations in the function of the brainstem, which is involved in regulating the transition between NREM and REM sleep(11).

Other alterations in sleep neurophysiology in depression include decreased REM sleep, increased stage 1 NREM sleep, and increased awakenings during the night(1). These alterations may contribute to the fatigue and daytime sleepiness often observed in individuals with depression(12).

The alterations in sleep neurophysiology observed in depression have important implications for treatment. Antidepressant medications have been shown to normalize sleep architecture in individuals with depression(13). Additionally, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) has been found to improve both sleep and depressive symptoms(14).

The alterations in sleep neurophysiology observed in depression, including decreased SWS and increased REM sleep latency, provide insight into the pathophysiology of the disorder. Understanding these alterations may inform treatment approaches and improve outcomes for individuals with depression.

Management of depressive insomnia

Depressive insomnia is a common symptom of major depressive disorder and can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life. Insomnia in depression is characterized by difficulty falling or staying asleep, early morning awakenings, and nonrestorative sleep. The management of depressive insomnia is an essential component of treating depression and improving overall outcomes for individuals with the disorder. In this article, we will discuss the management of depressive insomnia, including pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches, with relevant bibliographic references.

Pharmacological approaches to managing depressive insomnia include the use of sedative-hypnotic medications, such as benzodiazepines, non-benzodiazepine sedatives, and melatonin receptor agonists (MRA). These medications can help improve sleep quality and reduce sleep onset latency, but they should be used with caution due to the risk of dependence and adverse effects such as next-day sedation and cognitive impairment(15). The American College of Physicians (ACP) recommends the use of pharmacological therapy for insomnia only after nonpharmacological approaches have been attempted(16).

Nonpharmacological approaches to managing depressive insomnia include cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), which has been shown to be an effective treatment for both insomnia and depression(14). CBT-I typically involves addressing negative thoughts and behaviors related to sleep and implementing strategies to improve sleep hygiene, such as maintaining a consistent sleep schedule, avoiding caffeine and alcohol, and reducing exposure to electronics before bedtime. Other nonpharmacological approaches include mindfulness-based interventions, relaxation techniques, and sleep restriction therapy(17).

Combined pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches may also be effective for managing depressive insomnia. A study by Manber et al.(18) found that the combination of CBT-I and the sedative-hypnotic zolpidem resulted in greater improvements in sleep quality and depressive symptoms than either treatment alone.

Managing depressive insomnia is an essential component of treating depression and improving overall outcomes for individuals with the disorder. Pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches can both be effective in improving sleep quality, reducing insomnia symptoms and improving depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

Sleep problems and depression have a bidirectional relationship that requires a comprehensive and integrated approach to treatment. Recognizing the interconnection between these conditions and addressing them concurrently may improve the treatment outcomes and the quality of life for patients. Future research should focus on understanding the underlying mechanisms linking sleep problems and depression, and on developing targeted interventions to address these conditions.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

- Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1-3):10-19.

- Taylor DJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH. Insomnia as a health risk factor. Behav Sleep Med. 2003;1(4):227-247.

- Pariante CM, Lightman SL. The HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(9):464-468.

- LeGates TA, Fernandez DC, Hattar S. Light as a central modulator of circadian rhythms, sleep and affect. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(7):443-454.

- Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL Jr, Quan SF. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007.

- Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Los Angeles: Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute, University of California, 1968.

- Ohayon MM, Sagales T. Prevalence of insomnia and sleep characteristics in the general population of Spain. Sleep Med. 2010;11(10):1010-1018.

- Benca RM, Obermeyer WH, Thisted RA, Gillin JC. Sleep and psychiatric disorders. A meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(8):651-670.

- Coble P, Foster FG, Kupfer DJ. Electroencephalographic sleep diagnosis of primary depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33(9):1124-1127.

- Armitage R. The Sleep of Depression – A Review of EEG Findings and Factors Influencing the Sleep of Depressed Patients. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2007;38(2):97–118.

- Mendlewicz J, Kerkhofs M. Sleep electroencephalography in depressive illness. A collaborative study by the World Health Organization. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:505-509.

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Hoch CC, Yeager AL, Kupfer DJ. Quantification of subjective sleep quality in healthy elderly men and women using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [published correction appears in Sleep 1992 Feb;15(1):83]. Sleep. 1991;14(4):331-338.

- Kupfer DJ. Long-term treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52 Supl:28-34.

- Manber R, Buysse DJ, Edinger J, et al. Efficacy of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Combined with Antidepressant Pharmacotherapy in Patients With Comorbid Depression and Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(10):e1316-e1323.

- Wilson S, Argyropoulos S. Antidepressants and sleep: a qualitative review of the literature. Drugs. 2005;65(7):927-947.

- Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, Cooke M, Denberg TD; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Management of Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(2):125-133.

- Buysse DJ, Germain A, Moul DE, et al. Efficacy of brief behavioral treatment for chronic insomnia in older adults [published correction appears in JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 1;179(8):1152]. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(10):887-895.

- Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, San Pedro-Salcedo MG, Kuo TF, Kalista T. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep. 2008;31(4):489-495.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

The influence of spirituality and resilience on suicide risk in Romanian patients with depression

Suicide is a globally widespread phenomenon, with approximately 700,000 people dying from suicide each year. According to World Health Organization...

Contemporary psychotherapy between time and event. A psychoanalytical perspective (II)

There is, of course, a progression in the degree of generality of concepts. As we know so well, the more general a law, the more valuable it will b...

The link between alcohol use disorders and suicidal behavior

According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2019), approximately 800,000 people die each year by committing suicide(1). Alcohol has always occ...

Psychiatric comorbidities and social factors influencing delayed diagnosis for male cancer patients

The incidence and mortality of male cancer patients have higher rates than in women (512.1 versus 418.5, respectively 204 versus 143.4). The oncolo...